Syria presents newly minted US National Security Advisor John Bolton with his first foreign policy crisis.

Syria presents newly minted US National Security Advisor John Bolton with his first foreign policy crisis.

On April 9, hours after US President Donald J. Trump vowed Bashar al-Assad’s regime will pay a “big price” for an alleged chemical weapons attack on a rebel-held Damascus suburb, unidentified jets were reported flying over Lebanon and the Syrian news agency said that a missile attack on an air base in central Syria had been thwarted. The Pentagon denied US jets were involved.

Russia and Syria have blamed Israel for the strikes. Israeli officials have declined to comment.

Israel knows its way around Syrian airspace. In March of 2018, Israel publicly acknowledged for the first time that its fighter jets destroyed a clandestine nuclear facility in Syria eleven years ago, which, if completed, would have made Syria the first Arab nuclear state.

Bolton plunged into his new role after his predecessor, Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, stepped down on April 6. He was part of US President Donald J. Trump’s national security team that huddled over the weekend to determine options on how to respond to the alleged chemical weapons attack in Syria. April 9 is Bolton’s first official day on the job.

On April 7, Assad’s military reportedly used chemical weapons in an attack in Douma, a rebel-held suburb of the Syrian capital Damascus. More than three dozen people are believed to have died in the attack.

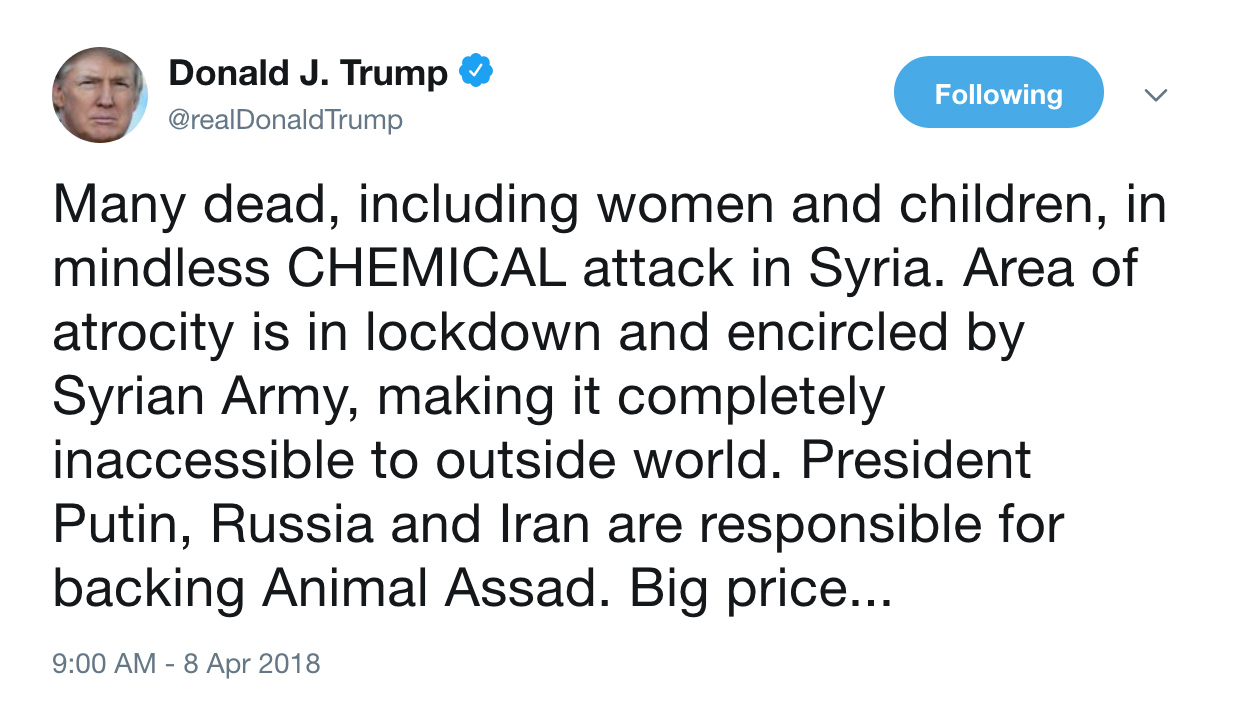

While blame for the attack has not been officially determined, Trump’s tweets on the morning of April 8 suggest that he appeared to believe that this was a chemical weapons attack carried out by the Assad regime.

Trump will find Bolton to be supportive of his views.

Bolton, a former US ambassador to the United Nations, is widely known for his hawkish views on foreign policy, especially on Iran and North Korea.

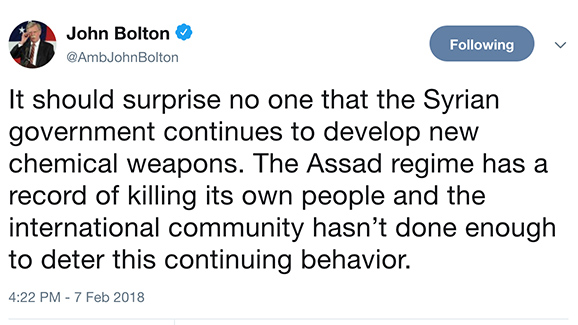

In a Twitter post on February 7, Bolton wrote: “It should surprise no one that the Syrian government continues to develop new chemical weapons. The Assad regime has a record of killing its own people and the international community hasn’t done enough to deter this continuing behavior.”

In his own April 8 tweets, Trump wrote: “President Putin, Russia and Iran are responsible for backing Animal Assad.” This was the first time since his election that Trump has criticized the Russian leader by name on Twitter.

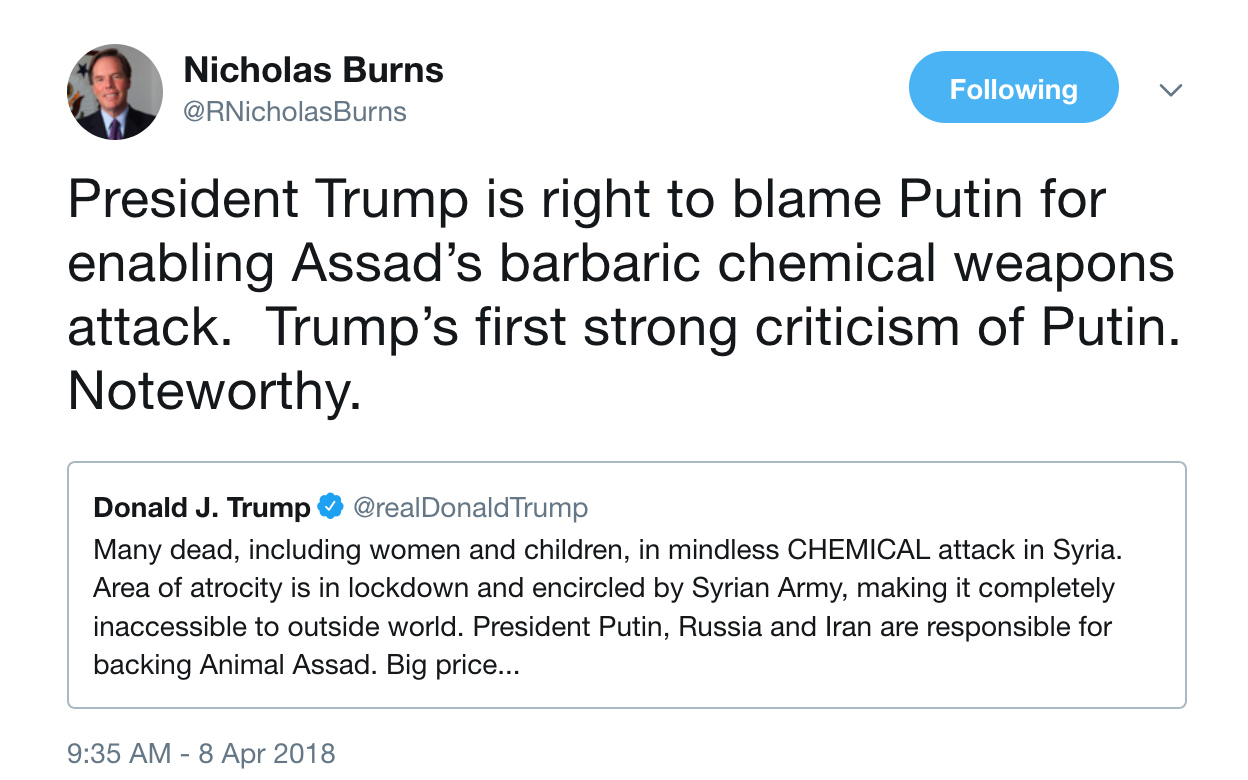

R. Nicholas Burns, an Atlantic Council board member who served as undersecretary of state for political affairs in the George W. Bush administration, wrote in a tweet that Trump’s “first strong criticism” of the Russian president was “noteworthy.”

The attack in Douma occurred days after Trump indicated that he wanted to pull US troops out of Syria.

“President Trump may well want out of Syria, sooner rather than later. But, like his predecessor, he has drawn a chemical weapons red line. And he probably knows what his predecessor learned the hard way: what happens in Syria does not stay in Syria,” Frederic C. Hof, a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, wrote in the New Atlanticist.

“If the reports of deadly chemical usage are accurate, Bashar al-Assad has taken the measure of Donald Trump and has decided he can do what he wants, when he wants, where he wants, and with whatever he wants to whomever he wants,” Hof said. “There is no doubt that the US Department of Defense, reacting to the commander-in-chief’s strong words, has prepared contingency targets for just this sort of circumstance. What must not be left in doubt is the willingness of the United States to match its words with deeds.”

In the past, Trump has followed through on his strong rhetoric on Syria.

A year ago, on April 7, 2017, the US president ordered missile strikes on Syria following a chemical weapons attack on Khan Sheikhoun, a town in the western Idlib province. That attack killed more than seventy people. Many of the victims were children. The Assad regime denied responsibility.

Trump, who at one time opposed bombing Syria, said he ordered the strike because it was in the “vital national security interest of the United States to prevent and deter the spread and use of deadly chemical weapons.”

Fifty-nine Tomahawk Cruise missiles struck Al Shayrat air base, the Pentagon said. The missiles targeted Syrian fighter jets, hardened aircraft shelters, radar equipment, ammunition bunkers, sites for storing fuel, and air-defense systems.

The US intelligence community had made the assessment that chemical weapons were stored at Al Shayrat air base and that aircraft from the base conducted the April 4 chemical weapons attack.

“Trump’s red line was established when he actually struck the regime for its chemical weapons attack about a year ago,” said Faysal Itani, a resident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. “The implication was that if Assad used chemical weapons again, he’d be hit again.”

Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, had famously said that the use of chemical weapons in Syria would be a red line for him, which, if crossed by the Assad regime, would result in a strong US response.

Obama was subsequently criticized for failing to respond militarily after the Syrian regime carried out a chemical weapons attack in Ghouta, an area outside Damascus, in 2013. One of the reasons the former US president was reluctant to act was that he wanted to first get the US Congress on board.

“If nothing happens, Assad will obviously conclude that Trump is as vacuous as Obama when it comes to enforcing threats,” said Itani.

“But if the United States does hit regime targets in a very limited manner, that would not necessarily change the regime’s future behavior anyway,” he added.

Itani pointed out that the United States’ “very limited response” to the chemical weapons attack in 2017 “did not convince [Assad] not to use chemical weapons—instead it showed him the cost of doing so was manageable.”

“The price [for Assad] would have to be big indeed to change that,” he added.

Following the attack in Ghouta, the Obama administration struck a deal under which Syria’s chemical weapons were dismantled and shipped out of the country. However, the deal did not cover chlorine gas, which has been used by the regime in several attacks with deadly results.

There was another catch. Assad did not declare all his chemical weapons.

In his January 5, 2017, exit memo then US Secretary of State John Kerry wrote: “Removing these weapons from Syria ensured that they could not be used—by the Asad regime or by terrorist groups like ISIL—but unfortunately other undeclared chemical weapons continue to be used ruthlessly on the Syrian people.”

This appears to have been the case in Douma on April 7.

“The most important reality here is the military one: Assad needs to take the Damascus suburbs at a minimum cost of (regime) life. One way to break the will of a well-entrenched, stubborn enemy like Jaish al Islam is to use chemical weapons,” said Itani.

“Assad has never stopped using chlorine as a weapon anyway, and never paid any price for doing so,” said Itani. “The larger subtext is of course US policy incoherence and the US president’s consistently signaling his disinterest in the Syrian conflict and eagerness to disengage from it.”

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.