Many view China’s Belt and Road Initiative as the most geoeconomically significant infrastructure project since the Marshall Plan. Promising alternative trade routes, abundant capital flows, and advanced infrastructure to the developing world, the program has scaled significantly since its inception in 2013.

Standing at the crossroads of Eurasia, the Arab Gulf states and broader Middle East are an important link between the economies of East Asia and Western Europe.

Yet the region’s chronic and destabilizing conflicts pose a challenge for Beijing, which has distanced itself from entangling alliances outside its core periphery. In the Middle East, China will find it much harder to invest neutrally, especially within the context of the Saudi-Iran conflict and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) dispute. In the case of the former, China is Tehran’s key economic benefactor, with sanctions now being re-imposed. With Iranian oil locked out of European and US markets, the country’s reliance on China and India has been exacerbated.

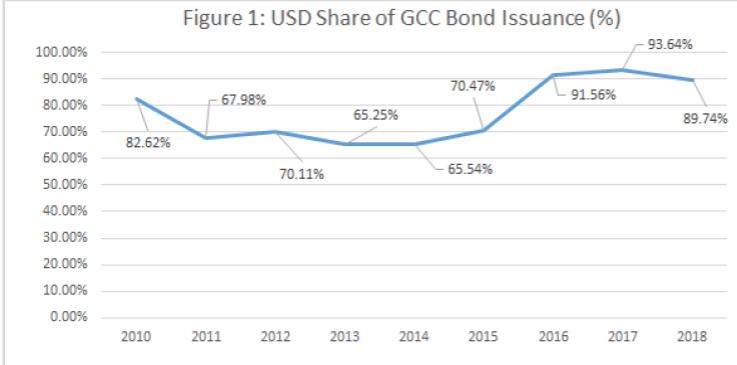

Observers in Riyadh are not oblivious to this as they structure their own international dealings. In regards to international debt, Gulf issuers seem to reflect this divide. While the US dollar is the dominant currency choice in the region (Figure 1), the Saudis are typically regarded as the largest benefactors of the dollar in the Gulf.

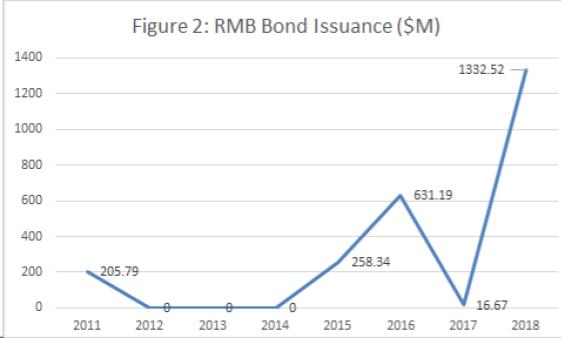

At the same time, Renminbi (RMB)-denominated issuance in the Gulf hit a record high in 2018 (Figure 2). These levels exceed the previous heights seen in 2015 and 2016 at the apex of RMB internationalization. Within these flows, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the largest issuer of RMB debt, followed by Qatar.

In spite of Abu Dhabi’s alignment with Riyadh’s hardline policy on Iran, prominent Emirati banks, specifically Emirates NBD and First Abu Dhabi Bank, have led the country’s issuance in RMB bonds. Most recently in 2018, the Emirate of Sharjah issued an RMB-denominated international bond, suggesting more flows to come in the future. In the past, governments like Hungary and Poland have used these bonds symbolically to expand trade relationships and curry favor with Beijing.

Though Doha currently lacks such sovereign issuance, it was the home of the first RMB clearing hub in the Middle East. Since then, Dubai’s RMB clearing has grown significantly, with Saudi Arabia and the UAE having much more at stake with Chinese trade than Qatar. Looking at trade volumes, Doha’s power play in LNG, as opposed to oil, has cultivated a broad market of consumers across Northeast Asia, including Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, beyond Beijing’s reach.

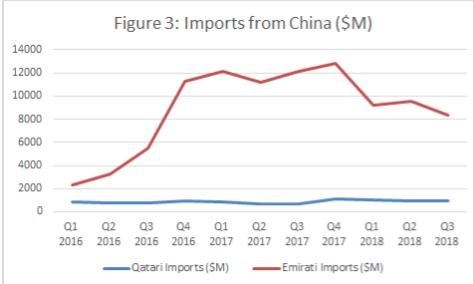

The existence of this facility should not overshadow the data, which suggests that the UAE and Saudi Arabia have much more at stake with Chinese trade than Qatar. Looking at trade volumes, Doha’s power play in LNG, as opposed to oil, has cultivated a broad market of consumers across Northeast Asia, including Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, beyond Beijing.

In the UAE, while exports have grown marginally, the countries’ import volumes have been on a tear (Figure 3). While Qatar runs a moderate surplus with China, the Emirati bilateral deficit with Beijing has widened considerably in the past two years, with imports nearly twice the size of exports in the latest reporting period.

Moving forward, China is likely to deepen economic relations in the region with players that are already neutral or have little political baggage associated with them. Prior to the GCC dispute of 2017, Qatar was widely regarded as a neutral hub, with little political risk, making it an ideal spot for the RMB hub when it was first established. Today, Kuwait seems to fit that label better, reflecting the country’s efforts to defuse the GCC dispute in the past year.

The Kuwait Silk Road Fund, a $10 billion partnership between China and Kuwait to invest in local projects, may likely serve as a model, albeit an optimistic one, for future interactions. As part of the arrangement, China pledges to cooperate on debt financing with strategic partners in the country, potentially raising the financing capacity as high as $30 billion. It is likely that a significant portion of this debt will be RMB-denominated, potentially supporting the role of the currency in the region.

The choice of Kuwait supports the thesis that China will likely pick and choose its relations in the Gulf, wary of miring itself in regional politics. Riyadh, in particular, may prove to be a thorny partner for Chinese investment, as the country has been eager to flex its economic muscle in the past.

The pressing issue for Beijing will be the need to balance political risk exposure with tangible economic benefits. Though the UAE may feature some similar political concerns as Saudi Arabia, its prominent role in regional finance will necessitate cooperation to some degree. Kuwait, though politically immunized, plays a small role in regional economics, in spite of the Kuwait Investment Authority’s size. As the GCC dispute pares back, Doha could very well prove itself to be a happy medium between the two.

Michael B. Greenwald is a fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. He is deputy executive director of the Trilateral Commission, senior adviser to Atlantic Council President and CEO Frederick Kempe, and adjunct professor at Boston University. From 2015-2017, Greenwald served as the US Treasury attaché to Qatar and Kuwait. He previously held counterterrorism and intelligence roles in the US government.

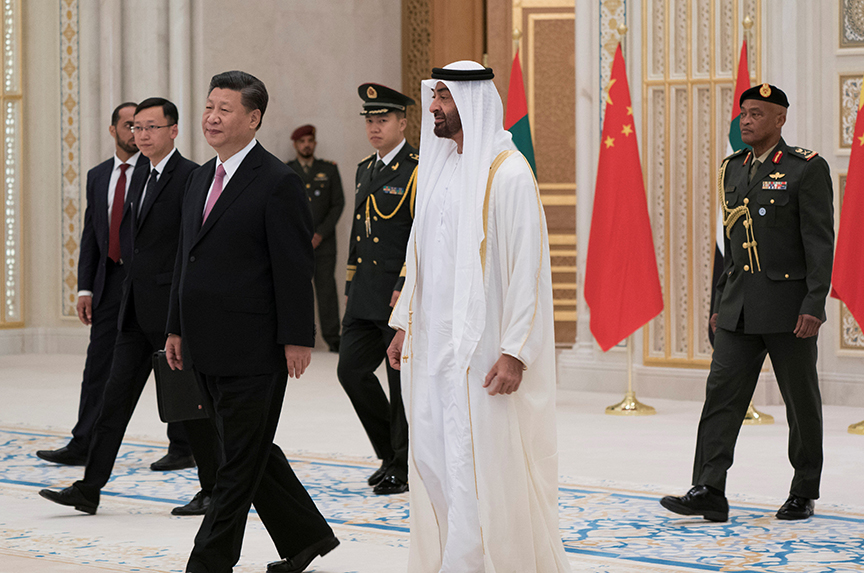

Image: Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan walked with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Presidential Palace in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, on July 20, 2018. (WAM/Handout via Reuters)