The uproar surrounding Ecuador’s grant of political asylum to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has obscured huge inconsistencies. Only by examining them can we understand what is truly at stake in the case.

For starters, a government with a dubious record on freedom in general, and press freedom in particular, is waving the flag of rule of law and respect for freedom of expression while casting doubt on Sweden, a country that leads the world in its respect for due process and international law.

That is not all. The head of Assange’s legal team, Baltasar Garzón, has been a fervid champion of the narrowest interpretation of political asylum, gaining international standing with his successful petition to extradite Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. Now, however, he is advocating exactly the opposite.

Assange’s rejection of extradition to Sweden for questioning on allegations of sexual assault is based on the supposed interference in the case by the United States. But no such interference has materialized in any way, shape, or form. So, while Ecuador waves the banner of anti-colonialism against Britain, the bottom line is that Assange, Garzón, and Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa are simply playing the old “blame America” card to evade a properly issued European Arrest Warrant (EAW), upheld by the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court.

Beyond the facts of the Assange case, its significance consists in the current rise of a brand of populism that cloaks itself in the rule of law while invariably undermining the law’s reach and enforcement. Ecuador’s stance on the case has been echoed by other members of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), including Cuba and Venezuela. And yet, according to Reporters without Borders (RWB), Ecuador ranked 104th out of 179 countries for press freedom in 2011-2012. Similarly, the 2012 Freedom House Index (FHI) classifies Ecuador as “partly free,” and on a declining trend.

It is also worth noting that Venezuela, ALBA’s leading member, ranks no better (117th on the RWB scale and also “partly free” on the 2012 FHI). In marked contrast, Sweden leads the RWB’s rankings, and is one of only two states to receive excellent scores on both political and civil liberties from Freedom House.

Beyond the numbers, RWB and Freedom House have noted a decline in freedom in Ecuador recently, pointing to Correa’s persistent campaign against media critics, his government’s use of state resources to influence the outcome of a referendum, and the reorganization of the judiciary in blatant violation of constitutional provisions. Meanwhile, a recent report on Venezuela by the International Crisis Group notes unfair conditions established in the run-up to the upcoming presidential election and the absence of a level playing field for the media.

Correa’s recent statements embody these contradictions. As recently as May 2012, he pontificated that “[t]he governments trying to do something for the majority of the people are persecuted by journalists, who think that by having a pen and a microphone they can direct even their resentment against you. They often insult and slander out of sheer dislike. These are mass media serving someone’s private interests.”

And yet this statement came in an exchange with none other than Assange, the self-proclaimed crusader for freedom of expression, during a recent TV show aired on a Russian channel controlled by President Vladimir Putin’s government.

Unfortunately, the sham rule of law pushed by Assange, Correa, and other populists is gaining adherents in today’s globalized world. This is dangerous, because their signature approach is the selective and inconsistent application of legal or quasi-legal principles and precepts, which is the very opposite of the rule of law’s dependence on generality and predictability. By distorting reality and impugning the Swedish legal system – a standard-bearer for legal certainty, fairness, and professionalism – the champions of this subversion are undermining the foundations of an international system that serves as a bulwark against totalitarian impulses.

Yet the strangest aspect of the Assange affair is the deafening silence on the part of those actors and institutions whose existence and legitimacy emanates from the completeness of the rule of law. The European Union’s silence is perhaps the most disturbing. The official Web site of the European External Action Service includes a plethora of pronouncements and condemnations on issues ranging from Syria to Madagascar to Texas, but a keyword search of “Assange” returns a single entry from April 2012 on Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s reaction to WikiLeaks.

Indeed, no EU leader – not the verbose European Commission president, José Manuel Barroso, the ever-grey president of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, or the cautious High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Catherine Ashton – has seen fit to counter unfounded attacks on two EU members. Nor have they bothered to defend a much-heralded cornerstone instrument of the Union – the EAW, under which the UK first detained Assange.

How is it that the EU, much criticized for its proclivity for declarations and statements, is silent on an issue where its voice not only would make sense, but also could make a difference? Whatever the reason, it is time that the Union’s leadership reverse course and speak out, loudly and clearly, taking the initiative that other international leaders and organizations would, one hopes, heed and emulate.

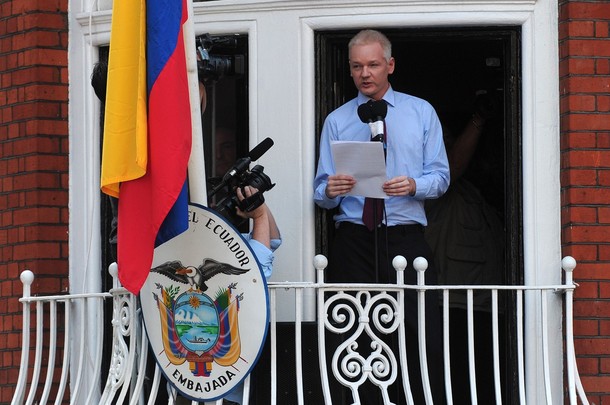

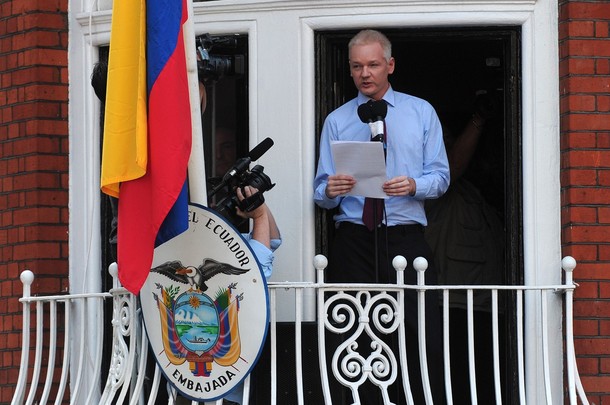

Ana Palacio, a board director at the Atlantic Council, is a former foreign minister of Spain. This piece originally appeared on Project Syndicate. Photo Credit: Getty Images

Image: julian%20assange%20ecuador%20embassy.jpg