Perhaps it is the fear of Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns” that explains why President Barack Obama has failed to take a more active role in preventing Muammar Gaddafi’s slaughter of his own people. All too often the devil we know, however hideous, is preferable to the devil we don’t know. Obama is treading cautiously in Libya, just as he has in Egypt, Tunisia, and Bahrain, in large part because he cannot be certain that regime change will not be followed by renewed autocracy, Islamic radicalism, or massive civil unrest. Continued temporizing, however, threatens to undermine American interests as well as mock our values. Should Gaddafi and other autocrats prevail, we will be complicit in the defeat of the democracy movements. If the forces of democratic change prevail, newly liberated publics will not forget our tawdry response.

The Obama administration is understandably wary of becoming involved in a third conflict in the Muslim world, a prospect that Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and some senior military leaders reckon will follow any decision to create a no-fly zone in Libya. However altruistic, military involvement could undermine Obama’s efforts to improve America’s image in the Arab world. Coming on the heels of our engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, it could reinforce the view in the Arab street that the US is intent on waging war against Islam. The US could also find itself actively supplying rebel forces with arms and advisors. Worse, if the rebels proved incapable of establishing a cohesive leadership, Libya could become another briar patch from which the US will not easily be able to extricate itself.

At the same time, vacillation could prove damaging to America’s strategic interests over the long term. Choosing to remain on the sidelines while rebels fighting with the equivalent of sticks are trying to topple a dictator is hardly likely to burnish America’s image as a defender of human rights and political self-determination. It may send an unintended signal to other Arab autocrats, as it may already have done in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, that the US will look the other way if they forcefully suppress anti-regime protests. And if the rebels in Benghazi were somehow to prevail, which is looking increasingly dubious, Libyans and others in the Arab world would not soon forget America’s abandonment of them.

To its credit, the Obama administration has frozen the assets of Gaddafi and other Libyan officials and imposed a travel ban. It has also mooted the prospect of creating a no-fly zone and/or finding a way to provide arms to the rebels, but only (and presumably with the Srebrenica tragedy in mind) if Gaddafi’s forces were to intensify their violence against innocent citizens. The president has stated that these measures and continued discussions with the European allies about a no-fly zone are slowly “tightening the noose” on Gaddafi, but they have hardly slowed the eastward advance of government forces, which have retaken Misurata, Brega, and Ajdabiya and are pushing toward Benghazi.

Thus far, Obama has remained impassive (his default position?) to appeals for assistance from the Libyan rebels, a growing chorus of pundits and foreign policy professionals, and even Arab governments. Last week the Gulf Cooperation Council issued a statement that the Gaddafi government was no longer legitimate. Even more remarkably, the Arab League voted on March 12 to accept a UN-backed no-fly zone. If Arab states, all of which in one way or another have tried to suppress the very anti-government protests they are now willing to support in Libya, are prepared to put themselves on the line in the defense of innocent civilians, it is hard to understand how the United States, if not the European allies, can continue to dither.

Obama has wisely responded deliberately to the democracy movements that began in Tunisia and spread throughout the Arab world. It is far from clear that the protests against authoritarian rule will morph into democracies. This is especially true in a country such as Libya, a hodge-podge of tribes that is devoid of institutions. Nor should the United States assume the role of first responder to the crises provoked by public protests in the Middle East and North Africa while European and Arab governments with huge stakes in the outcome remain bystanders.

To continue to dither, however, not only sends a signal to peoples everywhere struggling to assert their dignity and human rights that America does not practice what it preaches, it also undermines US strategic interests, which, our energy dependence aside, stand to be enhanced by the gradual embrace of political pluralism and market economics. For all the disparagement of democracy in the Arab world, there is reason to believe that we are on the verge of a modernizing transformation that, with any luck, will allow societies long suspended in time to reengage the world.

For whatever reason, Obama seems content to defer tough decisions to others, as he did with the healthcare legislation and is doing in the current budget crisis. The president needs to assume the mantle of leadership in responding to the crisis in Libya. In concert with the European allies and the Arab League, the US should come to the aid of the Libyan rebels under the aegis of the United Nations.

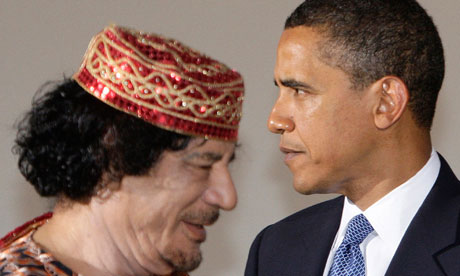

Hugh De Santis is analytic director at Centra Technology. He is a former career officer in the Department of State and chair of the department of national security strategy at the National War College. Photo credit: Alessandro Bianchi/Reuters.

Image: File-photo-of-Obama-and-G-007.jpg