As one of the poorest countries in the world, Nepal needs a transparent and adequate pandemic response to both mitigate the effects of coronavirus and protect from a further increase in poverty. However, Nepal’s poor governance track record—characterized by inadequate leadership after the 2015 earthquake, a divided ruling party, corruption and mishandling of funds by the government, and questionable governance practices by the prime minister—not only puts the population at a disadvantage in weathering the pandemic, but it also may deal additional blows to the country’s health and economic wellbeing.

Nepal entered the pandemic era with several severe underlying crises, largely due to the government’s 2015 mishandling of earthquake disaster response, creating the conditions ripe for pandemic response failure in 2020. Today, 44 percent of healthcare facilities that were damaged in 2015 have yet to be reconstructed; over 70 percent of the population is involved in the informal economy, where they lack access to critical social safety nets; and, since 2015, an additional 700,000 Nepalis have been pushed into poverty. Overcrowding, malnutrition, and little to no income—factors associated with poverty in Nepal—heighten individuals’ susceptibility to COVID-19 and render adherence to public health safety measures, as well as access to medical care, nearly impossible. To prevent the worsening of these risk factors, a transparent and efficient COVID-19 response plan is necessary; six months in, this has yet to materialize.

The Nepalese government has pervasively and glaringly mismanaged their pandemic response: it faces various allegations of instigating corruption, manipulating food prices, and neglecting quarantine facilities. Given Nepal’s Least Developed Country (LDC) status, the economy cannot bear the cost of further corruption. Poor governance diverts necessary funds from COVID-19 relief efforts and heavily undermines future plans for economic recovery that could secure the lives of the quarter of the population that lives below the United Nations poverty line or the families that depend on remittances, which make up 26 percent of the economy. A devastated economy will not only impede growth but will also aggravate long-standing patterns of structural inequality. Thus, corruption and the mishandling of funds by the Nepalese government have exacerbated the economic impact of the pandemic. In May, Nepali families that lost income due to COVID-19 represented one-third of families across the country—but in earthquake-affected areas, they represented 87 percent of families. It is thus imperative the government cut corruption to protect vulnerable groups and mitigate a widening inequality gap.

Heightened divisions between the newly unified Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist) and Maoist Centre have led to a mismanaged pandemic response. Three years post-unification, different competing factions within the ruling party are still alive; according to co-chairs KP Sharma Oli—the current prime minister—and Pushpa Kamal Dahal, “betrayal and counter-betrayal continue to prevail.” Internal fissures hamper future economic recovery and threaten to quash years of positive growth. Ganesh Sah, a Standing Committee member, attested that “though the COVID-19 issue was listed as the second agenda when the Standing Committee meeting started on June 24, it was rarely discussed in the 80 days, except on some rare occasions.” Instead, party members noted leadership spent the time deadlocked in a power tussle: since a faction in the party led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal channeled its energy to weakening Prime Minister Oli, governing leaders did not place enough emphasis on the pandemic and its impacts. Continued intra-party disputes and dismissal of the pandemic will lead to greater suffering and delay urgently needed measures to weather the aftershocks.

A further hindrance to COVID-19 relief efforts routinely lies in Oli’s ineffective governance practices. The prime minister conducts misinformation, denial, and nationalist campaigns to silence his waning popularity and credibility. To date, there is ample evidence that incompetent leadership is costing innocent lives; given Oli continuously undermines the severity of COVID-19, Nepal may be heading down a similar path. In conjunction, the Oli administration prioritizes political maneuvers that aim to consolidate the prime minister’s power—censorship of the media, controversial new ordinances, and a border skirmish with India, to name a few—over COVID-19 relief efforts that benefit the general population. Such decision-making undermines democracy in favor of creeping authoritarianism and deepens divisions within the ruling party. Oli’s inability to thrive without nationalist rhetoric will catalyze eventual calls for his resignation. A change in leadership amid a crisis is not ideal for a country historically plagued by political instability, but fresh leadership and energy are necessary to mitigate the impending repercussions and re-establish effective governance that can adapt to new challenges such as COVID-19.

The government is working slowly toward improving its pandemic response, starting with supporting the informal sector. In May, the government announced plans to provide informal workers additional opportunities to participate in public-works projects for a subsistence wage. Job creation is indeed a significant start, but this should be done in conjunction with an increase in social spending to temporarily extend coverage to informal workers. Without a basic level of income security and access to healthcare, Nepali individuals are likely to remain trapped in vicious cycles of vulnerability, poverty, and social exclusion, which pose challenges to their welfare, human rights, and the country’s overall economic and social development.

Going forward, Nepal must clean up its governance and ensure a robust post-COVID-19 reconstruction plan to fully embrace democracy, foster economic growth, and promote individuals’ wellbeing. Minimizing corrupt practices will not be instantaneous but enforcing accountability mechanisms and electing new leadership are a start. Given that corruption permeates much of Nepal’s political sphere, civic engagement and pressures from international institutions (such as the UN) is imperative to ensuring better governance and increased development effectiveness. By obtaining and disseminating information, exposing abuses of power, and mobilizing public support, civil society organizations can apply heavy political pressures to improve governance.

The pandemic carries heavy consequences for Nepal’s future; the outbreak will hit nearly every sector of the country’s economy, shaving up to 0.13 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) and rendering up to 15,880 more jobless. To minimize the incoming impacts, the government, international institutions, and civil society organizations must work together to eliminate corrupt practices and revitalize relief efforts to protect a greater share of the population.

Capucine Querenet is an intern at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading:

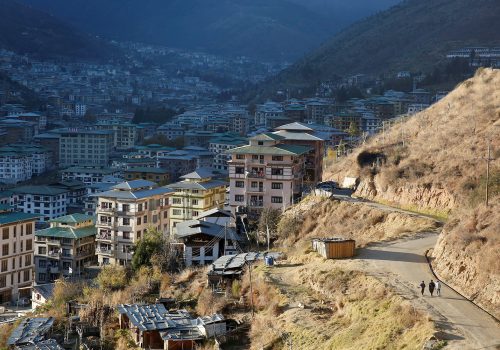

Image: Nepalese youths holding placards maintain social distance as they take part in a protest demanding better and effective response from the government to fight the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak as the number of infections spikes, in Kathmandu, Nepal June 13, 2020. REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar