Much has been said about Iran taking advantage of the instability in the Arab world to increase tensions. Sending two ships through the Suez Canal to a Syrian port, at this time, signalled Iran’s desire to project Iranian power far beyond its neighbourhood.

But such stunts miss the point. The more important consequences of the Arab people’s rebellion are its impact on the Iranian people. There are at least four connections between Iran and the Arab sandstorm currently sweeping through the region. First, Arab republics have proven far more vulnerable than Arab monarchies. Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, and Libya, all experiencing intense change, are post-monarchies. By contrast, Morocco, Jordan, the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council, comprising Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE, Kuwait and Oman, are ruled by royal families/monarchs. Their kings and emirs can fire the government, move gingerly toward a constitutional monarchy like the United Kingdom and, perhaps, survive this Arab sandstorm.

Is the Islamic Republic of Iran more like a vulnerable republic or a durable monarchy? Until the summer of 2009, the supreme leader under the velayat faqih that Ayatollah Khomeini introduced in 1979, reigned like a monarch above the fray. That fiction of being removed from government disappeared when Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei supported the incumbent President Ahmadinejad in a blatantly partial manner following the disputed election of June 2009. Khamenei became the target of the demonstrators of Tehran chanting "down with the dictator". Iran appeared more and more like an Egypt or Libya than an Arab monarchy, making its leaders vulnerable to an uprising from the people.

Second, the mass demonstrations in Egypt’s Tahrir Square did not call for a return to Arab nationalism under a dictator like Gamal Abdel Nasser. Indeed, the only remaining Nasserites, President Saleh of Yemen and Muammar el-Gaddafi of Libya, are nearing their end. Pan-Arab nationalism, which did little to help the people of the Middle East and much to cause decades of wars, is not likely to re-emerge in Egypt or elsewhere in the region.

Nor is Tahrir Square a desire to substitute autocracy with another form of dictatorship under Islam. Looking at Egypt’s revolution optimistically, the young, connected and cosmopolitan people of Egypt are not likely to stand by and allow a Sunni form of Khomeiniism hijack their revolution, no matter how organized the Muslim Brotherhood.

In that sense, Tahrir Square can be viewed as both an inspiration to and an acknowledgment of the young Iranians who demonstrated in their cities 18 months earlier. Those young Iranians also want political empowerment and are fed up with a president who abuses his powers and a supreme leader who is unaccountable.

Third, the Arab populations no longer accept the notion that their countries can be run by families like private companies. The Gaddafi family and Tunisia’s Ben Ali and his in-laws, the Trabelsis, managed their countries like ATM machines. Syria is especially vulnerable because no Arab family exhibits more mafia tendencies and business monopolisation than the Assads and their in-laws, the Mahkloufs.

Is Iran also run by greedy families? Analysts have cited several instances of enrichment by family members of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Mojtaba Khamenei, the son of the supreme leader, is not unlike Gamal Mubarak of Egypt. The more telling similarity to the Arab dictators is the symbiotic relationship between regime leaders and Iranian revolutionary guard figures in carving up increasing oil revenues for their mutual benefit rather than for the people of Iran, who find not jobs but a crumbling infrastructure all around them. How much longer will that be tolerated?

Finally, Libya offers a fourth lesson on the wisdom of shooting unarmed demonstrators. The regime in Tehran should be very worried if Gaddafi falls because the lesson of Tripoli will be that the egregious human rights violations of Gaddafi against his own people have failed to intimidate or stop the protest movement. On the contrary, the killing of hundreds of Libyans in funeral marches and elsewhere in the streets of Libyan cities have spurred on the protestors and repulsed the entire world. Even Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez says he does not agree with all of Gaddafi’s actions. It is ironic that the Iranian government condemns Gaddafi. His downfall may remove the efficacy of the one card that the Iranian regime still holds, and that is a monopoly on force, and the willingness to use it against any popular insurgency.

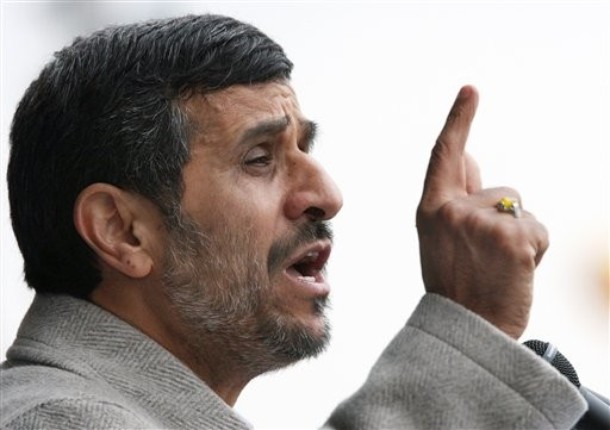

Never before has so much been at stake in the Middle East. If the Iranian people push their regime from power, Iran may become a model of democracy for the region. But if this regime in Iran survives the internal clamouring of the people for accountability and reform, then Ahmadinejad and company will distract attention from their own domestic vulnerability on human rights and economic mismanagement by trying to poison the coming elections in Egypt and other Arab countries. Ahmadinejad is no fool. He will change the new Mideast narrative from being against corruption, repression and unaccountability, to the more familiar anti-occupation, anti-American and anti-Israel narrative, which still resonates powerfully in the Arab world.

Jonathan Paris is a Middle East analyst and Nonresident Senior Fellow with the South Asia Center of the Atlantic Council, and author of "Prospects for Iran" published in 2011 by Legatum Institute, a London-based policy research center. This article originally appeared on Standpoint Magazine’s website. Photo credit: AP Photo.

Image: ahmadinejadgesture.jpg