On November 24, a Croatian journalist revealed that Milorad Dodik, the president of the Bosnian Serb entity Republika Srpska, offered him money to cover up Dodik’s connection to the Hypo Alpe Adria Banka corruption scandal.

While many countries in southeast Europe pay lip service to democratization by reforming their institutions, politicians remain hostile to news outlets that aspire to be independent of political influence. When high-ranking officials believe that they can coerce or bribe journalists into hiding the truth, how can they foster such basic democratic principles as open political debate, transparency, and an informed electorate? Democratic institutional reform then becomes merely a façade.

In much of the world, even parts of Europe, when reporters file stories that implicate government officials in corruption scandals or simply focus on local social discontent, their governments cast them as enemies of the state. Two years ago, the Romanian Supreme Council for National Defense identified journalists as a threat to the country’s national security by influencing “the political decision-making process.” This past August Romanian President Crin Antonescu reaffirmed the Council’s position by ordering investigations of journalists who publish stories that attract negative international attention to Romania’s domestic policies.

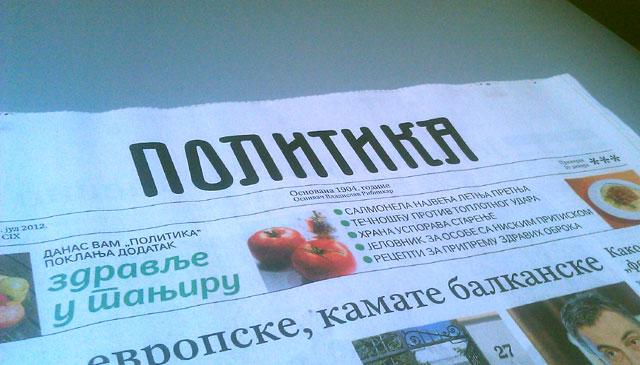

Serbian law does not require media outlets to divulge the names of major stakeholders, enabling politicians to develop cozy relationships with particular news outlets. Last July, East Media Group, a previously unknown company based in Moscow, bought fifty percent of Serbia’s oldest media outlet, Politika Newspaper and Magazines. The Association of Journalists of Serbia accused a major financier of Serbia’s Democratic Party of being East Media Group’s true owner. In addition, ministries often pay reporters to surreptitiously publicize ministry programs, degrading professional standards for journalists by pushing a political agenda from the start.

Simply put, journalists who want to cover sensitive topics that might challenge political elites cannot do their job. Aside from low wages and employment opportunity, investigative journalists risk physical attacks. Since early October, there have been at least five isolated attacks on journalists across Serbia, Kosovo, and Montenegro. One of the victims identified her attacker as a police officer. Physical attacks on journalists represent the most extreme violations of freedom of expression and information.

Despite the odds, independent media has successfully built parallel news outlets that establish their own professional standards for objective reporting, while covering topics that mainstream media overlooks. International news outlets often publish investigative pieces by journalists in southeast Europe, placing a spotlight on corruption, civil society, and local issues. Organizations such as the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network emphasize transitional justice in the region, by covering stories from all sides of the Yugoslav conflicts, including missing persons, victims, and rights of refugees; this is an approach that mainstream media in those countries have yet to incorporate into their reporting.

However, publishing stories internationally, rather than nationally, results in reduced readership comprised of the same minority that actively sought out information during communism and conflict. By limiting the development of independent media in southeastern Europe, governments are creating a self-imposed brain drain. Journalists who want to conduct investigative reporting either look to international media to publish their stories or emigrate for better employment opportunity. Without regional outlets where journalists can freely publish their stories, media rarely influences the internal political agenda.

Europeans speak out on press freedom in southeast Europe, but these statements have little impact on media reform. Following criticism from the European Digital Agenda Commissioner last month, the Bulgarian prime minister held a press conference to proclaim that “there is no censorship in Bulgaria” and proceeded to chastise one journalist who asked a question about the commissioner’s statement.

While the European Union includes media reform as a prerequisite for membership, oppressive media climates in Bulgaria and Romania—already EU members— show that media reform is low on the agenda. But it is not too late for Serbia, which is currently aspiring to join the European Union. The European Union should make media reform a priority for Serbia’s European Union membership. Western European countries should continue to fund professional workshops and other programs for journalists from southeast Europe to create a forum to speak out on these issues.

Media landscapes that operate under excessive political pressure, legislation that reduces government accountability, and threats against journalists stifle democratization in southeast Europe. From holding high-level officials accountable to fostering post-conflict transitional justice at the local level, independent media is essential for democracy.

Rena Linden is with the Council’s Patriciu Eurasia Center.

Image: politika.jpg