Let us be blunt. The U.S. Department of Defense and the entire federal government face a fiscal crisis far worse than any threat posed by al-Qaida, Iran or North Korea.

Barring another Sept. 11th shock to the system, the massive debt and deficits will force defense budgets to shrink dramatically. Sadly, the U.S. government may be presently incapable of taking appropriate action to deal with these desperate economic realities.

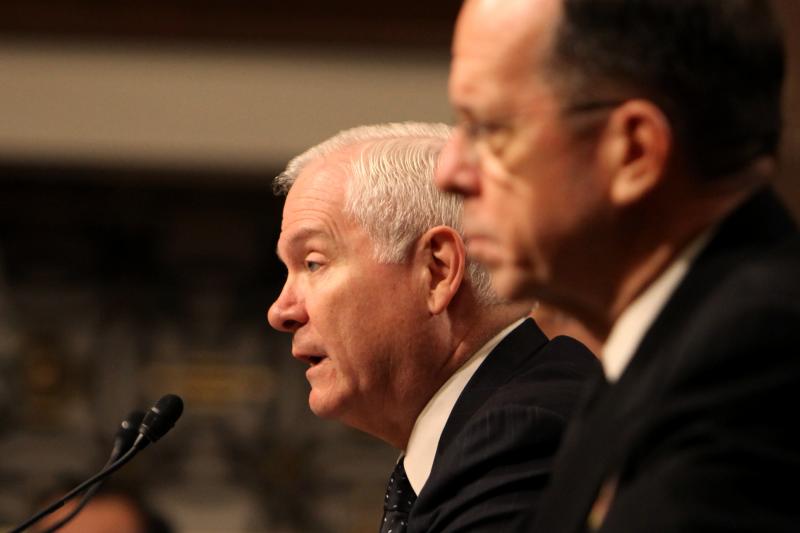

About fiscal tsunamis and the Pentagon, former Defense Secretary and Vice President Dick Cheney observed that every time we built defense down “we screwed it up.” Unfortunately, in the nearly two decades since that statement was made, the political process has become even more pernicious and partisan. Fortunately, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Adm. Mike Mullen see what lies ahead.

Last month, Gates began battening down the fiscal hatches. He cited the need to generate at least $100 billion in savings over the next five years as part of a grand bargain with the U.S. Congress in anticipation of these looming cuts. If Congress would guarantee 1 percent annual real growth for defense, the Pentagon would find the additional 3 percent-4 percent needed to fund the wars through savings inside the department. The first of these will come from symbolic but modest reductions of senior military and civilian personnel; the closing of Joint Forces Command and two other defense agencies and obviously major efforts to cut waste and duplication.

Those are important steps. But they are only first steps. Far more, both in number and especially in impact, are crucial. The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan exacerbate this predicament. No one wishes to abandon our troops in combat. Yet, both conflicts show few signs of success and may be deteriorating.

Overall defense spending including the Pentagon budget; supplemental funding of the wars; nuclear weapons programs funded in the Energy Department; healthcare; and veterans costs, is close to $1 trillion a year. The cost drivers are people, operations and, of course, buying the sinews of war and support for them. In broad terms, the annual price tag on one U.S. serviceman or woman is around $300,000.

That is why so many positions from food providers to guards have been contracted out. An extra 92,000 ground forces were added several years ago to deal with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Now those extra numbers are about to become unaffordable.

Overlay a regulatory, oversight and legislative galaxy of bureaucracy and political processes that probably add an additional 10 percent-20 percent costs for overhead and the continued pursuit of ever better technology to ensure our forces have the most modern weapons systems, the result is a perpetual motion machine dependent on greater annual spending just to keep even. And given congressional responsibilities to constituents whose jobs, local bases and programs depend on defense spending, making large cuts is always difficult and inefficient.

Gates and Mullen understand this. The issue is whether that understanding will make a difference given the obstructive power of the vast defense-military-industrial-congressional complex. However, if we are to keep a modern, well-trained professional military, tough, unpalatable and even Draconian measures are needed.

“Out-of-the-box,” and even radical, thinking to unearth fresh ideas is essential and probably unlikely. The fact is that budget and economic realities mean that we may have to reduce the size of the Defense Department by one-quarter to one-third or more over the coming years, something that is already happening in the United Kingdom. The political opposition to such steps will be thermonuclear.

What is needed is a strategy based on a new foundation. The first pillar is maintaining a highly professional yet smaller military. The second is finding a 21st-century equivalent of mobilization.

Within this smaller active duty force of perhaps 1 million, some part, say around one-quarter to one-third, would be in “cadre” or modified lower condition of readiness “stand down” status with the ability to return to full active service in 6 to 9 months.

To gain this capacity, exploiting the “knowledge revolution” with distance learning and other techniques is essential to educating and training the total force. We will no doubt buy fewer numbers of very capable and expensive systems (and drive up unit costs dramatically with the attendant political debate). Hence, applying funds selectively for keeping not a “warm” but a “tepid” industrial base may become a necessity.

The Pentagon arguably faces its most serious post World War II fiscal crisis at a time when our enemies are in some ways more dangerous, clever and less affected by our arms, no matter how brilliantly used. In this environment we must think rather than spend our way clear of danger. Otherwise, the dreaded post-Vietnam “hollow force” could seem favorable in comparison.

Harlan Ullman is Senior Advisor at the Atlantic Council, Chairman of the Killowen Group that advises leaders of government and business, and a frequent advisor to NATO. This article was syndicated by UPI. Photo credit: UPI.

Image: Gates-and-Mullen-testify-in-Washington.jpg