“Russians really aren’t the heart of our problem,” former CIA Director Michael V. Hayden said at a conference hosted by the Atlantic Council in Washington on October 3. Speaking on Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election, Hayden noted that he does not believe that the interference had an impact on the result and that anti-disinformation measures are just “a painkiller. The fundamental fix is who are.” He emphasized that leaders need to focus not only on security, but also on doing their “duties as citizens… to help contribute to the long-term solution: which is fixing ourselves.”

Hayden spoke at the Atlantic Council’s Global Forum on Strategic Communications and Digital Disinformation (StratComDC), a two-day conference convening global leaders in combatting disinformation and securing digital infrastructure.

Hayden, a retired four-star general in the United States Air Force, director of the National Security Agency under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, and Director of the Central Intelligence Agency under Presidents Bush and Barack Obama, explained why the intelligence community and government failed to protect against Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, and what needs to be done fixed to prevent foreign interference in the future.

For his talk closing #StratComDC, @GenMhayden says he’ll approach his talk as an intelligence officer: “The Russians did it…to mess with our heads ✅ …to Punish Hillary Clinton because [Putin] hates her ✅ …to invalidate & delegitimize the inevitable President Clinton ✅…” 2/ pic.twitter.com/2isRvSia05

— Atlantic Council (@AtlanticCouncil) October 3, 2018

Cyber dominance vs. information dominance

For Hayden, “one of the reasons my tribe – the intelligence folks – were a little bit late” in responding to the Russian interference was “the lens we had chosen for ourselves prior to now to look at what the Russians did.” It started all the way back in the 1990s, when intelligence and military officials had a “doctrinal debate” on how to respond to the growing digital space and the unique threats it could bring. The central question was whether the United States would be “in the cyber dominance business or the information dominance business,” Hayden explained. Ultimately, Washington decided to “put our weight in cyber dominance,” in part because “that information dominance thing looked really complicated – the cyber thing was bad enough” and because the United States’ emphasis on the freedom of speech and due process meant that information dominance was “not a comfortable field for Americans to play in,” according to Hayden.

Russia, on the other hand, did not face such constraints and therefore “went to door number two”: information dominance. Moscow began to effectively weaponize information to achieve its foreign policy aims, such as when its media tools sowed doubt about Russian responsibility for the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 in 2014. The real test for the Russians, however, came in 2015, when bots and online activists were able to promote a conspiracy theory in Texas that federal authorities were using military exercises to disguise the detention of domestic political opponents. The Jade Helm incident, as it became known, even caused the governor of Texas to mobilize state troops to monitor the activity of the federal authorities. The wild success of this conspiracy, Hayden said, allowed the Russians to “make a decision at the operational level that we can play with these guys.”

‘Slow to warn’

Once Russian online actors began impacting the US presidential election, both through the promotion of fake news and the “hack and dump” of files from the Democratic National Committee, Hayden conceded that the intelligence community did not move fast enough to address the threat. “There is good evidence that the intelligence community was… slow to warn” policy makers of the danger, mainly because, Hayden argued, “there was an evolution in the intelligence community’s understanding of what it was the Russians were doing.”

It was true that “the intelligence guys were a little late grabbing the administration by the lapels,” Hayden said, but equally “the policy guys were also late to respond.” The political ramifications of exposing the Russian activity during the final stages of the campaign weighed heavily on the Obama administration, and curtailed its willingness to sound the alarm. As intelligence officials, Hayden conceded, “when you go in there with something that is not going to make the president’s day, that is going to cut across his policy, preferences, or his politics, it just takes you longer to convince him.”

This problem became more acute with the inauguration of US President Donald J. Trump, who “because many Americans were using this [interference] narrative to de-legitimize his election, refused to embrace this [evidence of] interference,” according to Hayden. This led Trump administration officials to “promptly lie” about what intelligence officials told Trump about Russian interference in the election and caused a “reluctance on the part of this administration to hug the problem and do something about it.”

Eventually, Hayden described, there was a “plea by the outgoing and incoming commander of US cyber command to take the handcuffs off. . . for a regime of law, policy, and guidance that would allow the fairly routine exercise of digital power above the threshold of traditional espionage but below the threshold of any generally accepted definition of armed conflict.”

The new Trump administration’s top cyber officials continued to demur on taking these steps, but that has changed with the arrival of John Bolton as the new National Security Advisor. As Hayden explained, “Ambassador Bolton [has] made a point to lean in the direction” of “actually using the cyber weapon to deter behavior.” There is no real way to defend against the types of disinformation campaigns launched by Russia in a technical way, Hayden said, but the key is “dissuasion, not defense. This is about punishment. This is about punishment or the threat of punishment.”

‘A post-truth world’

Hayden described the problem of disinformation and digital interference as a “three-layered cake,” where “Russians are the top layer.” It may be the most visible, but it is also the smallest and least vital to the structure. The bottom layer, Hayden said, “is us.”

“We are drifting as a society into what can be fairly described as a post-truth world,” Hayden said, where there is no longer a basic understanding of what objective facts are. The Russians did not create this, but simply came “in over the top and [took] advantage.” To launch a successful interference or disinformation campaign, Hayden said, “you never create a division in a society, [rather] you identify and exploit pre-existing conditions.” The Russians, Hayden explained, “tried this on the Norwegians too. It didn’t work – because they are not the same society that we are.”

The United States’ “post-truth” environment was made worse by Trump, Hayden’s second layer in the disinformation cake. As a candidate, Trump “recognized” the post-truth layer “and ran on it,” according to Hayden. It was now up to institutions that were “fact-based,” such as “the intelligence community, law enforcement, scholarship, science, and journalism,” to “push back against a norm-busting administration without busting their own norms,” Hayden argued.

Closing his session in front of an array of government officials, intelligence officers, and security experts, Hayden said the first duty of those collected was “to buy wiser people than ourselves the time and space to fix the fundamental problems.” But in these trying times, it was equally important that they do their “duties as citizens… to help contribute to the long-term solution: which is fixing ourselves.”

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

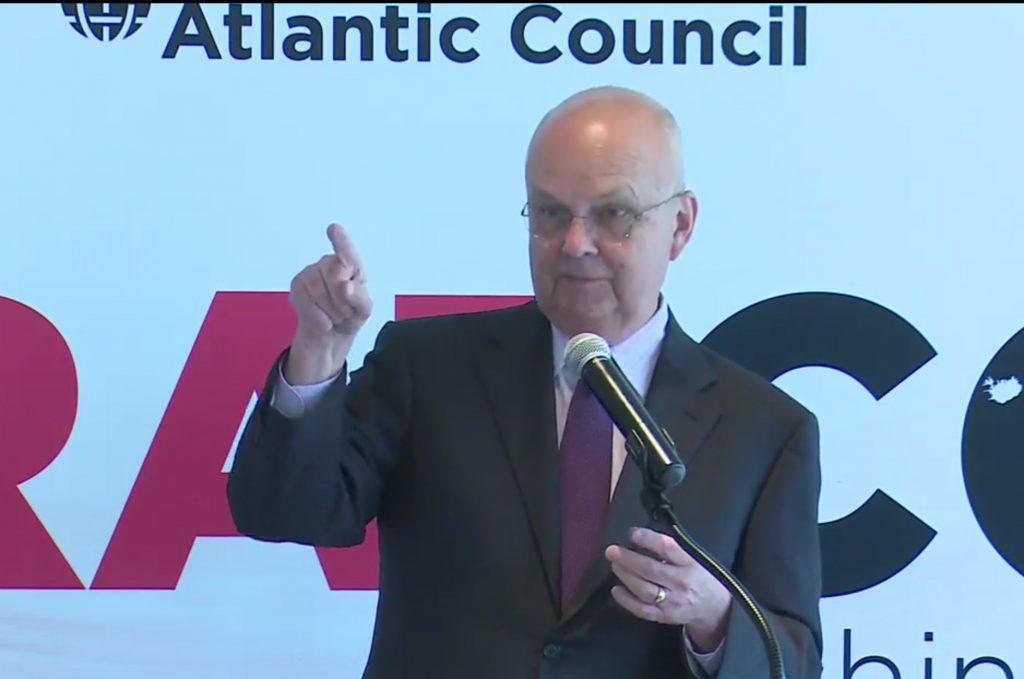

Image: Retired Gen. Michael V. Hayden, who served as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency from 2006 to 2009 and the National Security Agency from 1999 to 2005, addressed the Global Forum on Strategic Communications and Digital Disinformation (StratComDC) in Washington on October 3. The two-day event was hosted by the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center in partnership with the Embassy of Sweden, Lithuania’s Foreign Affairs Ministry, the United Kingdom’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and Twitter.