US President Donald J. Trump’s September 4 decision to rescind a program that has allowed hundreds of thousands of young people who were illegally brought to the United States to remain in the country undermines his administration’s stance towards Central America.

US President Donald J. Trump’s September 4 decision to rescind a program that has allowed hundreds of thousands of young people who were illegally brought to the United States to remain in the country undermines his administration’s stance towards Central America.

While Trump reportedly vacillated until the last hour about whether to end the program that provided protection to these young people—the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program—immigration hawks ultimately prevailed.

There is uncertainty about the immediate impact on DACA-eligible children—known as Dreamers—of the decision to unravel the program former US President Barack Obama put in place by executive order in 2012. Trump has effectively deferred to the US Congress to revamp the nation’s immigration laws and protection for DACA recipients over the next six months.

Beyond the domestic impact of ending DACA—a program that was viewed favorably by both Republican and Democratic members of Congress—the foreign policy implications of Trump’s decision are significant.

Ending DACA exposes a fundamental flaw in the administration’s strategy towards Central America—the failure to recognize that domestic immigration policies and foreign policy strategies go hand in hand. According the Migration Policy Institute, there are more than 200,000 DACA-eligible migrants from the three countries of Central America’s Northern Triangle —El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

In June, US Vice President Mike Pence travelled to Miami for a summit with the presidents of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In his speech, Pence reaffirmed the US commitment to help the three countries bolster economic development, root out corruption, and combat organized crime as part of a broader strategy to improve prosperity and security in the region. “We’re in this together,” Pence emphasized.

Policy decisions made by the Trump administration, however, indicate otherwise. The White House’s foreign assistance budget proposal for the Northern Triangle cuts aid to El Salvador by 40 percent, and by a third for both Guatemala and Honduras. While the administration’s hardline stance on immigration has in fact served as a deterrent to those intending to come to the United States, reducing economic development and security assistance to the region would arguably increase migration from the three countries to the US. A strategy that prioritizes deportations over solving the root causes spurring migration will inevitably be insufficient.

In addition, the US Department of Homeland Security in August ended the Central America Minors (CAM) program, to which more than 13,000 minors fleeing violence had applied. The administration has not yet made a decision on whether to extend Temporary Protection Status (TPS)—a program protecting Central American migrants since the turn of the century—to the 195,000 and 41,000 citizens of El Salvador and Honduras, respectively, who are currently covered by the program. This increases uncertainty among Northern Triangle migrants currently living in the United States.

Ending DACA further complicates an already difficult institutional situation for the Northern Triangle. Given the three countries’ limited reintegration capacity, a combination of the above mentioned factors,—exacerbated by the large amount of potential DACA-eligible returning migrants—would overwhelm local authorities, undermining their ability to provide proper social and economic assistance to returned migrants. Such disenfranchisement of returned migrants has, in the past, provided fertile ground for gangs such as MS-13 and Barrio 18 to recruit prospective members.

However, the return of DACA-eligible migrants has an additional layer of complexity that is unique to the program. Most of the youths eligible for the program and vulnerable to deportation if the program is effectively rescinded identify as American as they have lived in the United States for most of their lives. English is their preferred language; their Spanish tends to be limited or nonexistent. Reports indicate that they do not feel at home in their countries of birth.

Should they be deported, the same reports demonstrate that those who grew up in the United States, protected by DACA, are willing to risk embarking on a dangerous future trip back to the United States in order to reunite with their friends and family. While the administration’s immigration stance may have served as a deterrent to Central Americans considering migrating north, it does not seem that that will be the case for Dreamers who consider the United States their home.

If the Trump administration pledges to support economic development and improved security in Central America, but simultaneously pushes draconian immigration policies that overburden local institutions, it is simply shooting itself in the foot. The ball may now be in Congress’ court, but Trump should understand that his decision to rescind DACA will ultimately undermine his administration’s foreign policy and his goal of securing US borders.

Juan Felipe Celia is a program assistant in the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. You can follow him on Twitter @jfcelia.

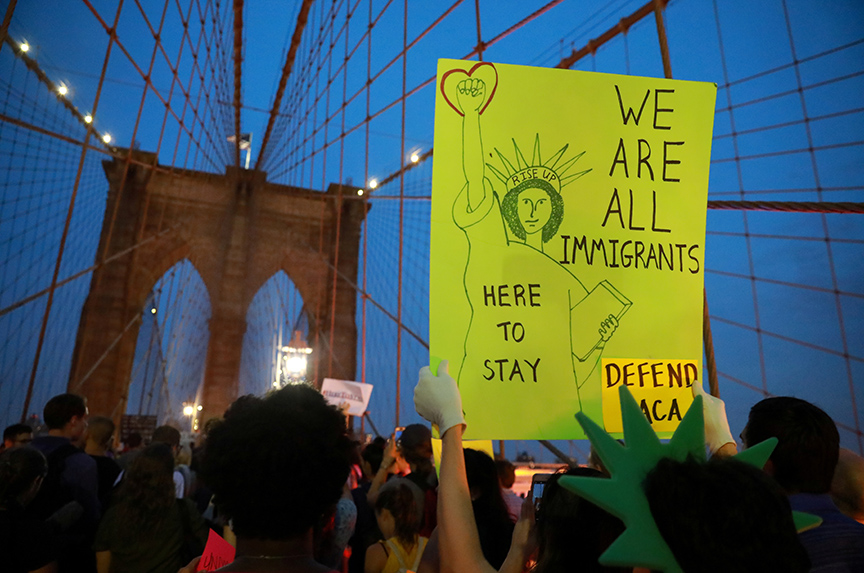

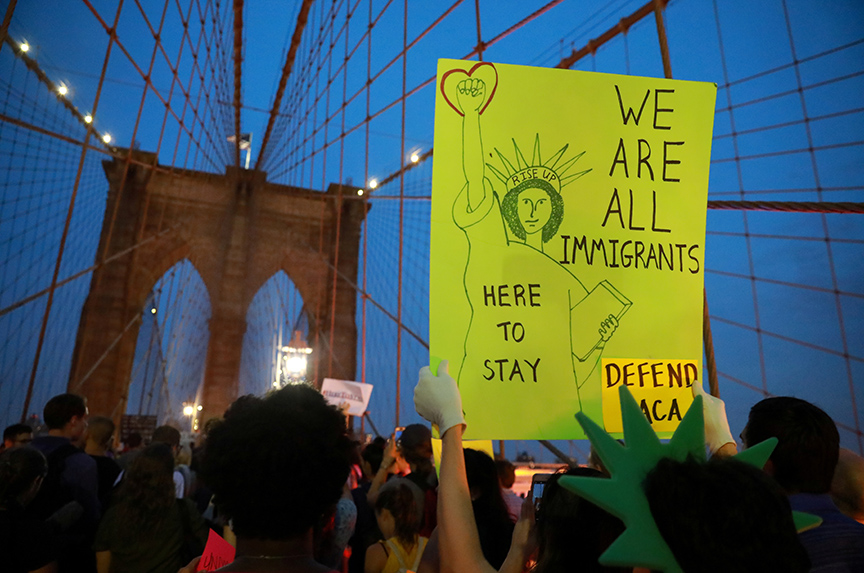

Image: People marched across the Brooklyn Bridge in New York on September 5 to protest US President Donald J. Trump’s decision to wind down the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. The program has allowed hundreds of thousands of young people who were illegally brought to the United States to remain in the country. (Reuters/Stephen Yang)