The Obama Administration’s recent announcement that it would begin a “targeted easing” of the decades-old sanctions regime currently in place against Burma has once again put into sharp focus questions surrounding the efficacy of sanctions as a tool of American foreign policy.

Although the wisdom of imposing sanctions on governments in Syria or Iran, for example, continues to be fiercely debated, the use of sanctions in Burma so far has proven to be the right tool and should remain a key feature of Washington’s policy towards the country as democratic reforms continue to unfold.

The imposition of sanctions on foreign governments is inevitably accompanied by criticism of their use. Skeptics commonly charge that sanctions are too easily circumvented, constitute only stop-gap measures, do more harm than good, and are thus ultimately ineffective in changing the behavior of authoritarian regimes. The arguments are familiar ones and are not entirely without merit in some cases.

In Burma, however, sanctions have resulted in a relative degree of progress, inducing the country’s new nominally civilian government to begin undertaking political reforms after years of repression and autocratic rule. Having suffered diplomatically, politically, and economically under the crippling web of sanctions imposed on them more than a decade ago, leaders in Burma now taking small steps to put their country on the path towards democratic reform and rejoin the community of nations in exchange for a lifting of the crushing sanctions.

Consistent with its policy of “principled and pragmatic engagement,” the Obama sdministration adopted a “carrot-and-stick” approach towards Burma. It indicated that it would consider lifting some of the sanctions if the government satisfied certain conditions and continued on a genuine path towards reform, but would keep sanctions in place if the administration was not persuaded by the rate or sincerity of progress.

Coordinating closely with key members of Congress, the administration enumerated several prerequisites the government had to satisfy before it would consider lifting sanctions. These conditions included holding genuinely free and fair parliamentary by-elections, unconditionally releasing the scores of political prisoners languishing in the country’s jails, ending its brutal assault on the country’s many ethnic minorities, and severing Burma’s murky and possibly illicit relationship with North Korea. In addition to these four steps, the Obama administration urged decision makers in Naypyidaw to enact legislation protecting freedoms of press and assembly, to adopt meaningful reforms to improve its troubling human rights record, and to revoke its draconian censorship laws.

Eager to see sanctions against the country lifted, the Burmese government took steps to satisfy each of these conditions, with varying degrees of success. The April parliamentary elections witnessed celebrated democracy activist and Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party win 43 out of the 44 seats it contested. Her election victory and the government’s tentative embrace of such democratic reforms prompted the Obama administration’s decision to begin easing certain sanctions against the country related to trade and investment. Sanctions, so far, seem to have proven both the right carrot and stick in Burma.

As leaders in Naypyidaw continue to implement reforms, however, the administration should still maintain some of the sanctions it has in place. It has rightfully resisted calls by the Burmese government, as well as others in the international community, for a comprehensive removal of sanctions beyond those measures already announced. The key reason for Washington to pursue such a course is because despite some positive steps, Burma’s path towards genuine democratic reform remains a long one. Although the reforms undertaken by the Burmese government so far have been substantive, they are still limited.

For example, while the NLD swept the April by-elections, the 43 seats it won represent fewer than 7 percent of the entire parliament, with the remainder of power still vested with the same generals and ex-military officials who have repressed the country’s citizens for half a century. A bitter standoff between Aung San Suu Kyi and the government over the wording of the oath of office she is required to take before taking her seat in parliament nearly shattered the fragile détente between the NLD and the nominally civilian government. Scores of political prisoners remain incarcerated in Burmese prisoners and Burmese government forces, while having signed ceasefires with some of the country’s ethnic minorities, have actually escalated conflict against others.

The situation in Burma remains precarious. The reforms initiated by the government are far from complete and are easily reversible. As a result, a wholesale lifting of sanctions would be premature. Instead, the Obama administration should maintain a measured approach towards the country in which it can carefully calibrate the use of sanctions to developments on the ground, easing, maintaining, or even tightening sanctions as necessary. Such an approach would strike the right balance between strengthening reformers and genuine progress in Burma on the one hand, while retaining meaningful leverage over efforts to promote reform on the other. The European Union has embarked on a similar course, suspending, rather than lifting, sanctions, for one year as it continues to monitor events in Burma.

Washington’s sanctions policy has served it well in Burma thus far. While the chorus of voices calling for the United States to lift more sanctions in place against Naypyidaw grows louder, the Obama Administration should remain steadfast in conditioning any additional reductions in sanctions on progress in Burma that is both genuine and permanent. Until then, a carefully calibrated approach with sanctions at its core remains Washington’s best option for promoting democratic reforms in a country whose citizens have been denied them for far too long.

Ronak D. Desai practices law in Washington, DC and holds a joint law and public policy degree from Harvard Law School and Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

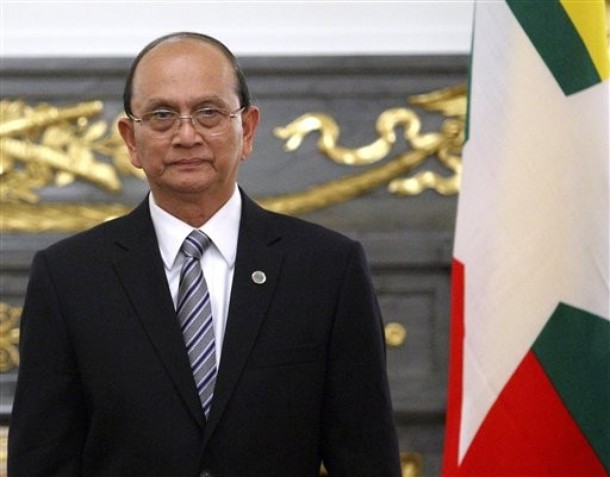

Image: theinsein.jpg