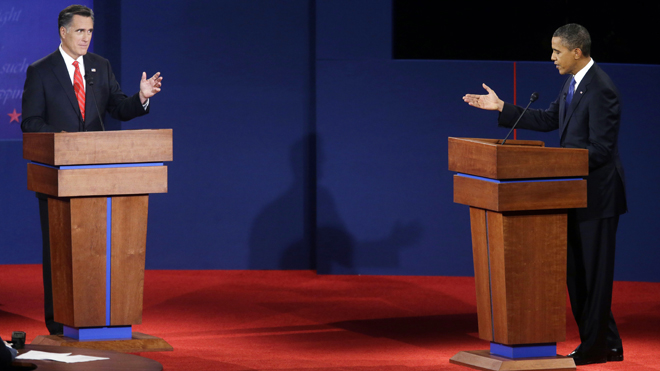

President Obama and Mitt Romney will battle over foreign policy in tonight’s third and final presidential debate. No matter who wins the presidential election November 6, Mr. Romney or Mr. Obama will have to confront five urgent national security issues in the first weeks of his term.

Neither of the two candidates has thus far articulated a clear strategy and detailed plan for how to tackle them. This is understandable for keeping options open during an electoral campaign. But once the dust settles, all five issues will require determined presidential leadership to safeguard the security and well-being of the American people.

1.Come back from the fiscal cliff and shrink the debt

This is as much an issue of national security as it is domestic economics. The world still depends upon American leadership, which tips the scales in favor of freedom, democracy, market economics, human rights, and the rule of law. This role is especially important when a range of actors – Islamist extremists to authoritarian capitalists – is trying to tip the scales the other way.

Leadership requires the ability to make choices and back them up with resources. But shrinking budgets, big deficits, looming debt, and a weak economy mean Washington has no resources to spare. America’s fiscal situation diminishes options and saps public confidence. This leads us to eschew involvement in serious crises such as Syria, or retreat from military operations even without success.

As long as every new dollar spent is a dollar borrowed, we will not apply resources strategically. To prevent the markets from swinging wildly, the lame duck session of Congress in December needs to extend the deadlines for sequestration (automatic spending cuts set to begin taking effect Jan. 1) and for when the Bush-era tax cuts (and other tax breaks) expire. Such a move would buy the new president and Congress time – say, three months – to submit a serious long-term debt-reduction plan.

The key components of such a plan are already well-known: reforming the big-ticket items of Social Security and Medicare, so they do not present enormous and unlimited liabilities, and capturing greater tax revenue by simplifying and reforming the tax code. Other cuts to domestic spending and defense can help, but the math will never add up without the big-ticket changes.

2.Reinvigorate the international economic order

If getting America’s fiscal house in order is about US competitiveness, strengthening the global economic system is about leveling the playing field on which we compete. As new economic powers such as China, India, and Brazil have risen in the world, challenges to the foundations of the liberal economic order have grown. For one, major state-run or state-subsidized enterprises have become dominant players in much of the world, especially in the energy sector.

Monetary policy and non-tariff regulations have been employed to tilt the trading playing field. Intellectual property is often not protected effectively. Poor labor and environmental conditions in some countries have contributed to jobs flowing there from more developed countries with higher standards, while exerting downward pressure on wages on those jobs that remain.

These are not new phenomena. What is new is the lack of determined leadership from the developed economies to reinforce the global economic order that has produced the very opportunities developing nations are now exploiting. Today’s rising economic powers are themselves changing over time – aging, moving into higher tech- and service-driven industries, increasing their interdependence within the global economic system, even reforming politically.

As a result, their interest in a well-functioning liberal economic order is rising. The next US administration needs to use a combination of penalties and opportunities: tougher counter-measures on unfair trade, labor, and currency practices where they exist, particularly through the World Trade Organization, while simultaneously renewing a drive toward freer global trade.

3.Deal with the Iran nuclear challenge

Both the Bush and Obama administrations have pursued a policy of UN resolutions, sanctions, and negotiations in an effort to stop Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon. But Iran has not complied with international demands that it halt uranium enrichment. This is a problem not only because the Iranian regime has proven itself a regional hegemon, a supporter of terrorism, and an existential threat to Israel. If Iran acquired a nuclear capability, that would also likely lead to a regional nuclear arms buildup.

Mr. Obama and Mr. Romney both promise to continue down the same path: tighten sanctions, while keeping “all options on the table” – i.e., including military. That posture is appropriate for election season, but in the months after the election, the president will have to make a choice.

Will America and its allies use coercive force to destroy as much of Iran’s nuclear program as possible, accepting the consequences of possible retaliation? Or will we stand by as Iran moves toward acquiring a nuclear weapon?

If Israel launches military strikes on Iran, the region risks breaking out in conflict and accelerating further nuclear proliferation. If Washington chooses to pursue a military option, the president will need to gain the support of allies and manage the global political consequences of such a step.

4.Prevent a collapse in Afghanistan

During the campaign, both Obama and Romney have stood by the 2014 deadline for transition in Afghanistan, though Romney has said he would reassess the need for troops based on conditions at the time. Once the election is past, however, the president will need to face the reality that the situation in Afghanistan is declining rapidly. The deadline itself – and statements such as “We will be gone, period” – have encouraged the Taliban, while signaling to the local population they need to accommodate the Taliban in preparation for an American exit.

“Green-on-blue” attacks (Afghan security forces attacking US forces) have shattered trust. The Afghan national security forces do not have the capability to maintain security throughout the country without direct US engagement, and it is unlikely they will have that full capacity by 2014 either. The Afghan national election scheduled for 2014 risks becoming a catalyst for a crisis of governance and fragmentation of the country – precisely at a time when the United States and others will not have the forces in place to keep a lid on upheaval.

A governance and security collapse in Afghanistan would likely bring the Taliban back to power in at least the south of the country, and open up a contest for Kabul and the country as a whole. This would be a catastrophe for human rights, especially women’s rights and children’s education. It would also be a victory for violent Islamist extremists, raise the prospect that Afghanistan could again be a safe harbor for Al Qaeda, and further destabilize Pakistan.

Rather than stick stubbornly to a 2014 deadline and risk losing everything America and coalition forces have fought to achieve in the past 10 years, the president will need to assess the situation and be open to revising the withdrawal plan and timeline. And he’ll need to communicate that commitment to Afghans – and the Taliban.

Many elements of current US policy should continue: a reduced US military footprint, with more support for local security forces; support for good governance, education, women’s rights, and economic development; and help in fighting corruption. More effort needs to go into political reform to give Afghans greater confidence in their leaders. This may mean greater emphasis on local empowerment. Once conditions are stable, a US withdrawal will still be possible, but we can only get there if we drop the idea of a strict deadline.

5.Save Syria and the Arab Spring

As many as 30,000 people may now have been killed in Syria, while the great democracies of the world have stood on the sidelines. The Bashar al-Assad regime is willing to kill as many people, for as long as it takes, in order to stay in power. The only way forward is for this regime to be defeated. Others – Iran, radical Sunni extremists, Al Qaeda, even Russia – have stepped in for their own darker reasons.

With almost no practical support from the West, what began as lofty aspirations by the Syrian people for a more democratic and just government have been hijacked in part by other forces in the region. Whether driven by a humanitarian impulse to stop the mass killing, a national interest in preventing wider conflict in the Middle East, or a strategic move to blunt Iran’s influence in the region, US involvement and leadership will be critical in building an international coalition to address the Syrian crisis.

The Arab Spring has proved to be the most significant political and security development in the world since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Yet America scarcely treats it as such. The call for greater democracy and justice in the Arab world should be music to American ears. After decades of tyrants who ran corrupt and oppressive systems, scape-goated the United States and Israel, and inadvertently created radical Islam as their main source of opposition, the people of the Arab world are demanding change.

As messy and risky as this transition is proving to be, greater democracy, opportunity, development, and justice in society is the only remedy for the ills plaguing the broader Middle East, and in turn plaguing the world. The United States has been far too timid in offering assistance to real reformers in the Arab world, while simultaneously far too passive in countering the impact of violent extremists. Drones are handy for taking out key terrorist leaders, but not a substitute for a wider policy.

The policy must include bold support for freedom, democracy, tolerance, and good governance, backed up by substantial US assistance, including security assistance, to those who share these goals. At the same time that policy must reduce assistance to governments that do not share these goals. And America must maintain a relentless focus on disrupting terrorist groups throughout the region.

Kurt Volker is executive director of the Arizona State University’s McCain Institute for International Leadership, based in Washington, D.C., with a presence on ASU’s Tempe campus. He is also a senior fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a member of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Advisors Group. He is a former US Ambassador to NATO. This piece was originally published on The Christian Science Monitor.

Image: Romney%20Obama%20Debate%20Main.jpg