Second-guessing is a Washington pastime. Critics are chastising the Obama administration for "turning on a dime" and, after much reluctance to become involved in Libya, moving too quickly to use force against the Gaddafi regime. They argue that the administration’s about-face last Tuesday night has resulted in a lack of clarity in the mission, minimal consultation with Congress, failure to bring along public opinion, and incoherence in military command and control of the operation.

While the administration needs to better address these issues, two key factors justify the administration’s decision-making in the lead-up to the start of the military campaign: the unexpected rallying of the international community to stop Gaddafi’s assault on civilians and the imminent prospect of a humanitarian catastrophe.

Since taking office, President Obama has been clear that under his watch the United States will act, especially militarily, in tandem with allies and partners, and only when those actions enjoy broad-based support and legitimacy. In Libya, this approach translated into administration requirements that any action entail substantial participation by other nations and be sanctioned by the UN Security Council (UNSC). To most observers, the prospect of meeting those requirements was minimal.

Unusually, in this crisis, our allies were out in front. France and the United Kingdom made clear their willingness to make major military contributions to any coalition effort to enforce a no-fly zone. Other allies signaled they would step forward as well; subsequent to the UN vote, Denmark, Norway, Canada, Italy, Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands have indeed committed forces. Furthermore, French, British, and U.S. diplomacy paved the way for likely contributions from Arab states, including military forces from Qatar and possibly UAE and other types of support from Egypt, Tunisia, Jordan, and Morocco. By the evening of March 15, when the president reversed course, it had become apparent that the United States would neither be faced with acting alone nor with bearing the overwhelming brunt of the operation.

Furthermore, remarkable and swift diplomacy reversed a situation in which the Security Council went from being a sure block on military action to an enabler. Days before the successful vote, seasoned diplomats bet heavily against meeting NATO nations’ precondition of UNSC authorization. The composition of the Council only reinforced a sense of intransigence. Traditional skeptics and permanent Council members China and Russia were joined by the other BRICs—India and Brazil—both traditionally cool to military interventions. Three African nations on the Council—Gabon, Nigeria, and South Africa—were expected to reflect general African resistance (and African Union silence), given Kaddafi’s record of showering the continent with economic support in exchange for political backing. Finally, Lebanon, now with Hezbollah in its government leadership, seemed an unlikely supporter of military action.

Yet the remarkable outcome of the Arab League meeting on March 12 to support "humanitarian intervention" to defend civilians in Libya dramatically shifted the center of diplomatic gravity in New York. Secretary Clinton’s assessment of international support also shifted as she listened to her G8 partners in Paris, met a leading Libyan opposition figure, and absorbed lessons for U.S. policy during visits to Egypt and Tunisia.

No longer were British and French diplomats pushing a rock up a hill alone in New York. Joined by the Americans on March 16, and fueled by the Arab League statement and Gaddafi’s commitment to show "no mercy," the coalition in support of action grew. Not only were supporters able to convince skeptics to abstain rather than veto a resolution, they were also able to broaden the resolution’s language to authorize "all necessary measures." Once the administration shifted from observer to leader, it embraced the idea of "if you do it, do it right." Administration officials accurately judged a no-fly-zone in and of itself would be woefully insufficient to reverse Gaddafi’s tactics, while only implicating us further in the crisis without the tools to impact the outcome. The result was a stunning 10-0 vote in the Security Council for a surprisingly robust resolution only one day after the U.S. shifted its position. Such diplomatic victories don’t just happen.

At the same time, Gaddafi’s forces had been regrouping and were advancing on rebellious cities. Most notably his forces were steadily regaining territory in the east. By Saturday, March 19, Gaddafi’s forces were moving on Benghazi as world leaders were gathering in Paris to provide diplomatic muscle and broader political cover to the coalition forces gathering in the region. The administration and its coalition partners were faced with the prospect of an imminent massacre in Benghazi and the consolidation of Gaddafi’s control over the country rendering the UNSC vote useless.

In this context, French fighter jets initiated military action followed by U.S. and British missile strikes. The immediate effect was to spare Benghazi’s population from Kaddafi’s ruthless vengeance. If the coalition had delayed military action, even by just 24 hours, we would likely have witnessed the worst civilian atrocities of this conflict.

The military intervention would have benefited from more time to better align the coalition around a clear mission, to consult Congress, and to rally public opinion. But any further delay would likely have led to the humiliation of the international community as Gaddafi delivered on his promise to show "no mercy" to those resisting his rule. Having secured the diplomatic backing many thought impossible, the coalition could not afford to sit back and watch a slaughter of civilians in Benghazi and the routing of the rebels. Furthermore, a victorious but wounded Gaddafi would be sorely tempted to return to his old playbook of supporting terror against the West. Moving quickly from a UNSC vote on Thursday, March 17 to military action on Saturday, March 19, was the only viable course to achieve the objective of the UNSC resolution.

The administration and its coalition partners acted once they had the international backing to preventcatastrophe. They demonstrated that they learned the lessons of Bosnia, Kosovo, and Rwanda. In some cases, waiting too long to engage only means you pay a higher price when you are forced to intervene later.

Now the administration needs to work with its partners to sort key details, including most urgently agreeing to unified NATO command and control of the military campaign. But I’d rather the administration have to contend with criticism of its management of the conflict rather than live with the legacy of sitting by as Benghazi burned.

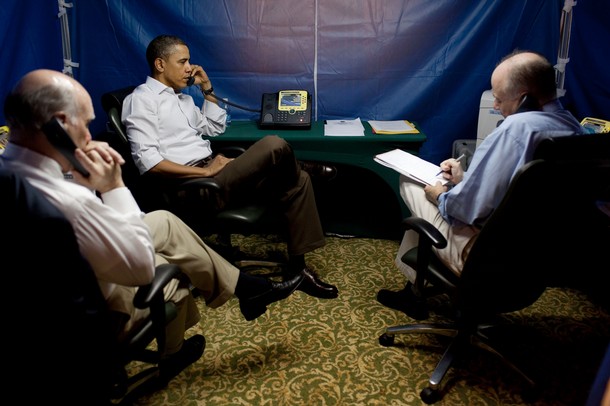

Damon Wilson is Executive Vice President and Director of the International Security Program at the Atlantic Council. Photo credit: Getty Images.

Image: obama-libya-decision.jpg