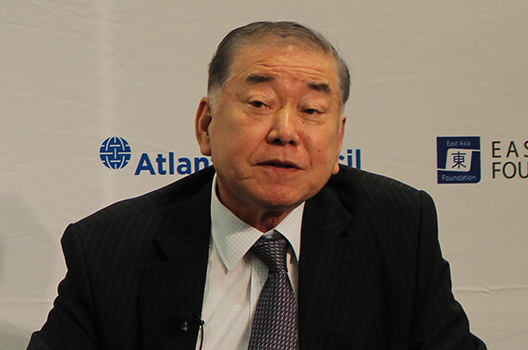

Following the failure of the February summit in Vietnam between US President Donald J. Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, “there is a huge trust gap between Washington and Pyongyang,” Chung-in Moon, special adviser to South Korean President Moon Jae-in for unification, foreign, and national security affairs, said at the Atlantic Council in Washington on June 19. “In order to break that trust gap,” Moon added, “North Korea should take some proactive actions.”

Little progress has been made between the United States and North Korea since Trump and Kim met in Hanoi, Vietnam, on February 27 and 28. Speaking at an earlier session of the 2019 Atlantic Council-East Asia Foundation Strategic Dialogue, US Special Representative for North Korea Stephen Biegun said US-North Korea diplomacy was in a “holding pattern” over continued differences between the two sides on the exact definition of complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization (CVID).

Moon described the disagreement between Pyongyang and Washington as the difference between a US-favored “big deal,” which would see North Korea dismantle all of its nuclear weapons and missiles in return for comprehensive sanctions relief, and Pyongyang’s preference for a “small deal,” which would require North Korea to dismantle its nuclear enrichment facility in Yongbyon in return for sanctions relief.

Moon argued that this definition of the negotiations as “denuclearization on the one hand and sanctions relief on the other” will not break the stalemate as Washington is clearly not prepared to lift sanctions until denuclearization is achieved, while Pyongyang sees sanctions relief as a precursor to any denuclearization.

Indeed, Moon said many in Pyongyang are irritated that sanctions relief has not yet occurred as a result of the first Trump-Kim summit in Singapore in June 2018, when both leaders committed to “new relations.” The “North Korean understanding is that [a] new relationship starts with the relaxation of sanctions,” Moon explained, as “North Korea sees sanctions as a very important indicator of hostile intention and policy [from] the United States.”

Moon argued that the key to breaking the impasse between the two countries could be the use of “political assurances, meaning normalization [of US-North Korean diplomatic ties], and military ties… the most important part [being] a nonaggression treaty.” Offering these promises, which go to the heart of North Korea’s desire to have nuclear weapons to protect itself, would give Pyongyang the cover it needs to complete denuclearization, which then would trigger the rollback of sanctions, he said. “If the United States can come up with some sort of institutionalized guarantee… then there is a very good chance that Kim Jong-un gives up his nuclear weapons. Then sanction issue will be automatically resolved,” he added.

The joint statement issued after the Singapore summit, said Trump had “committed to provide security guarantees” to North Korea while Kim “reaffirmed his firm and unwavering commitment to complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” So pushing these to the front of the process should not be too big of a step, Moon said.

The first step in this process, Moon said, is tangible action from North Korea to show the United States that it is serious. “North Korea [should take] action. Otherwise nobody in Washington will believe that the North Korean leader has any intention or will to denuclearize,” he said.

Kim has plenty of options to do this, Moon said, including the North Korean leader’s offer to close the Yongbyon nuclear enrichment facility. Moon also pointed out Kim’s promise to dismantle the Tongchang-ri missile site and the apparent destruction of the nuclear test site at Punggye-ri. Kim could regain considerable trust in Washington, Moon suggested, if he followed through on his Tongchang-ri promise and allowed international observers to examine the Punggye-ri site.

“North Korea’s leader has been talking about actions and committed himself, but we haven’t seen any concrete actions,” Moon lamented.

Should Kim actually take some of these tangible steps, Moon said, “North Korea deserves some reward from our side,” which could include security guarantees. While Kim has done nothing to gain the trust of the United States, Washington “has not been very clear about what it can give to North Korea in return” either, Moon added.

When asked by former US undersecretary of state and Atlantic Council board director Paula Dobriansky whether Kim was actually serious about denuclearization, Moon said that when he joined a South Korean delegation for a meeting with their North Korean counterparts last September “we could sense that North Korea is really committed” to the idea of denuclearization. Moon reported that during the April 2018 meeting between Kim and the South Korean president, the North Korean leader said “denuclearization is the will of my father and grandfather,” a reference to former leaders Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-Il.

But, Moon warned, “time is on nobody’s side.” He worries that “starting from 2020, North Korea may be taking much worse actions” than their nuclear weapons test in 2017. Kim must show that he is ready to work with the United States, Moon maintained, but Washington must also be ready to play ball.

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Image: Chung-in Moon, special adviser to South Korean President Moon Jae-in for unification, foreign, and national security affairs, speaks at the Atlantic Council on June 19, 2019.