As NATO establishes a new Strategic Concept, the Alliance is re-focusing on its political and military purpose: to defend freedom in the face of those without ethics.

Freedom is under threat the world over, just as NATO begins the search for a new Strategic Concept (Stratcon 2010). This threat is posed by a dangerous new cocktail of terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, information technology and enormous flows of illicit capital in a global struggle between the state and the anti-state. Be it the challenge posed by the radically old or those, particularly in Europe, who endeavor to wish away the competition between new and old ideas that is implicit and endemic in strategic affairs.

In this struggle, the experience of Western armed forces in both Iraq and Afghanistan has emphasized a gap between military victory and political stability that has left many of NATO’s political leaders unsure as to the role of the Alliance and its armed forces in contemporary grand strategy. This has led to political defeatism in many NATO capitals at a time when financial constraint, stabilization fatigue and political correctness are combining to undermine the one truism that must be defended: namely, that the world is safest when the Western democracies are credible purveyors of strategic stability, founded on a credible, commonality of purpose backed up with both diplomatic and military tools self-evidently up to the job.

That is why the crafting of a new Strategic Concept will be critical. First, it must re-establish a contract between the political leadership and the security and military practitioners that support it, so that NATO can, once again, be restored as the cornerstone of the liberal-democratic security system for which the Cold War was fought. Second, credible military power remains and will remain the foundation of credible power just at the moment when Western armed forces are grappling with a new form of warfare. Hybrid warfare will see NATO’s armed forces having to fight to effect in the hazy realm between the conventional and unconventional, in which political courage and legitimacy will be almost as important as the strength of the force deployed. Stratcon 2010 must thus urgently re-establish the political and military purpose of the Alliance: the defense of freedom in the face of those without ethics. Such purpose will only be crafted if there is a sound understanding of three missions:

• to embrace and ease insecurity in and around the Euro-Atlantic community by offering both membership and partnership where applicable;

• to better protect the societies of the community against catastrophic penetration; and

• to project security worldwide through new power partnerships with cornerstone security states.

Therefore, if NATO’s armed forces are to be properly prepared for success in such a struggle, conceptual clarity at the outset will be essential, about the role of armed forces and thus the Alliance in preserving freedom in the face of a range of risks and threats. Unfortunately, old ideas about the preservation of state integrity assumed a threat from another state organized along similar lines. However, the dark side of globalization is one in which state borders are as much virtual as physical, and security and defense merge into the need to protect people – not just from threat, but the very fear of threat which weakens resolve and cohesion.

In such an environment, the utility of armed forces is not just in the fighting power they can bring to bear on open contact with threat, but as an organizing and planning nexus to both prevent threat becoming danger and coping with the consequences of such danger. No other organization in society possesses those attributes, and thus the military role of NATO will be to ensure that armed forces go about their business in such a way that they can come together effectively and at short notice to act as levers for a comprehensive security effect. That is why the work NATO is doing to promote civil-military cooperation is so important. Often called the Comprehensive Approach, such military-led cooperation will need to operate at several levels; the strategic-political, the political-military, at the theater and operational levels, if it is to afford effective counter-terror and counterinsurgency.

Moreover, hybrid warfare does not imply a one-way street for cooperation. Afghanistan and Iraq have demonstrated the extent to which military operations, to have any chance of success, require the political legitimization afforded by coalitions and active civilian involvement. Indeed, the task-list implied by today’s security environment is so long and complex that only with a new civil-military partnership will strategic terrorists be denied bases of operations, and NATO must be front and center of such developments.

Given the insecurity of modern Western society in the face of terror, there is unlikely to be credible power projection without credible homeland protection, and in Europe in particular that can only be afforded through a new and pragmatic homeland security relationship between the EU and NATO, much of which require synergy between criminal and military intelligence through NATO. Equally, the need to project credible military stabilizing power will likely grow and that in turn will require new power partnerships with partner states in Asia (India, Japan and possibly China), Africa (South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya), Latin America (Argentina and Brazil), Australasia (Australia) and, of course, Russia. However, Russia must once and for all decide if it is part of the Alliance’s security mission or a challenge to it. The invasion of Georgia was anti-freedom and NATO must resist such adventurism firmly.

Front and center of Stratcon 2010 must be the modernization and exporting of NATO’s military Standards. Indeed, if transformation is to become smart and move beyond the rhetorical, the Alliance must forge grand interoperability that exports NATO’s way of doing business worldwide to new partners. As part of this drive, NATO Standards will require a new set of civil-military interoperability criteria based on lessons learned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Such partnerships will demand the early involvement in planning of key civilian agencies. Only then will Stratcon 2010 be set firmly on the road to freedom – be it military or civil.

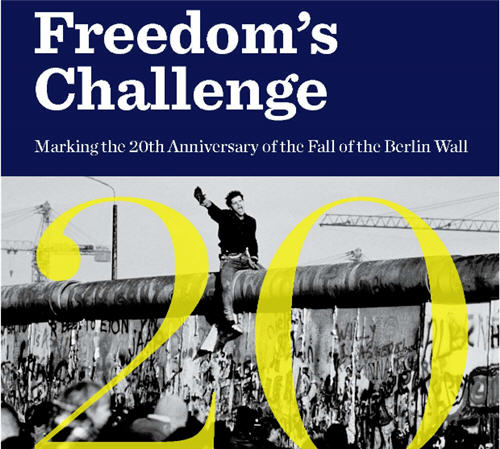

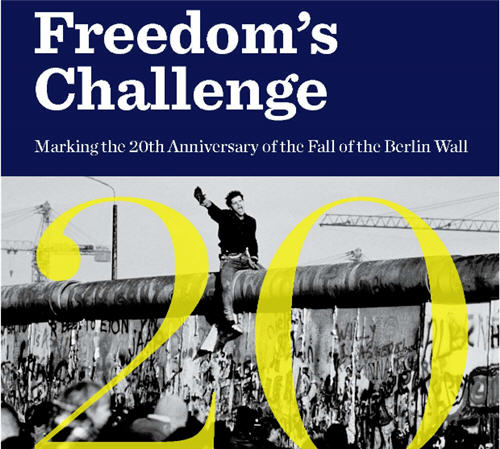

Julian Lindley-French, a member of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Advisors Group, is Professor of Military Art and Science at the Royal Military Academy of the Netherlands.This interview is fromFreedom’s Challenge, an Atlantic Council publication commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.