A familiar story has been unfolding in Nairobi, Kenya, in recent days. Demonstrations against planned tax increases got out of hand, fueled by a heavy-handed police and military presence. Protesters stormed Kenya’s parliament, forcing President William Ruto to withdraw a tax bill supported by an International Monetary Fund (IMF) team just a few days earlier. Commentators and social media posts reveled in blaming the chaos on IMF-induced austerity, accusing the lender of yet again imposing a “colonial” agenda on the Kenyan population.

One of the IMF’s tasks is indeed to deflect some of the political blame from a government that has committed to fiscal adjustment measures and faces public opposition. Even after the bill was withdrawn, however, public anger has yet to subside, fueled by killings of demonstrators and accusations of corruption and misuse of public money.

The truth is, of course, that Kenya’s decline into fiscal trouble has been entirely predictable, led by the ambitions of past leaders who followed the path of easy money. Especially during the mid-2010s, under President Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenya was looking for ways to leverage its “frontier market” status into higher growth via debt-financed investments and infrastructure projects. As a result, within a decade, Kenya’s public debt ratio almost doubled from 41 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014 to a projected 78 percent of GDP in 2024.

One prominent creditor has been China’s Export-Import Bank, which provided Kenya with $3.2 billion to build a Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) between Nairobi and the port of Mombasa—a project that has been criticized because of its weak governance and high cost but, according to recent reports, will be extended to Kenya’s western border with Uganda.

Although public investment does have an important role in raising a country’s economic fortunes, Kenyans are still waiting to see the social returns of the debt-financed investment spree. GDP growth has hovered around 5 percent since the mid-2000s, real GDP per capita has stagnated in recent years, and the poverty rate (at just below 40 percent) remains above pre-COVID-19 levels. It is no wonder that the fiscal belt-tightening now required to arrest a further run-up of public debt has met with resistance, amid legitimate questions about who benefited from the loans that ordinary Kenyans now have to repay.

Ruto, in office since 2022, carries his share of responsibility for the fiscal sins of the past, having been vice president in the previous administration and a proponent of the Chinese railway loan. His government is also dealing with droughts and the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, which hit Kenya and other frontier markets particularly hard, including through spillover effects from global inflation and higher interest rates. Being caught out in a weak fiscal position and facing eventual default, Kenya turned to the IMF in 2021 to help stabilize its finances, including a “multi-year fiscal consolidation effort centered on raising tax revenues and tightly controlling spending.”

The government did reasonably well under this program, which originally foresaw a steady pace of fiscal adjustment (at about 1 percentage point of GDP per year over five years) and allowed for measures to absorb its social impact. Both the primary fiscal deficit and the trade balance improved, and the shilling unwound much of its decline vis-à-vis the US dollar as Kenya surprised markets by repaying a two-billion-dollar Eurobond last month. Moreover, the program unlocked a considerable amount of concessional multilateral financing, including from the World Bank.

But the country remains in a financial hole from which it will be very difficult to climb out. One problem is that higher interest rates keep adding to Kenya’s debt dynamics, as illustrated by the hefty 10 percent interest rate on a smaller Eurobond that Kenya issued in February to meet its June payment. Therefore, despite an improvement of the primary deficit broadly in line with program targets, Kenya’s public debt is still projected to increase this year.

While the government planned to continue on its programmed adjustment path, the latest package of measures—including tax measures to offset gradual revenue slippages over the years—appears to have been the political straw that broke the camel’s back. So, what are the alternatives available to the government now?

- First, “keep calm and carry on” may be the motto of the day. The government appears to be looking for spending measures to substitute for lost revenues, but this will not be viable in the long term. Expenditure compression has its own distributional (and political) consequences, and the overall fiscal adjustment strategy will need to be balanced across revenue and spending items.

- Second, with interest payments accounting for more than a quarter of total revenue, the Kenyan government may decide to seek a debt restructuring. This is not something the IMF could impose on Kenya, unless it judged that public debt was unsustainable. However, the government went to great lengths in the past to service its debt and retain access to financial markets. It would have been cynical on the part of IMF shareholders, who routinely call for strong ownership from program countries, to force Kenya into an unwanted debt operation—as long as there was still a realistic chance of avoiding it. This now looks less assured, and it may be the only avenue left for the government.

- Third, however, the Export-Import Bank of China is the biggest bilateral lender to Kenya, holding claims worth $6.5 billion, close to two thirds of all bilateral debt. China has a special responsibility to provide debt relief, given the history of corruption and questionable economic value of the SGR project it helped finance. Kenya would have to request a debt treatment under the Group of Twenty (G20) Common Framework, which has recently become more efficient in dealing with problem cases. However, bilateral debt negotiations could still take a long time to resolve, and Kenya would risk being cut off from external financing for a considerable period.

As the government needs to chart a fresh course in this difficult environment, it is also very likely that supporters in the West will call for more money and fewer fiscal adjustment as the solution to Kenya’s problems. The Nairobi-Washington Vision, formulated during Ruto’s state visit to the United States in May, has also called for increased financial support for developing countries. The question is, where should this money come from?

- First, anyone who has looked at a financing needs table of an IMF program (for example, see Table Six here) understands that spending can either be financed by revenues, grants, or borrowing. Since grants don’t carry any interest or repayment burden, they would be ideal for a country in Kenya’s situation. But taxpayers in rich countries have shown less and less inclination to finance development aid, let alone through direct transfers or outright debt relief for poorer countries.

- Second, the IMF and other multilateral institutions have raised funds and mobilized special drawing rights (SDRs) in recent years to subsidize interest rates paid by poorer member countries, and Kenya is already benefiting from this effort. However, there are limits to this approach. Subsidies have to be either financed from donor countries’ budgets (with less and less political support) or they are generated from richer countries’ SDR holdings.

- Third, SDR-based lending works only to a limited extent. SDRs derive their value from their status as foreign exchange reserves and being exchangeable for dollars and other hard currencies held by central banks in wealthy countries. Any overuse or exposure to default risk (for example, from rising public debt in recipient countries) could compromise their reserve-asset status, which would impact both the IMF’s financing model and its capacity to lend to countries in distress.

- Fourth, could the IMF and World Bank provide larger loans? The two institutions regularly review the amounts that countries can access under various conditions. Ceilings have gone up over time, but shareholders (who carry the ultimate risk) generally require that larger loans come with stricter macroeconomic conditionality, an approach that would presumably have triggered a similar outcome for Kenya. Moreover, multilateral loans already account for more than a quarter of Kenya’s public debt. Since these loans cannot be restructured, private creditors might be more hesitant to invest in the country, because any future debt operation might need to be deeper than in similar countries with a smaller share of multilateral debt.

To sum up, Kenya’s predicament is largely homemade, albeit with help from willing external lenders. The COVID-19 crisis exacerbated a lack of fiscal discipline, eventually forcing the country to adopt a stabilization program. While meeting with some initial success, recent events have made it clear that the government’s adjustment strategy needs to change, putting a possible debt operation on the table. The IMF did its best to support an initially credible effort by the government, but it must also ask itself what could have been done to prevent the sharp increase in public debt that is at the heart of Kenya’s problems today.

Martin Mühleisen is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and a former IMF official with decades-long experience in economic crisis management and financial diplomacy.

Further reading

Wed, May 22, 2024

Ruto’s state visit to the White House is overdue. So is Biden’s visit to Africa.

New Atlanticist By

Just as important as the Kenyan president’s visit to the United States this week is how soon the US president visits Nairobi in return.

Tue, Apr 2, 2024

Why Africans hold the future of global democracy in their hands

AfricaSource By Rama Yade

By the end of 2024, the face of political Africa will—theoretically—no longer be the same. With nineteen elections scheduled this year, the continent will see presidents leave who were elected more than ten years ago (in Senegal and Ghana), uncertain civilian transitions (in Chad, Mali, and Burkina Faso), high-stakes elections (as in South Africa), and strongmen hanging on (in Tunisia and Rwanda).

Mon, Jul 1, 2024

From greenfield projects to green supply chains: Critical minerals in Africa as an investment challenge

Report By Aubrey Hruby

This report provides a snapshot of Africa’s mineral wealth and mining industries, draws out the similarities between the mining and infrastructure investment attraction challenges, describes the competitive landscape African nations find themselves in, and makes innovative recommendations—namely to the US government—to rapidly accelerate investment in sustainable mining industries in African markets.

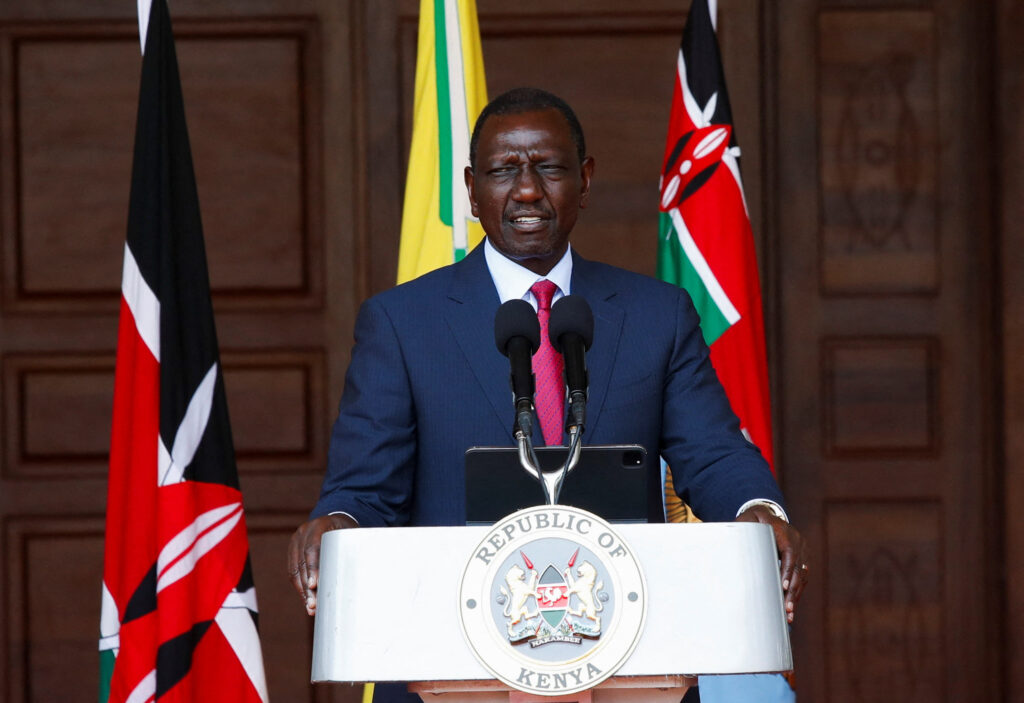

Image: Kenya's President William Ruto speaks at a press conference where he announced spending cuts in government after protests against Kenya's proposed finance bill 2024/2025, in Nairobi, Kenya, July 5, 2024. REUTERS/Monicah Mwangi