The unfolding Euro crisis has raised a new variant on the old German Question. For much of its history as a state, Germany has been the pivotal state in Europe. After the Cold War and the reunification of East and West, the fate of "Europe" as a unified political and economic space depended entirely on Germany’s willingness to let go of the vaunted Deutsche Mark. Now, the fate of the Euro — and arguably the EU — rests on Angela Merkel.

Berlin has, naturally, been pushing fiscal austerity throughout the current financial crisis and recession, agreeing to various bailouts and stimulus packages after kicking and screaming in resistance. Keeping with the script, they have been very reluctant to help out the Greeks, who they see as having gotten themselves into a financial mess with profligate spending and a poor work ethic. (Greece’s early retirement age is apparently especially grating, as it’s constantly cited by German commentators.)

And, certainly, German domestic politics are not likely to sway Merkel to change course. Spiegel:

Fully 71 percent of Germans are against sending EU funds to Greece, according to a survey by the research group Emnid. A survey conducted for the tabloid Bild am Sonntag found that just over half of Germans would like to see Greece thrown out of the euro zone altogether.

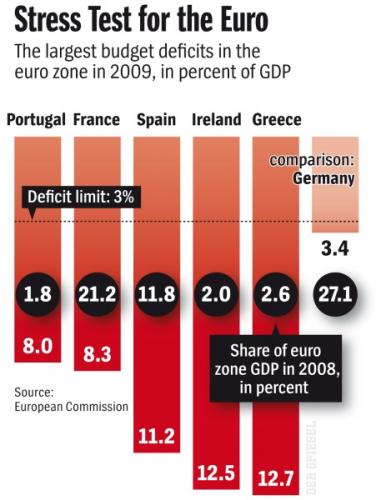

Nobel economic laureate Paul Krugman has been arguing for weeks that the problem is not mainly Greek — Spain, with a much bigger economy, is having quite serious issues of its own — nor mainly one of a "lack of fiscal discipline" on the part of some irresponsible governments.

Nobel economic laureate Paul Krugman has been arguing for weeks that the problem is not mainly Greek — Spain, with a much bigger economy, is having quite serious issues of its own — nor mainly one of a "lack of fiscal discipline" on the part of some irresponsible governments.

No, the real story behind the euromess lies not in the profligacy of politicians but in the arrogance of elites — specifically, the policy elites who pushed Europe into adopting a single currency well before the continent was ready for such an experiment.

Spain, in Krugman’s view, was the classic case of a bubble economy while, yes, Greek’s government was irresponsible. But the problem now is that their hands are tied. They’ve got neither the flexibility that comes with having independent control of one’s own currency nor the security that comes with being a failing region within a sovereign state.

None of this should come as a big surprise. Long before the euro came into being, economists warned that Europe wasn’t ready for a single currency. But these warnings were ignored, and the crisis came.

Now what? A breakup of the euro is very nearly unthinkable, as a sheer matter of practicality. As Berkeley’s Barry Eichengreen puts it, an attempt to reintroduce a national currency would trigger “the mother of all financial crises.” So the only way out is forward: to make the euro work, Europe needs to move much further toward political union, so that European nations start to function more like American states.

Which, as my colleague Fran Burwell, the director of our Transatlantic Relations program, reminds us, was the whole point behind the Euro to begin with: It was first and foremost a tool for political integration. But the Economist‘s EU columnist, Charlemagne, thinks it may be time to rethink that goal.

I think the siren lure of economic logic is blinding a lot of people to the political realities of this crisis. There is no doubt that it was a big risk to launch a monetary union, 11 years ago, without an economic union on top of it, to organise fiscal transfers between different corners of the union that diverged too far from each other.

[…]

But as I have said before, over the past five years of watching politicians in Brussels, I have watched the direction of EU travel head firmly away from closer federal integration, and towards a messy sort of intergovernmentalism, in which a handful of big countries increasingly call the shots.

[…]

I don’t think a Greek default is a big enough crisis to change the political weather in the EU: Greece represents a tiny sliver of union GDP.

[…]

I note that bailing out Greece is already proving so politically painful for leaders like Mrs Merkel that she would not tolerate any discussion of how such a bailout might take place, at the February 11th summit. It is interesting to note that allies of Mrs Merkel are currently spinning away like mad that any rescue would absolutely not be a free gift for Greece, but would only happen after Greece had undertaken fantastically painful cuts.

[…]

But the underlying political lesson is still clear enough: this stuff is toxic politics. And any hint of establishing a mechanism for the systematic rescue of a country under attack would be still more toxic. And that is what Prof Krugman is talking about when he talks about fiscal integration.

And a golden lesson of politics is: political leaders only do really hard and painful things when they absolutely have to. Until then, they would much rather fudge things.

But George Mason political scientist Henry Farrell disagrees.

Saying that politicians will want to muddle through is stating the obvious – but the point is that muddling through is not a sustainable long term strategy. Either the muddling through will be insufficient, in which case EMU will finally succumb to one of the succession of crises that will almost certainly result, or it will be sufficient, in which case it will serve as the basis for a long term shift in the economic governance of the Eurozone towards coordinated fiscal policies and some degree of fiscal transfers in times of crisis, and perhaps more than that.

[…]

This will almost certainly culminate in a set of general institutional mechanisms which applies to all the eurozone countries, including both those countries at risk of default and those which are highly unlikely to get into trouble. That’s the way that the EU works – and this will be a quite significant step towards further integration. Of course – the rescue effort may fail (for example, Germany and Greece’s current spat may reflect irreconcilable political differences) – but if it does fail, so too will the euro project.

The hope of fans of a united Europe is that the Germans will come to the same conclusion and decide that failure is not an option. That is, after all, what Merkel did with the financial crisis — ultimately approving the German stimulus package that she’d spent months fighting against.

But will she feel the same pressure to swallow her principles for Europe? Let alone for Greece? With 70 percent of her own voters opposed? It’s by no means certain.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. Photo: AP. Chart: Spiegel.

Image: merkel-greece-question.jpg