On July 25, the European Union and the United States took an important step in de-escalating the threat of a trade war by agreeing to not only begin walking back US tariffs on European steel and aluminum and Europe’s retaliatory measures, but also by starting to discuss an ambitious forward-looking agenda for reducing trade barriers and expanding trade liberalization in other sectors, such as energy, soybeans, services, and non-tariff barriers (NTBs).

On July 25, the European Union and the United States took an important step in de-escalating the threat of a trade war by agreeing to not only begin walking back US tariffs on European steel and aluminum and Europe’s retaliatory measures, but also by starting to discuss an ambitious forward-looking agenda for reducing trade barriers and expanding trade liberalization in other sectors, such as energy, soybeans, services, and non-tariff barriers (NTBs).

The goal of eliminating NTBs is laudable. We welcome the transatlantic effort to find a way out of the dead-end associated with increased trade barriers. As we noted before the White House meeting between Presidents Juncker and Trump, such an approach could provide an off-ramp from the current trade war dynamics, while delivering considerable opportunities for economic growth and high-value job creation.

But achieving this goal even on a bilateral basis between the world’s two largest economies will be far from easy. It will require regulatory changes to currently protected sectors in the United States as well as the European Union. Twice in the last decade, regulatory policy differences have repeatedly stymied transatlantic trade liberalization efforts in both the Transatlantic Economic Council (TEC) and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations. If the United States and EU can get some easy initial wins, leverage the opportunity of new technologies, and respect existing regulatory processes, however, they can avoid the pitfalls that posed problems for prior transatlantic negotiation efforts.

What are NTBs?

Increased economic integration during the post-war era led trade policy officials to seek reductions in trade frictions from local regulations and bureaucratic processes that stop goods (and services) at the border, known as NTBs. Policy makers have been chipping away at NTBs for years.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) defines these as:

- Import licensing restrictions (administrative or applications processes beyond those required for customs administration);

- Rules for the valuation of goods at customs;

- Requirements for pre-shipment inspections;

- Rules of origin (designed to eliminate efforts to bypass free trade agreements by relying on trade partners to serve as trans-shipment points for goods made in third countries); and

- Restrictions on inward investment (usually on the grounds of national security concerns).

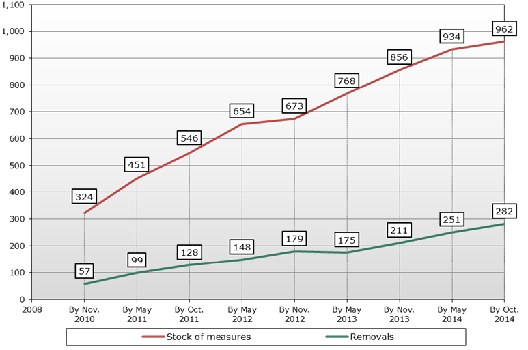

The Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (the TBT Agreement, currently under review at the WTO) seeks to ensure that domestic regulations apply on a non-discriminatory basis to domestic and foreign goods. Following the financial crisis in 2008, tariff barriers generally increased globally amid increased domestic protectionism and a general backlash against global trading relationships, as shown in the below graph from the WTO. This policy environment increased the incentive for policy makers to find alternative mechanisms that enhance efficiencies in existing trade relationships by reducing unnecessary regulatory frictions associated with NTBs.

For example, the Group of Twenty (G20) countries recently led an effort to create a multilateral Trade Facilitation Agreement, which went into force in February 2017. The goal was to accelerate administrative customs processes, increase transparency regarding fees, increase the use of advanced technology in the customs process, and decrease the amount of corruption associated with customs processes globally. The World Economic Forum indicates that implementation of this agreement would increase cross-border sales by small- and medium-sized companies globally.

This snapshot of global NTB policy trends illustrates the scale of the challenge that awaits transatlantic policy makers seeking to make progress on the current initiative. An emphasis on NTBs will focus on regulatory standards, established through national processes, that importantly reflect local values and norms (e.g., food safety standards, auto safety standards, pharmaceutical safety standards, environmental protection, and financial regulatory policy). Even when regulatory standards are applied in a non-discriminatory manner consistent with the TBT Agreement, however, they can generate barriers to cross-border trade by increasing compliance costs or requiring domestically-produced versions of the same product. Transatlantic negotiators face a substantial challenge, but they also have much to gain by exhibiting leadership in this area.

Why should the United States and the EU care about NTBs?

The United States and the European Union represent the world’s largest bilateral economic relationship. Recent data from the European Union indicates that the United States is the largest export market for EU goods (accounting for 20% of EU exports) while the EU is the second largest market for goods made in the United States (accounting for 13.6% of EU imports). Both imports and exports have grown dramatically since the recent financial crisis. Recent data from the United States Trade Representative indicates that trade in services exports from the United States ($231bn) were nearly equivalent to goods exports ($270bn).

In addition, the United States and the EU have the largest mutual investment relationship in the world, which helps support a significant part of transatlantic trade. US and European firms employ more than 9 million on both sides of the Atlantic with up to 5 million more jobs supported by the resulting economic activity.

Given the depth and interconnectedness of the transatlantic economic relationship, even small efficiency gains associated with decreasing or eliminating NTBs at the transatlantic level could therefore generate substantial economic benefits on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet policy makers have failed consistently in the last decade to decrease NTBs despite the existence of robust, science-based regulatory processes, and considerable high level political will.

How can the EU and the United States make progress on NTBs?

The new pledge to reduce or eliminate NTBs represents the third significant transatlantic initiative in this area since 2007. Policy makers are now proceeding down a familiar road with well-known and often emotional pressure points both in the goods sector (chlorinated chicken and genetically modified seeds) and in the services sector (financial services and professional services). If they are to succeed where the two preceding transatlantic efforts have failed, they should keep in mind some lessons learned:

Start Small: Policy makers should focus on a limited set of regulatory policy measures where a high degree of policy convergence already exists and use these areas to build confidence and establish solid working relationships before tackling more complex or emotional issues. It is possible that the soybeans export portion of last week’s agreement represents such an initiative. The European Commission recently reported that as of July 2018 (before the Trump-Juncker meeting), the United States represented 37% of all EU soybean imports, with a substantial increase (+283%) from July 2017. In July 2017, the United States represented only 9% of all EU soybean imports. The substantial increase likely reflects the European Commission’s July 2017 decision to allow certain genetically modified soybean varieties.

Take on Newer Technology: Cross-border regulatory cooperation and NTB reductions have foundered in part because policy makers to date have focused on traditional areas where domestic political priorities often have decades of entrenched perspectives. Change is hard everywhere and always. The deepening technological revolution underway in Europe and the United States presents opportunities for policy makers to identify areas where rules do not yet exist or are still evolving and where NTBs could more easily be reduced. Safety standards regarding autonomous vehicles and vehicles using alternative energy, for example, have not yet been fully defined on either side of the Atlantic, meaning that if European and American officials define new standards together, they can eliminate the application of NTBs to new vehicles.

Respect Existing Regulatory Processes: The current political environment on both sides of the Atlantic remains hostile to cross-border trade generally. NTB reductions will acquire more political support if they can be implemented by working with the grain of existing domestic regulatory processes. It will be important for policy makers to avoid giving the impression that trade agreements represent attempts to evade or avoid existing national regulatory processes.

Serious economic studies have argued that there is significant economic gain for both Europe and the United States in reducing non-tariff barriers. If they begin with carefully-selected sectors to get some early wins, the United States and the EU can start generating momentum to harvest these potential gains.

The EU has never given up imposing its own norms and standards on its partners and will continue to do so even if it fails to continue a dialogue with Washington. If the United States and the European Union can agree and start a process, however, they will have a much more profound impact on others and make sure that other actors – like China – do not try to take over the steering wheel.

Barbara C. Matthews is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program. Follow her on Twitter @BCMstrategy.

Earl Anthony Wayne is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program. Follow him on Twitter @EAnthonyWayne.

Image: A worker adjusts European Union and U.S. flags at the start of the 2nd round of EU-US trade negotiations for Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership at the EU Commission headquarters in Brussels November 11, 2013. (REUTERS/Francois Lenoir)