Earlier this month, the U.S. House approved a bill to establish permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) with Russia, also a newly-minted member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). These moves toward integrating the country into the global economy came at the same time as state oil company Rosneft took over the Russian-British partnership known as TNK-BP. But which is likely to have more impact on Russia’s fate?

While accession to the WTO can spur trade and competitiveness, don’t hold your breath waiting for Russian reform. The $60 billion Rosneft acquisition is likely to shape Russia well beyond the energy industry: it dims the already faint prospects of Russia diversifying and modernizing its economy to become more than a petrostate.

The focus of most assessments has been on how the deal will result in Rosneft, a state-controlled operation run by Putin associate Igor Sechin, becoming the world’s second-largest oil company that produces nearly half of Russia’s 10+ million barrels of oil per day. With BP buying back 19.75 percent of Rosneft shares, it is also heralded as a new model for joint ventures. This will be critical to the future of Russia’s oil industry, as the scale of investment and technologies required to develop offshore Arctic oil will require involvement of the supermajors, the world’s largest oil companies. The theory is that Rosneft will benefit from BP management skills and technology.

Some Kremlin watchers also see the the rise of Sechin in Moscow’s politico-economic hierarchy, making the Rosneft boss perhaps second only to Putin. Whether true or not, the larger issue is what the newly beefed-up Rosneft means for the future of the Russian economy.

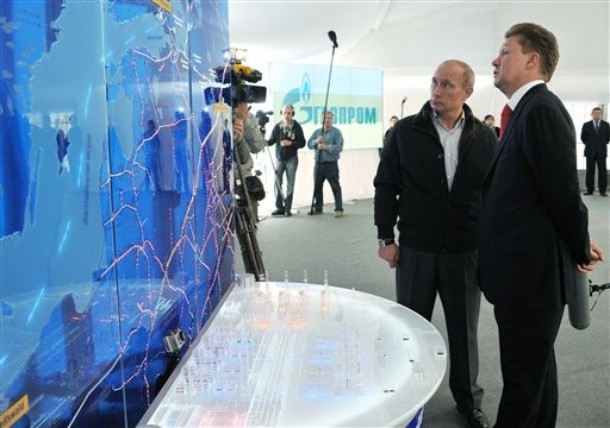

The Rosneft deal may have been—in effect, if not intent—Putin’s answer to the U.S. shale revolution. Until now, Gazprom, the state-controlled gas monopoly, has been the cash cow for Putin’s ruling political network. There is still some head-scratching as to the whereabouts of its $44 billion profits in 2011.

But since 2008, North American shale has taken off, driving down the price of natural gas. Gazprom’s future has grown increasingly problematic as the United States has emerged the world’s largest gas producer. Since 2008, Gazprom’s market value has plummeted from $365 billion to $120 billion. It is being sued by the EU for price gouging and already has had to drop the price of gas supplied to Europe substantially, as shale has driven down the price and made LNG on the spot market more attractive (now nearly 50 percent of the EU market). One need not be a conspiracy theorist to see that Putin’s rule will become more dependent on Russia’s energy sector—even as Gazprom fades from the scene.

More than 60 percent of Russian GDP is based on oil, gas, and other extractive industries. But Russia’s oil output is projected to reach a plateau from the middle of this decade onwards. The Rosneft deal offers new opportunities to harness western technologies to develop the very complex and difficult Arctic resources and the harder-to-get oil in Western Siberia needed to sustain current levels of oil production. It will also tend to reinforce Russia as a petrostate.

The Rosneft deal is likely to worsen what some call the “oil curse,” reinforcing state capitalism and reducing incentives for economic reform. Moscow’s ascension to the WTO membership in August—the last G-20 nation to do so—raised hopes that the imperatives of new trade obligations and benefits, of a Russia more integrated into the global economy, might spur some of the economic modernization that Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (remarkably low-profile these days) has talked up for some time—and that Putin himself included in his campaign rhetoric.

Russia ranks 120th on the World Bank’s ease of doing business index. Despite promises of reform, Moscow has yet to transform its image, if not reality, as a corrupt Mafia state. It is some distance from being competitive with major economies in most industrial and service sectors. Capital flight more than doubled in 2011 to $84.2 billion (from $33.6 billion in 2010) and is projected to be some $50 billion in 2012. The current political environment has made it more difficult for small and medium businesses to thrive.

Still more worrisome looking to the future is Russia’s brain drain. Over 1.25 million people have left Russia in the past decade, and in a recent poll in Novaya Gazeta, 62.5 percent of 7,237 readers surveyed said they were considering leaving because of discontent with the economic and political regime. This is playing out against the backdrop of negative demographic trends and projections suggest that Russia’s population will shrink from its current 142 million to some 124 million by 2030.

Russia’s president made a bevy of promises during the election campaign: large salary increases for teachers, civil servants and engineers; 25 million highly-skilled jobs; an increase in investment from 20 to 27 percent of GDP by 2018; a move up to 20th from 120th on the World Bank ease of doing business index; and a shift away from dependence on oil and gas. Running for president, Putin also pledged to fight corruption, decentralize power and reduce the state role in “non-strategic sectors” of the economy, echoing many of the reform goals touted by his predecessor Dmitry Medvedev in recent years.

But even if Rosneft provides Putin with walking-around money to reinforce his power structure, he is unlikely to have either the financial wherewithal or the political will to realize most of those things. The middle class that mushroomed on the oil boom of the past decade is increasingly restless. Moscow’s budget is pegged to oil at $115/barrel to avoid deficits, but many analysts project a soft oil market with very low U.S. and EU growth and slower growth in BRIC economies. The International Energy Agency (IEA) lowered its forecast for oil-demand growth in the last quarter of this year, and projects less than 1 percent growth (800,000 barrels a day) in demand for 2013. Oil prices may remain in the $70-$100 range. The Russian state bank is forecasting current account deficits as early as 2015.

Since resuming the presidency, Putin has shown few signs of any inclination toward serious reform or loosening control—with the possible exception of the energy sector. , Moscow’s behavior and failure to implement key reforms has deepened skepticism about its ability to change. Charges of rigged Duma elections, new laws that penalize protesters, require NGOs receiving foreign funds to register as foreign agents, and censor the internet—and not least, the emblematic Pussy Riot episode.

There is active debate within the Russian elite about the trajectory of Russia’s future. Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev put forward ideas for the past several years for diversifying the economy, building a competitive tech sector, bolstering rule of law, and taking advantage of WTO imperatives to boost industrial exports and the service sector. Putin has in his cabinet most of Medvedev’s liberal economic team such as Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich and Finance Minister Anton Siluanov. Moscow is gearing up for a new round of privatizations and according to the Economist has moved some 600 state industrial firms to a restructuring agency, Russian Technologies, which is attempting to create a Silicon Valley-type technology park outside Moscow.

But so far, these initiatives have had little effect. The problem is that moving in the direction of more economic modernization and less tight political control would likely put Putin’s power network at risk. Instead, as financial pressures from slow oil demand growth limit Moscow’s ability to deliver the goods to the Russian middle class, Putin appears to be keeping his focus on tight political control of the middle class and keeping oil at the center of Russia’s economy. As hinted at by the Rosneft deal, Putin seems inclined to try to modify the oil sector by allowing more joint ventures with Western firms, which have the technology to develop more difficult oil reserves in Western Siberia and the Arctic.

Such a scenario may keep Putin and his supporters in good stead in the short run. But it is difficult to see how Russia can become a globally competitive modern economy without a concerted effort to move toward a modern diversified knowledge economy, a more credible judiciary confronting corruption, and political reform. The interesting question is whether the middle class, whose benefits from this political path are minimal, will be seriously looking for alternatives when Putin thinks about a second term in 2018.

Robert A. Manning is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. He previously served in the State Department as a senior advisor to the Assistant Secretary for East Asia and the Pacific (1989-93) and on the Secretary’s policy planning staff (2004-08). This piece was first published in The National Interest.

Image: putingazprom.jpg