Who carried out the execution of three women prominent in the European branch of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in Paris on January 9 and what was their intended message are unclear.

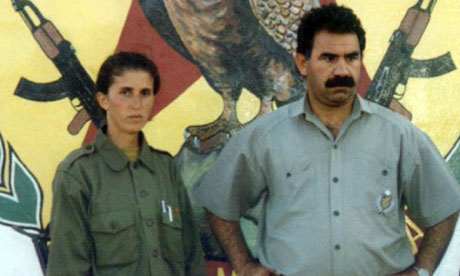

The dead included Sakine Cansız, a long-time senior figure in the organization, Fidan Doğan, the Paris representative of the pro-PKK Kurdistan National Congress, and Leyla Söylemez, a younger Kurdish activist. Regional players and pundits are already speculating: the assassinations were carried out by Turkey’s “Deep State;” they are opening shots in a war within the PKK over leadership and policy; or it might be Syria, Iran, or some other regional actor with an axe to grind. The motives ascribed depend on who was the actor and how conspiratorially inclined the pundit is. The obvious context is the unprecedented opening toward one another carried out in recent weeks by the Turkish government and jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan. For one reason or another, the perpetrators wanted to derail or at least skew that discussion, and they may well succeed.

Öcalan and the authorities in Ankara have danced with one another for some time. As early as 2005, Turkish intelligence engaged in quiet conversations with him and other PKK leaders, especially in Europe, to see whether and how some modus vivendi could end the violence. These sometimes showed promise, and some positive steps were taken, but ultimately each effort ran aground. In December, the authorities allowed Öcalan’s brother Mehmet to travel to his prison on Imralı Island in the Sea of Marmara, where the PKK leader has been held since 1999. Mehmet Öcalan subsequently announced that his brother believes “a new Kurdish initiative [by Turkey] could take place” to which, “if deep powers do not intervene,” the imprisoned PKK leader “will contribute.” Öcalan subsequently defused an anti-government hunger strike being staged by imprisoned Kurds accused of terrorism. On December 28, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan made public that Turkish intelligence had met with Öcalan directly days earlier–the first such public admission of high-level government conversations with the jailed PKK leader. In another unprecedented move, the government subsequently allowed two parliamentarians representing the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) to meet with Öcalan on Imralı and were reportedly told by the PKK leader that the era of armed struggle is over. These and other BDP figures traveled immediately after to northern Iraq and Europe to brief the PKK leadership abroad on Öcalan’s status and plans.

Turkish media exploded with reports that could not be confirmed and an immense amount of speculation about next steps and implications–so much that Turkish President Gül felt compelled to ask officials, pundits, and others to restrain themselves. The facts are known only to a handful of individuals who are not talking on the record, but most likely each side in the Turkey- Öcalan conversation has been feeling the other out. The opening is just that–an opening, not an agreement or even much of a negotiation. To say that much remains to be worked out is an understatement, but the symbolism was remarkable: for the first time ever, Öcalan was accepted as an interlocutor, the dialogue with him was made public, and Turks and Kurds had a reason to hope for an end to the decades-long fight that has sapped both communities, perhaps especially the country’s large Kurdish minority. Even the head of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, publicly offered the government some space in which to maneuver. Comments by Turkish Kurds were similarly hopeful, as were reactions from the Iraqi Kurds in Erbil.

Wherever Öcalan may be on the opening with the government, however sincerely he approaches the idea of some kind of deal, and however realistic it may be to think that a deal can be done, there surely is a segment of the PKK that is not impressed. These include career militants who know no other way of life. More worrisome are the Syrian and Iranian figures in the movement for whom negotiations with Turkish authorities mean nothing and who may, perhaps at the behest of Tehran and/or Damascus, very much want to continue the fight. There is also what one could euphemistically call the business side of the organization. PKK profits from illegal drug trafficking and sales, as well as gains from years of extortion and protection rackets are immense. How matters evolve in the coming days and weeks will, among other things, test Öcalan’s leadership and the prospects for completing any real negotiations that might take place.

The PKK dead in Paris were no saints; they associated themselves with brutal PKK tactics carried out over a long time against Turks and Kurds alike, and at least one of them likely played a role in the transfer of funds raised in Europe through drug sales and other illegal activities, as well as in more benign ways, to support those efforts. Their murders, however, make the fragile and barely started dialogue between Öcalan and the government even more tenuous and risk-fraught for all concerned.

Ross Wilson is the director of the Council’s Patriciu Eurasia Center.

Image: Sakine-Cansiz-with-Abdull-010.jpg