Obama administration faces uphill task with critics in Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Congress

Now that world powers have struck a deal with Iran limiting Tehran’s nuclear program in return for phased sanctions relief, the Obama administration faces the uphill task of selling the agreement to US lawmakers as well as friends and allies in the Middle East.

Members of Congress—mostly Republicans—along with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Saudi officials, and Iranian hardliners have been ardent critics of such a deal.

Congress, however, is unlikely to be able to prevent the accord from going forward, said Clifford Kupchan, Chairman of the Eurasia Group.

“I don’t think Congress can, or will, bring this deal down,” Kupchan said April 3 at a discussion hosted by the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Citing his conversations with Republicans in Congress, Kupchan said: “They correctly don’t think that they have the votes to override a veto of a bill that would bring down the deal. If the President gets a deal, it sticks.”

{soundcloud}https://soundcloud.com/atlanticcouncil/framework-for-a-comprehensive-nuclear-agreement-with-iran{/soundcloud}

Among other things, the so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action announced April 2 in Lausanne, Switzerland, increases the time Iran needs to develop enough highly enriched uranium to build a bomb to at least one year by shutting off the main pathways for Iran to achieve this goal.

Under the deal, inspectors from the United Nations’ watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), will regularly inspect all known nuclear facilities in Iran as well as any suspicious sites.

Iran’s compliance will be rewarded with the phased removal of US, European, and UN Security Council sanctions enacted in response to Iran’s nuclear program.

Kelsey Davenport, Director for Nonproliferation Policy at the Arms Control Association, said the deal is in line with what the White House had promised.

“From a nonproliferation point, I think this is a strong groundwork,” she said.

Congress, however, will still remain a significant obstacle, she said, citing legislation by Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-TN) that would require congressional review of an agreement.

“The Obama administration needs to focus its energy on Congress, explaining the parameters of a deal and then encouraging Congress to wait until after June 30 and see if an agreement is reached,” she said.

Congress could then require the President to certify that Iran is keeping its end of the bargain, she added.

Kupchan said the White House has been “overly resistant to a congressional role.”

He said it should have answers to questions on what he described as the “ten-year problem.” These include: What happens after the one-year breakout time expires in ten years; and can 1,000 centrifuges that will stay operative at the Fordow facility eventually be replaced with more advanced centrifuges?

This is “not a pretty deal” and “substantive gaps” concerning how and when sanctions will be lifted remain between the two sides, said Kupchan, yet “it meets the basic structure of a deal that curbs Iran’s access to a nuclear weapon.”

Not everyone is convinced.

Netanyahu called the agreement a “grave danger” that will “threaten the very survival” of Israel. However, there may be only so much he can do to oppose the deal.

Netanyahu is under domestic pressure in Israel because of the damage he has done to the US-Israeli relationship, Kupchan said, noting that the Prime Minister “has real constraints within Israeli politics to do something.”

The Obama administration may face an even bigger obstacle selling the deal in Riyadh. In a sign that he recognizes that challenge, Obama briefed Saudi King Salman on the terms of the deal with Iran prior to publicly discussing it April 2. The king later gave it a cautious nod, saying he hoped it would strengthen regional security.

In Riyadh, “the degree of anti-Iranian invective I heard dwarfed anything I have ever heard in Israel,” said Kupchan. “The administration faces a very tough challenge.”

The process of reaching a nuclear deal, which included marathon meetings around the world that often stretched into the early hours of the morning, has helped forge close working and personal relationships between US and Iranian officials.

“Whatever you think of the deal… it is very clear that what was agreed to yesterday and the process over the last two years has represented a tremendous change in the dynamics between our two countries,” said John Limbert, a professor of Middle Eastern studies at the US Naval Academy and former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Iran.

Despite that breakthrough, the US-Iran bilateral relationship is unlikely to be radically transformed anytime soon.

“The disagreements are not going to go away,” said Limbert, a former official at the US Embassy in Tehran who was held captive during the 1979 hostage crisis. “But now we have something which we haven’t had in over three decades, which is the ability to talk about issues we both care about.”

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s 2013 election raised hopes for change in Iran. However, Internet freedoms and the state of human rights—particularly women’s rights—have deteriorated. US journalist Jason Rezaian has been held in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison for more than eight months, while two opposition leaders and former presidential candidates—Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi—remain under house arrest.

“Rouhani has been very weak on everything but the nuclear issue,” said Kupchan. “If there is a final deal, his political clout is going to rise very significantly. That guarantees nothing, but makes it more likely that we will see slow, hard-fought progress in other areas that has so far been stifled by the hardliners.”

Barbara Slavin, Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, said one of the reasons Iran’s leaders had initially been reluctant to pursue a nuclear deal was that they worried the Iranian people would ask for more.

Now, she said, Iran’s stock market is likely to go up; its currency, the rial, will strengthen; and expatriate Iranians will look at investment opportunities back home.

“Psychologically, this is a huge shot in the arm for the Iranian people. This is not just about centrifuges and heavy water reactors, this is about human beings and about a country with an amazing potential that has really been squelched for all these years,” said Slavin, who moderated the panel discussion.

Limbert, a member of the Atlantic Council’s Iran Task Force, warned that progress on the nuclear deal could be oversold.

Successive Iranian governments have blamed Western sanctions for the poor state of Iran’ economy, but many analysts point to mismanagement, said Limbert. “So what happen when the sanctions go and the economic problems are not solved?”

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

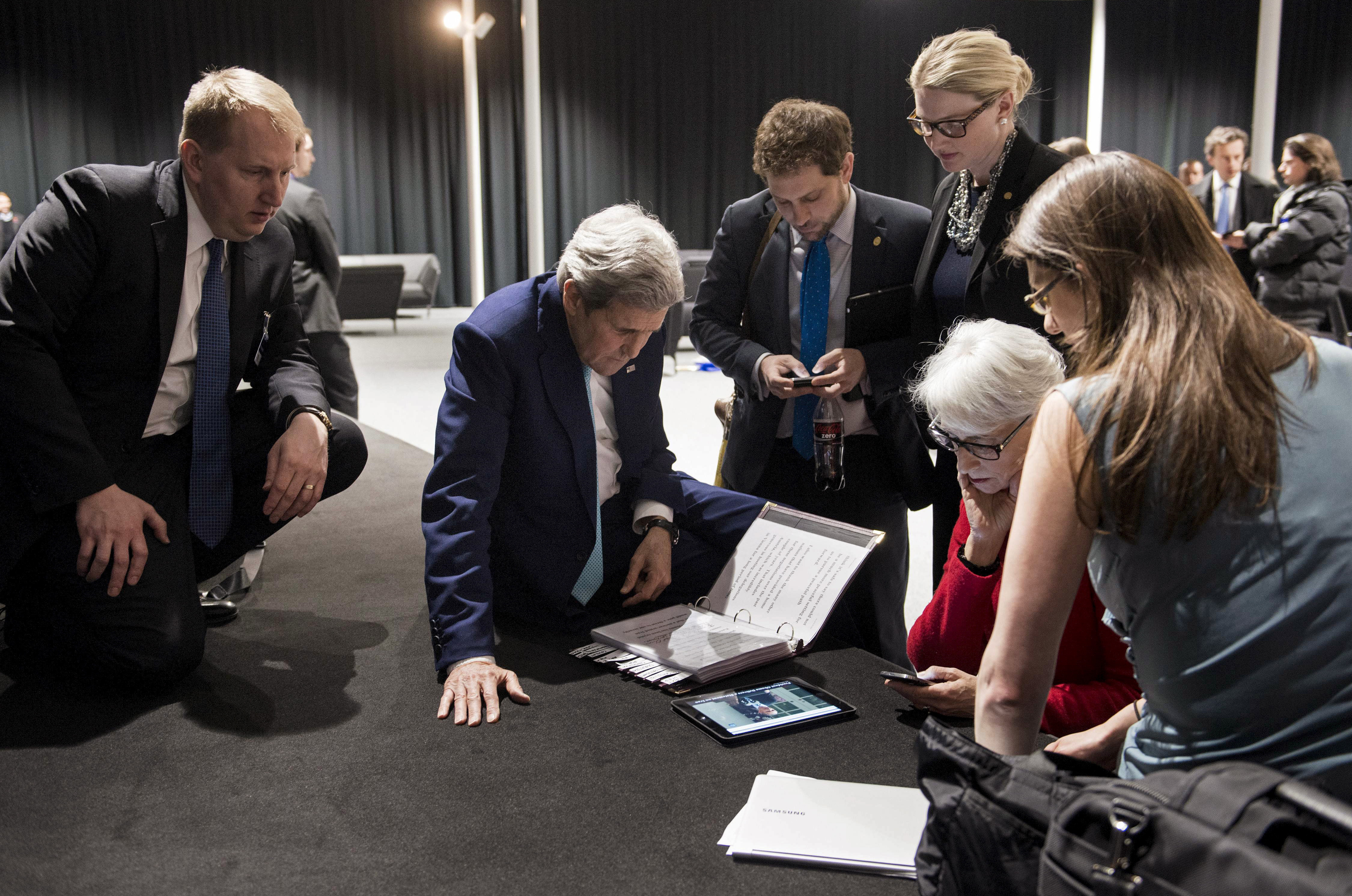

Image: US Secretary of State John F. Kerry (second from left), US Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Wendy Sherman (second from right), and staff watch in Lausanne, Switzerland, as US President Barack Obama makes a statement on a political agreement on Iran's nuclear program April 2. A preliminary nuclear deal between Iran and six world powers is a firm basis for a future accord that could end a 12-year nuclear standoff between Tehran and the West, though details must be worked out, Kerry said. (Reuters/Brendan Smialowski)