German chancellor’s visit to Washington puts focus on US-German, US-European relationships, says Atlantic Council’s Fran Burwell

German Chancellor Angela Merkel faces a tough re-election battle in September and a meeting with US President Donald J. Trump is perhaps not the best way for her to burnish her credentials with the German electorate. The fact that she is making the trip across the Atlantic is an indicator of her determination to shore up the US-German and US-European relationships that have been buffeted by often controversial rhetoric from Trump.

“If she were looking at this from a purely electoral calculation, she may not have even done this visit because no one in Germany wants to see her necessarily being close to President Trump,” said Fran Burwell, a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Making the point that the visit is more about the US-German and the US-European relationships, she added: “She is coming not only as the chancellor of Germany, but as the leader of Europe.”

Trump and Merkel got off to a rocky start in their relationship with the former accusing the chancellor of “ruining Germany” with her open-door policy for migrants fleeing war zones in the Middle East, and the latter criticizing Trump’s “America first” policy and his decision to order a temporary ban on immigrants from seven—subsequently six—Muslim-majority countries, as well as all refugees.

Merkel, Burwell said, is likely to keep the focus of her visit on assuring Trump that Germany is serious about increasing its defense spending in line with NATO’s target of two percent of the GDP for member states, ensuring Trump is on the same page as Europe’s leaders with regard to the threat posed by Russia, and emphasizing the positive nature of the US-German trade relationship. That last area was called into question by Trump’s senior advisor, Peter Navarro, who accused Germany of using a “grossly undervalued” euro to harm the US economy.

Burwell said that beyond rhetoric, Trump can take some concrete measures to shore up the transatlantic relationship. These include a clear commitment to NATO at the Alliance’s summit in Brussels this year, ditching his preference for bilateral over multilateral agreements and focusing instead on what is best for the United States (in this case, a trade deal with the EU), and refraining from taking sides in the Brexit negotiations.

Fran Burwell spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: Chancellor Merkel is visiting Washington at a time when the election campaign is heating up in Germany. To what extent is this trip aimed at a domestic audience and how do you expect this meeting to play out in Germany?

Burwell: Anytime someone like Chancellor Merkel goes abroad there is a domestic element, particularly now that we are in election year. Her announced opponent, Martin Schulz, is actually doing very well in the polls. Of course, we are a long way from the fall.

If she were looking at this from a purely electoral calculation, she may not have even done this visit because no one in Germany wants to see her necessarily being close to President Trump. That’s not going to be the politically popular thing to do. This is really much more about the US-German and the US-European relationship. She is coming not only as the chancellor of Germany, but as the leader of Europe.

I have no doubt that when [Merkel and Trump] do the press conference after their meeting, if the questions come up she will speak out strongly on issues such as climate change and others where most likely she won’t see eye to eye with President Trump.

But the priorities for this trip are much more focused on foreign policy and US-Germany and US-Europe relations. One, she is going to provide some assurances on German defense spending, which has been going up. Two, she wants to make sure that Trump hears her views on [Russian] President [Vladimir] Putin and she will push him, as some in the US administration have been pushing him, to understand why we are where we are with the Russians, why we have sanctions and why they are important to maintain. Germany and the chancellor in particular have been very firm on those sanctions.

They will also talk about US-German economic relations. Peter Navarro of the National Trade Council has implied that Germany is a currency manipulator. She will argue that this is not the case and that it is really much more important not to look at Germany’s trade surplus with us, but at the number of German companies that invest in the United States and have a lot of American employees.

I think she will also make the case that the European Union is a valuable institution and that the United States should not try to divide the EU; she will make the case that Brexit is not a precedent; and that if the United States wants to have trade negotiations with the Europeans that it is the EU that negotiates on behalf of the rest of the member states. She will make the case for the EU as a strong partner of the United States.

Of almost all the European leaders, she is the one that remains the most integrationist with the exception of those who actually work for the European institutions like [European Commission President Jean-Claude] Juncker and [European Council President Donald] Tusk.

Germany is also president of G20 this year. Trump has agreed to go to Hamburg in July. Merkel will want to get him on board for some of the G20 agenda. It will be tough as the German priorities include international cooperation on building a global economy. That language is very different from the “America First” language that we have been hearing from the president.

Q: Russia is expected to top the agenda of a Trump-Merkel summit. Chancellor Merkel has vast experience dealing with Russian President Vladimir Putin. What advice do you expect her to give Trump at time when the US president has stated that he wants better ties with Russia?

Burwell: She will probably make a very factual and rational case of what the Russians have done in Ukraine, as well as the concerns about Russian hacking; after all, the Bundestag was hacked in 2015. I suspect she will try and give some flavor of her conversations with President Putin because she, more than any other Western leader, is probably the one who has spoken to him the most. She has made clear that he has not always been very truthful with her. She will probably put that in front of the president.

Q: Why is it important for the United States to keep up the pressure of sanctions on Russia?

Burwell: It is important because we have some big companies, especially in the energy sector, which could disrupt the impact of the sanctions if they were not part of it. Moreover, US and European banking and financial institutions are intertwined. If our banks are operating on a different set of rules, without sanctions, and are able to deal with Russian banks that the Europeans are not, it doesn’t make for a very strong partnership.

It also has to do with leadership. The Russians, by annexing Crimea and instigating conflict in eastern Ukraine, have changed borders through the use of force for the first time since the Second World War. This is something that we and the Europeans together have made very clear is not appropriate. By giving up on the sanctions at this point what we say is that kind of behavior is permissible.

If we were to weaken the sanctions, we would find the Italians, possibly the French, depending on what happens in their elections, and some of the others waver. The consensus would be very difficult for the Europeans to maintain.

Chancellor Merkel herself has gone through an evolution on the sanctions. Germany was not enthusiastic about this at first. After all, German business has a lot of ties with Russia. But it seemed that as Chancellor Merkel began to negotiate with President Putin she got firmer and firmer as she became convinced that the Russians would not live up to what they had signed in Minsk without some kind of show of strength. To the Germans, sanctions are far preferable than any military response.

Q: While Vice President [Mike] Pence and Defense Secretary [Jim] Mattis issued reassuring statements while on recent visits to Europe, how helpful is that for the Europeans if it doesn’t come from President Trump?

Burwell: It is helpful. Particularly from Mattis in terms of NATO. Everyone is now focused on the NATO summit and trying to demonstrate the increases in European defense budgets that are underway. So, the statements [by Mattis] in Munich were helpful.

From Pence, it was a supportive statement, but not a very detailed statement, at least not in public. This past week, we had a very good meeting with European Commission Vice President Andrus Ansip and US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross on Privacy Shield, which is an important US-EU issue.

The problem is that European leaders don’t know if the statements of officials in the [US] administration, even cabinet officials, will be undercut by a tweet or a statement by the president, which is quite distinctly different. They don’t know what will be the impact of a US trade policy which seems to be focused on a bilateral rather than a multilateral trading system; what will be the role of [Trump advisor] Steve Bannon who has been extremely critical of the EU. We are in the early stages of guessing how the administration is going to be run and many of us in Washington have some of the same questions; for the Europeans, it is even more difficult.

Q: What, beyond rhetoric, should the Trump administration be doing to affirm US commitment to the transatlantic relationship?

Burwell: Number one is having a good NATO summit and making clear, even in advance of that, that there will be no deal with the Russians without consultation with our European allies.

Number two, cease the rhetoric about bilateral versus multilateral and just look for what is in US interests. I would make the case that working with the European Union, as opposed to all the member states separately, is in the interests of the United States. Our businesses want one big market with one set of rules, not twenty-eight little markets. Even though the EU can be extremely difficult to negotiate with, it is better than making deals with twenty-eight different countries. It is also true that when the EU acts together in the international arena, it has more impact. So, although there are all sorts of challenges, it is in our interests to act in partnership with the EU.

The United States should also not take sides in the Brexit negotiations. The British government will, probably by the end of [March], trigger Article 50 [to begin the process of leaving the EU]. The negotiations are going to get very, very difficult at times and very technical. We need to be supportive of both partners. We need to end up being friends with both of them after the divorce. We shouldn’t take sides, we should represent our own interests.

Q: What is the likelihood that the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) will become a reality?

Burwell: In the current form, I would say none. I do think that some form of a trade and investment accord with the European Union, our largest trading and investment partner, makes sense. Will it be under a different name, perhaps include different things, will it focus on investment and jobs? US-Europe trade is largely driven by investment. It makes a lot of sense to try and use negotiations not to create new rules and regulations, but to ease the burden of regulations in the transatlantic space. That is still a valuable undertaking and in US interests.

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

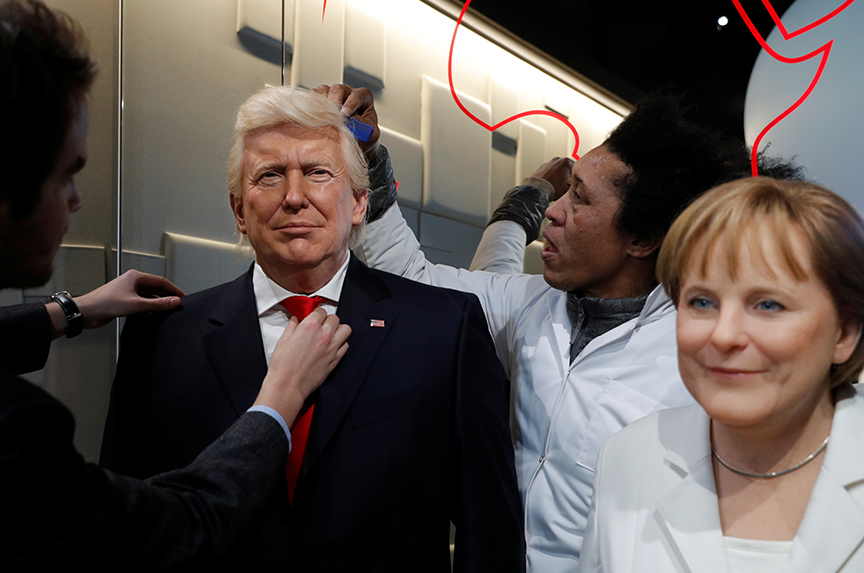

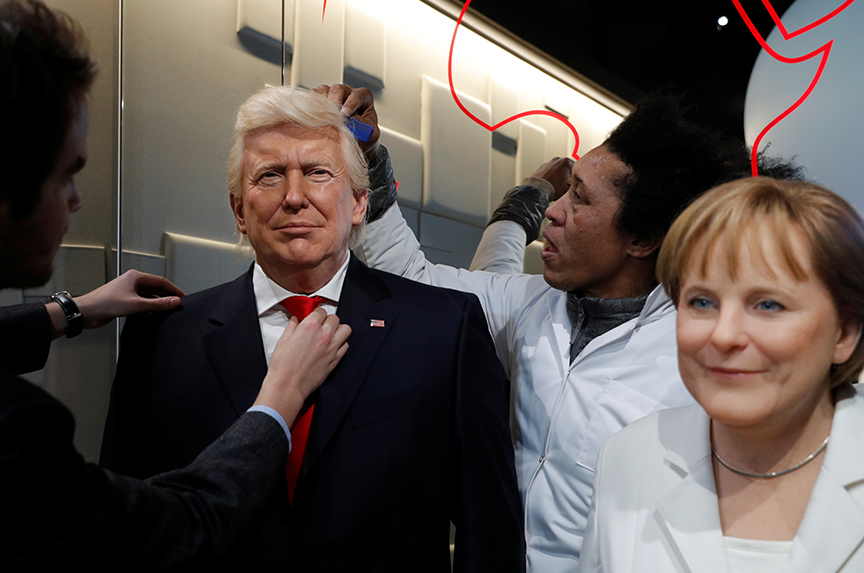

Image: Technicians adjusted a waxwork of then US President-elect Donald J. Trump, which was presented next to a waxwork of German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Musee Grevin in Paris on January 19. Trump will meet Merkel in Washington on March 17. (Reuters/Philippe Wojazer)