Over the weekend Bangladesh celebrated its 40th year of independence from Pakistan. The Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 is an example of the often contradictory machinations that characterized the Cold War.

The country formerly known as East Pakistan, less than the size of Iowa but with a population greater than, was the epicenter of a global crisis that few recall today.

The much redacted record in the State Department’s Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume XI, South Asia Crisis, 1971, tells a fascinating tale of intrigue and the near start of a nuclear armed conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. The United States and the world began to know of the conflict in East Pakistan through a set of public and private documents such as the Blood Telegram which described the atrocities that were being committed in Dhaka. The news article Genocide written by Pakistani reporter Anthony Mascarenhas in the Sunday Times alerted world leaders of the events and may well have inspired Indira Gandhi to begin “a campaign of personal diplomacy in the European capitals and Moscow to prepare the ground for India’s armed intervention.”

Henry Kissinger, then National Security Adviser to President Nixon, however, saw India as a Soviet client state and its involvement as a potential threat to West Pakistani sovereignty and a blow to US interests. Pakistan was of key importance to the United States because then-President Yahya acted as a channel between the People’s Republic of China and the United States. Kissinger saw the Chinese as a vital potential ally for the United States and as “a decisive restraining influence on India” and ultimately the Soviet Union.

To show US sincerity in maintaining a relationship with the People’s Republic, Kissinger went as far as to suggest to Ambassador Huang Hua, that “if the People’s Republic were to consider the situation on the Indian subcontinent a threat to its security, and if it took measures to protect its security, the US would oppose efforts of others to interfere with the People’s Republic. We are not recommending any particular steps; we are simply informing you about the actions of others.”

Kissinger and Nixon knew particularly well what that statement meant as two days later they privately discussed the possible response by the United States if the Soviets moved against the People’s Republic of China. The following exchange, pregnant with meaning, between the two men is extraordinary:

“Kissinger: ‘If the Soviets move against them [the Chinese] and then we don’t do anything, we’ll be finished.’

Nixon asked: ‘So what do we do if the Soviets move against them? Start lobbing nuclear weapons in, is that what you mean?’

Kissinger responded: ‘If the Soviets move against them in these conditions and succeed, that will be the final showdown. We have to—and if they succeed we will be finished. We’ll be through.’”

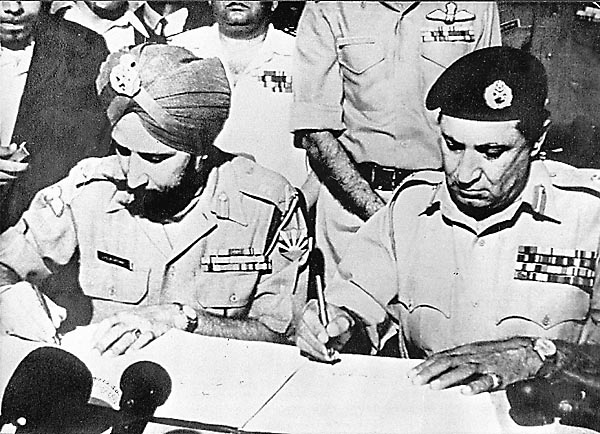

Ultimately, the PRC informed the Nixon administration it had no intention of starting a conflict and India chose not to go beyond East Pakistan in its war with Pakistan. A nuclear armed conflict between the two super powers was averted and a small nation gained its independence.

So, as Bangladeshis celebrate their 40th year of freedom, perhaps we too should celebrate their independence and the unimaginable war that didn’t happen.

Mahbub Sarwar is with the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council.

Image: bangladeshindependence.jpg