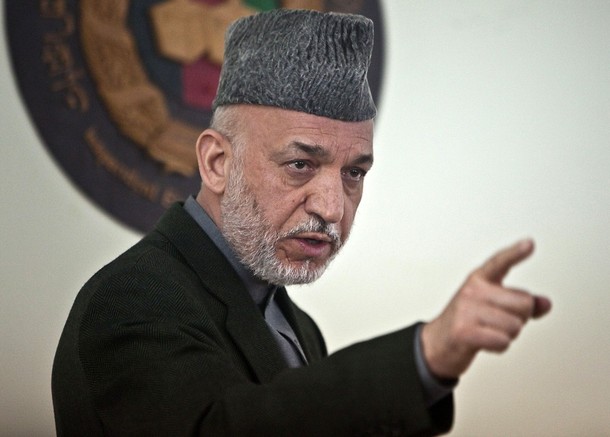

On April Fools Day, Afghan President Hamid Karzai lashed out at "foreigners" who have been criticizing his corrupt, inept government, leveling bizarre charges that the rampant fraud in the recent elections was perpetrated by UN officials, the European Union, and other non-Afghans. It was, alas, no joke.

In addition to bringing the retort from Peter Galbraith, the former UN official who was among those attacked by name in Karzai’s rant, that the president "is a bit unhinged" and "has a slim connection with reality," the remarks further draw into question Karzai’s ability to provide the political leadership that all observers consider critical to the success of the NATO mission in Afghanistan.

These fears were not much allayed by a 25-minute phone call from Karzai to Hillary Clinton trying to mend fences. His spokesman, Waheed Omer, claimed the Afghan leader had been misunderstood. "Obviously there is a difference of opinion on certain issues between Afghanistan and its international partners, but the president wanted the international community to pay attention to the concerns of the Afghan people and the Afghan government," he told Reuters.

While politically embarrassing, however, Karzai’s remarks were neither unprecedented nor, in perspective, surprising.

As Robert Haddick, the managing editor of Small Wars Journal, reminds us, "Karzai wasn’t shy about delivering a similar message in a November 2009 interview with PBS’s Newshour, whose audience includes the Washington establishment: "[T]he West is not here primarily for the sake of Afghanistan. It is here to fight the war on terror…. We were being killed by al Qaeda and the terrorists before Sept. 11 for years, tortured and killed; our villages were destroyed, and we were living a miserable life. The West didn’t care nor did they ever come."

The reason’s the same now as it was then: He’s maintaining a fragile grip on the leadership of his county and is seen by his detractors as too Western and too much a puppet of Washington. Further, as Damon Wilson, vice president and director of the Atlantic Council’s International Security Program puts it, "President Obama humiliated him" by publicly upbraiding him on Afghan soil in his recent visit.

Toughing It Out in Afghanistan co-authors Michael O’Hanlon and Hassina Sherjan, writing in this weekend’s WaPo, agree. While they say that "Karzai went too far" and his comments "were unfair and risked encouraging critics of the Afghanistan mission who want to portray foreign forces as unwelcome," they believe "his remarks were also a predictable result of American browbeating. Historically, negative treatment of the Afghan leader has produced these sorts of reactions."

Further, it’s smart politics for Karzai, who must be seen as his own man by his countrymen.

"Nationalism works," says Ross Wilson, a veteran diplomat and new director of the Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center at the Atlantic Council. Especially, I would add, if the target are outsiders seen as interlopers.

Time columnist Tony Karon agrees:

[B]izarre as his behavior may seem, there may be a method in Karzai’s madness. For one thing, he has begun denouncing the Western powers in his country because he knows he can — Karzai would have been cut adrift some time ago if there were any other viable alternative on whom the U.S. could pin its strategy. The wily president knows that the presence of foreign forces in his country is deeply unpopular, particularly when civilians are killed in the course of NATO military operations. Karzai, moreover, is humiliated and shown to be powerless when his protestations over such operations are ignored by his Western patrons. So, while he may have been installed by a U.S.-led invasion, if Karzai is to survive the departure of Western forces, he will have to reinvent himself as a national leader with an independent power base. He’s obviously determined not to go the way of Najibullah, the former Soviet-backed leader executed by the Taliban seven years after the Red Army withdrew. So, from Karzai’s point of view, he’s pushing back against the U.S. not only because he can, but also because he must if he is to survive politically.

Haddick adds:

The White House needs the American public, not to mention its soldiers, to believe in the Afghan mission. Publicly quarreling with and disparaging Karzai and his government can quickly shatter that belief. Similarly, Karzai’s open distrust of America’s motives is no doubt a boost to the Taliban’s recruiting.

U.S. officials think they have valid complaints about the performance of Karzai and his government. It must seem paradoxical to many of those officials that their leverage over Karzai declined with each increment of U.S. escalation. They’d better quickly accept that paradox if they wish to avoid a debacle.

Aside from the domestic politics angle, South Asia scholar Vikash Yadav sees a legitimate policy dispute:

Washington and its "partner" in Kabul are simultaneously pursuing different strategies to try to bring the war in Afghanistan to a conclusion. While the US has opted to pursue a "whack-a-mole" military strategy across Southern Afghanistan that drives the Taliban from one district only to have them pop up in the next one, the Karzai regime is moving forward with its reconciliation strategy. In essence, the Americans have foregrounded a military strategy while the Karzai regime (with some support from the UN) is promoting a political strategy.

If so, then Karzai genuinely needs to make nice with his adversaries to prepare the ground for a deal.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. Photo credit: Reuters Pictures.

Image: hamid-karzai-iec-speech-2010.jpg