The US needs better tools to fight transnational repression. Here’s where to start.

The alleged plan was brazen: Snatch prominent Iranian-American dissident Masih Alinejad from her Brooklyn home and transport her on a military-style speedboat to Venezuela for rendition to Iran, where she would likely face imprisonment, torture, and perhaps even execution.

On July 13, the US Department of Justice unsealed a federal criminal indictment charging five Iranian nationals—four of whom are based in Iran and one in California—as part of a conspiracy to kidnap Alinejad. But however shocking, the plot surprised few observers who have followed the Islamic Republic of Iran’s decades-long campaign of hunting down dissidents abroad—a tactic now employed by many other modern authoritarian regimes.

That such a plan was partially executed on American soil against a US national highlights the urgent need for legal tools to combat the worsening trend of transnational repression around the world. As autocrats grow increasingly bold, the United States must meet the challenge by preparing effective, forward-thinking policy.

A growing global tendency

Regimes target exiles and diaspora communities in many ways, including through surveillance—such as the use of Israeli spyware Pegasus to monitor exiled journalists and human-rights defenders—and the harassment and imprisonment of exiles’ family members who remain in the country of origin. Renditions and assassinations are among the most serious forms of transnational repression.

In the Iranian context, they are carried out with alarming frequency. According to ongoing research conducted by the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center, a non-profit organization that documents extrajudicial killings, the government is suspected to have killed or disappeared more than five hundred actual or perceived dissidents across more than twenty-five countries. Iraqi Kurdistan was the scene of the most killings and disappearances, with 380 reported cases, followed by the rest of Iraq, Pakistan, and Turkey. In Europe, France leads with thirteen, and six have been killed in Germany.

While Tehran’s campaign of extraterritorial assassinations has existed since 1979, the practice of kidnapping activists and sending them back to Iran has ramped up in recent years.

Before the plot against Alinejad, Rouhollah Zam—a dissident Iranian journalist with French residency who founded a Telegram channel used to organize popular protests—was lured to Iraq by agents from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, then abducted and brought to Iran, where he was executed in December 2020 after a trial widely characterized as unfair. California-based Jamshid Sharmahd, a German citizen who holds US residency, was seized during a stopover in Dubai in July 2020 and taken back to Iran, presumably in retaliation for his involvement with an Iranian opposition group. Currently detained in an undisclosed location with no access to counsel of his own choosing, his heath is deteriorating.

But the Iranian state is far from the only one resorting to such tactics. A February report by watchdog Freedom House found that governments in thirty-one “origin countries” have targeted exiles in seventy-nine “host countries.”

Extreme examples, such as the brutal 2018 murder of Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi, the state-ordered nabbing of Belarusian activist Roman Protasevich off a Ryanair flight, and the kidnapping attempt on Alinejad, command global headlines. But these have quieter effects on dissidents and diaspora communities more broadly, leading them to silence themselves for protection. Self-censorship is detrimental to the free flow of information, as well as to the defense and promotion of the freedom of expression, association, assembly, religion, and other internationally recognized rights.

Thanks to improvements in technology and the widespread nature of social networks, activists forced into exile can still mobilize populations at home through compelling information campaigns. To authoritarian regimes—and even ostensible democracies with authoritarian tendencies—this is a threat. A generation ago, the Islamic Republic focused on eliminating the vestiges of the deposed Shah’s government and other political opposition abroad. Today, its hit list includes savvy activists capable of leading social media movements (Alinejad) or creating tools to mobilize populations (Zam).

Bad international actors must be made to believe that the cost of engaging in transnational repression is too high. Holding them accountable, as well as regulating the private companies selling spyware which enables this abuse, are two options. But a major barrier to accountability is the “transnational” nature of these crimes: Criminal and civil legal tools are often constrained because of borders and national sovereignty.

These barriers demand the creation of new laws, or the repackaging of existing laws, to address this alarming trend more effectively.

The limitations of current policy

The United States recently offered a useful example. In February Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced the so-called Khashoggi Ban, which he said allows authorities to impose visa restrictions on anyone “believed to be directly engaged in serious extraterritorial counter-dissident activities,” on behalf of a foreign government. In crafting the measure, the State Department relied on existing tools such as travel bans—but did so while also shining a light on this particular type of malign activity.

Still, the Khashoggi Ban stops short of freezing assets and lacks a mechanism for enforcing accountability. That’s why it has been supplemented by a patchwork of legislative proposals in Congress.

Those include the Protection of Saudi Dissidents Act of 2021, which proposes prohibiting US arms sales to Saudi Arabia for as long as the government is engaging in transnational repression against dissidents, and the Transnational Repression Accountability and Prevention (TRAP) Act, which targets the abuse of INTERPOL by strengthening transparency and liability within the organization.

These measures reflect the divergence in approaches when it comes to countering transnational repression.

Governments in origin countries make use of a globalized system of finance and travel to facilitate their plans, as well as spyware and surveillance firms to mark and track their targets. But that’s where the commonalities end: When it comes to fighting cross-border persecution of exiled dissidents and diaspora communities in the United States, the risks and tools to combat the problem often differ depending on a country’s relationship with Washington.

For example, allies may be able to exert influence at universities and other institutions, in addition to deploying diplomats to implement their plans. Agents of the state may even formally register their activities under the Foreign Agent Registrations Act in a seemingly innocuous way while pursuing more nefarious goals. Existing legal tools may be insufficient to address the actions of allies, which may be covered by sovereign immunity or other mechanisms unavailable to countries that are targeted by sanctions, terrorism designations, or other forms of accountability.

Alternatively, Washington may have less leverage with non-allies because it would be unable to offer various incentives, making their plans harder to foil. Limited diplomatic relations may also mean that perpetrators will never be extradited to the United States, while individual defendants (and those complicit) may not have to face civil suits.

This is why it’s imperative to listen to voices from civil society and those working closely with dissidents to craft policies and legal tools that can take aim at these unique threats.

Tools for criminal accountability

Fighting transnational repression should start with defining, in clear legal terms, exactly what it is.

A comprehensive definition introduced through legislation could allow prosecutors to target perpetrators more directly, instead of relying on charges such as conspiracy to commit bank and wire fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering—which are respectively Count Three and Count Four of the unsealed criminal indictment in the Alinejad case. While the first paragraph of the indictment identifies the problem as one of transnational repression, the lack of a specific provision in the US Code means the defendants needed to face disparate charges.

The four Iran-based defendants were charged in federal court because they hired a private investigative firm based in the United States and used the US financial system, which is prohibited to agents of the Islamic Republic. But many other acts in the lead-up to the kidnapping plot encompassed transnational repression. For instance, Iranian officials pressured Alinejad’s relatives—and even offered payment—to entice her to meet them in a third country, where she could be more easily abducted. They also arrested her apolitical brother and sentenced him to eight years in prison on a raft of national-security charges, which critics say were intended to penalize him for simply being her brother and unwilling to betray her.

These are all acts of transnational repression intended to target a US person, but they do not fall neatly within existing US criminal law.

The definition of “transnational repression” provided by US officials is broad but provides a foundation for further development. The TRAP Act, for one, defines the term as “efforts by foreign governments to pursue, harass, or otherwise persecute individuals for political and other unlawful motives overseas, and for other purposes.”

A new legal definition could specifically outline what types of acts will constitute harassment and persecution—including crimes like murder, torture, and kidnapping, as well as the spread of disinformation, cyberattacks, and the abuse or misuse of international law enforcement tools such as INTERPOL Red Notices.

As lawmakers consider new legislation criminalizing transnational repression, jurisdictional reach should also be a key consideration. Title 18 of the US Code already provides jurisdiction outside the United States over a broad range of international crimes such as torture, genocide, war crimes, recruitment of child soldiers, trafficking, piracy, and terrorism.

But jurisdiction must be expansive enough to protect victims. If a bill only allows for the exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction when the perpetrator or victim is a US national (similar to the US war crimes statute), it would fall short. For example, prosecutors would be hindered from bringing a case if foreign family members of a political dissident are being targeted by a foreign state and that political dissident has recently arrived in the United States as a refugee or asylum seeker.

Short of a federal criminal statute specifically addressing transnational repression, other proposals that might help enforce accountability include an extraterritorial federal criminal statute for extrajudicial killings, which could provide accountability if a US-based dissident’s family members are killed. Additionally, Freedom House recommends a “refugee espionage” statute, already in force in some European countries, which would criminalize spying on refugee populations and communities in host countries—a common tactic of transnational repression.

Tools for civil accountability

Meanwhile, laws covering human rights, terrorism, and financial offenses could provide civil remedies for transnational repression.

With respect to Iran, dissidents should be allowed to seek redress when their family members are targeted in their origin countries. Under the “terrorism exception” to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, individuals can sue US-designated state sponsors of terrorism—currently Iran, Syria, North Korea, and Cuba—for extraterritorial acts including torture, extrajudicial killing, and hostage-taking. But that’s only possible if the plaintiffs were US nationals at the time the act occurred.

Congress, however, could amend the statute to allow individuals to sue if they are US nationals or lawful permanent residents at the time the claim is brought, allowing newly arrived dissidents who are the target of transnational repression to hold their governments accountable.

Amending the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act could also lead to broader liability against a foreign government with officials who are sanctioned by the United States for human rights violations by exposing the government to suit for torture or similar violations that constitute transnational repression. Such an amendment is unlikely to provoke concerns from US lawmakers because officials from the countries in question would already be under sanction.

The Homeland and Cyber Threat (HACT) Act, now under consideration in Congress, would partly address transnational repression by allowing dissidents who are US nationals to sue foreign states that mount cyberattacks against them. But it focuses on punishing foreign states for cyberattacks; the private companies who facilitate the sale of the spyware or similar technology should also be held liable.

Successive US Supreme Court judgments have constrained the ability of US-based non-citizen dissidents to sue companies involved in surveillance. These barriers to accountability in domestic law must be removed.

Currently, the legal tools to address transnational repression and hold perpetrators accountable are scattered across various authorities. But the Biden administration and Congress have the opportunity to pull them together in a single package aimed at ensuring criminal and civil liability against individual and state perpetrators. Democratic allies of the United States should also adopt similar measures in a show of unity.

This, in turn, would send a powerful message to the autocrats of the world that targeting dissidents who defend and promote human rights—whether within their borders or without—is never acceptable.

Gissou Nia is a senior fellow with Middle East Programs and head of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project. Follow her on Twitter: @GissouNia.

Further reading

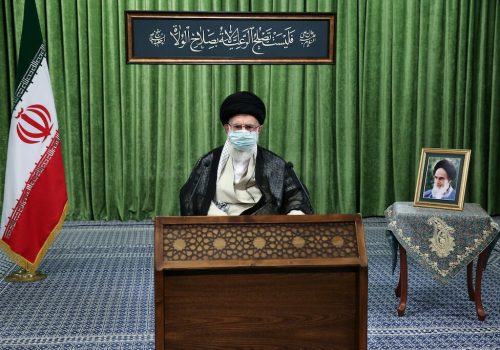

Image: Ruhollah Zam, a dissident journalist who was captured in what Tehran calls an intelligence operation, is seen during his trial in Tehran, Iran June 2, 2020. Picture taken June 2, 2020. Mizan News Agency/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY.