In recent years, Russia has become growingly visible in the Balkans. Its forays into the region fuel the perception of the region as a geopolitical battleground, with Turkey, China, and even the Gulf monarchies also posing a challenge to the West. Russia stands out from the list. Unlike other external players, Moscow has wholeheartedly embraced the role of spoiler acting against Western interests. Moscow is vehemently opposed to ex-Yugoslav countries joining NATO and is no friend of the European Union (EU) either, even though its attitude to its enlargement remains ambiguous. Russia is also unique in terms of the range of capabilities it brings to bear. Its toolbox spans hard military power, economic instruments— particularly with regard to the energy sector—elements of what analysts define as “sharp power” (e.g. disinformation and disruption), as well as a degree of cultural appeal or “soft power” rooted in shared religion and history with a number of South Slav nations. Though it lags considerably behind the EU and NATO, Russia has proven an increasingly influential actor in the region.

Russia’s strategy

The Western Balkans are part and parcel of Russia’s strategy to establish itself as a first-rate player in European security affairs, along with other major states such as Germany, France, and the UK. Since the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, the region has been at the forefront of debates on critical issues such as transatlantic relations, the EU’s security and defense policy, and NATO/EU enlargement. Having a foothold in the Balkans means having a say on those strategic matters, which are of direct consequence to Russia. Moscow is driven by geopolitics, with other concerns such as economic interests or historic bonds with the South Slavs or the other Orthodox nations playing a secondary role. It sees the Balkans as a vulnerable periphery of Europe where Russia can build a foothold, recruit supporters, and ultimately maximize its leverage vis-à-vis the West.

There is no doubt that Southeast Europe lies well beyond what Russia considers its privileged sphere of geopolitical interest. In economic, social, and also purely geographical terms, the former Yugoslav republics and Albania gravitate towards the West. Russia’s only option is to act in an obstructionist manner to undermine the EU and NATO, making use of the Balkans’ own vulnerabilities, whether through nationalism-fuelled disputes inherited from the 1990s, pervasive corruption and state capture, or citizens’ distrust in public institutions. Rather than drawing the Western Balkans into its own orbit, a costly exercise for a nation whose gross domestic product (GDP) is comparable to that of Spain, Russia is looking for leverage in the region it could then apply to the EU and the United States. Influence in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, or elsewhere is a bargaining chip in Russia’s strategic competition with Western powers. From Moscow’s perspective, projecting power in the Balkans is tantamount to giving the West a taste of its own medicine. If the Europeans and the Americans are meddling in its backyard—Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, or any other part of its ‘near abroad’—Russia is entitled to do the same in theirs.

The perception that the United States humiliated Moscow during the Kosovo crisis of 1999 is also at play, justifying engagement with the region as a means to right past wrongs. Russia’s so-called return to the Balkans, in no small measure occurring through invitation from local officials, is payback to the West for its own arrogance. Lastly, active involvement in the region underscores Russia’s role in European security, particularly on salient and politicized issues such as NATO’s expansion, the talks between Serbia and Kosovo, or the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This awards Moscow the coveted status of a top-tier power, whose interests and networks spread far and wide across the Old Continent and beyond. Russia can leverage scarce resources to attain maximum payoff, be they diplomatic or commercial gains, or simply confirmation of Moscow’s status as an indispensable international actor. Not being bound by any particular ideology or normative aspirations, as was the case with its Soviet predecessor, gives present-day Russia an advantage too.

Moscow’s toolbox

To attain its objectives, Russia uses coercion, co-optation, and subversion.

As a rule, coercion through military means is of lesser significance for the Western Balkans than for other regions exposed to Russia. At the same time, soft coercion verges on disruption and Russia uses many different instruments to assert its interest: hard military power, manipulation of economic ties, interference in other countries’ internal affairs, and targeted information campaigns to influence public opinion. Interference in domestic politics is far from rare. A case in point would be the support Russia has given to nationalist activists in pro-EU and NATO countries such as Montenegro and North Macedonia. Peaceful political action (anti-government demonstration) could spill over in violence. Other examples of soft coercion, practiced in the post-Soviet space and in the Balkans, include trade embargoes and cyberattacks.

Co-optation is Russia’s instrument of choice in the Western Balkans. Moscow has built partnerships and alliances with local power holders in Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Republika Srpska. Motivations for choosing to work with the Russian state, or its proxies and subcontractors, differ; some benefit from direct monetary gain in the form of rent, others gain advantage in terms of managing the inter-state balance of power at the regional or domestic levels. Thus, Serbia has aligned with Russia to maximize its leverage over the Kosovo issue but also because successive governments sought to draw benefits from investment and business ties, no doubt including kickbacks and side payments. Russia has also proven an indispensable ally for Milorad Dodik in the effort to consolidate his grip over Republika Srpska and resist pressure from the West, from the major Bosniak parties favouring greater centralization of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and from the opposition in the Serb-majority entity.

Subversion is exemplified by tactics such as (dis)information campaigns and open or covert support for radical anti-Western actors (parties and civic associations). In the Western Balkans, the best example is furnished by efforts to block the accession to NATO by Montenegro (in 2015–16) and North Macedonia (in 2017–18). In both cases, Moscow fanned the flames of internal crises to thwart NATO’s expansion. One benefit of subversion is its low cost. Russia does not have a long-term plan for the Balkans, aside from obstructing the West, and is not prepared to expend scarce economic and military resources and run risks, such as a direct confrontation with NATO. What it does instead is exploit weaknesses and blind spots in Western policy to claim a co-equal status and possibly generate leverage that could be used as a strategic bargaining chip with the United States and Europe. Another merit of subversion, as well as of co-optation, is that it is amenable to outsourcing. Indeed, Russian influence works through both formal and informal channels. State institutions such as Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs are the tip of the iceberg. Multiple other players, both within the state and outside it, are also involved.

Policy recommendations:

Do not give up on NATO and EU enlargement. The countries of the region should be brought into Western institutions sooner rather than later. Any delays caused by the lack of willingness or commitment to expand on the part of the current member states reinforces the Balkan people’s sense of abandonment. This fuels anti-Western attitudes and empowers the Kremlin and its proxies. NATO in particular should deepen strategic cooperation with Serbia and encourage the new government in Bosnia and Herzegovina to activate the country’s membership action plan (MAP). The EU should launch accession talks with Northern Macedonia and Albania.

Focus on democracy and the rule of law. Integration into the EU and NATO is not a goal in itself but a means to an end. Democratic consolidation and gains in the rule of law are critical to countering malign influence from the outside. Western policy should therefore focus on the underlying flaws that enable Russian interference. The West should encourage greater transparency in party financing, judicial reform, and good governance in the energy sector. This is the best path to building resilience in national political systems and responding to co-optation and subversion.

Foster pluralism in media. Russian influence is at its most potent in the information space. To respond, Western states and institutions should increase their support to alternative media that are not beholden to governments and/or oligarchic interests in the region. The pro-Kremlin viewpoint should be balanced by independent journalism. The goal should not be to fight propaganda with counterpropaganda. In fact, free media only gain credibility by freely offering a critical perspective on the EU, NATO, or Western policy more broadly. But they also hold Russia accountable for its foreign policy actions and provide a balanced and fair perspective on Russian politics and society. Most importantly, by scrutinizing power holders and business elites, the free media limit the ability of foreign malign actors to penetrate national politics by striking deals with local players.

Dimitar Bechev is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. Follow him on Twitter @DimitarBechev.

This piece is an adapted version of a policy report prepared for NATO Strategic Communications Center of Excellence in Riga.

Further reading

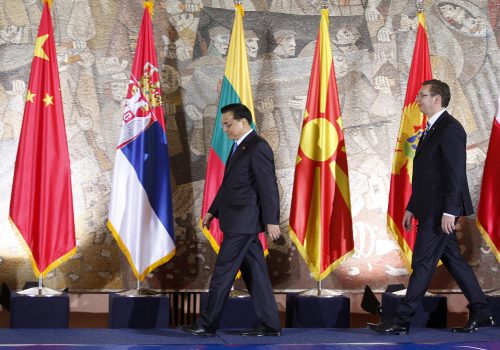

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with his Serbian counterpart Aleksandar Vucic in Sochi, Russia December 4, 2019. Sputnik/Mikhail Klimentyev/Kremlin via REUTERS