So much attention has gone to Barack Obama’s decision to skip this year’s US-EU Summit — the latest in a now long series of perceived snubs — that almost nobody seems to have noticed what is, at least according to the State Department, a milestone in transatlantic relations.

Just last week in France, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made some fairly monumental statements about the transatlantic relationship. She cast it as nothing less than the “cornerstone of global security and a powerful force for global progress … called to address some of the great challenges in human history,” and Europe itself as the “model for the transformative power of reconciliation, cooperation, and community.”

There was more in her speech than the usual hands across the sea rhetoric about how many times Americans and Frenchmen (and a few other Europeans) have come to each other’s aid during the past two centuries, although there was some of that, too.

If Clinton is to be taken at her word, the transatlantic relationship is about to be reinvigorated like it never has been before, with “a Europe that includes the United States as its partner. And it is a Europe that includes Russia.”

At last, it seems the Obama administration has seen fit to set the record straight about its attitude towards NATO and transatlantic security in general. Europe, evidently, has again become a priority. And it is an awfully big Europe.

Does she really mean it? It’s hard to tell. Most of the speech was aspirational, despite noting that the US and various European governments are now cooperating on everything from Afghanistan and Iran to pandemic disease with half a dozen other issues in between.

But there is much more to be done, particularly in one area she highlighted: energy security. It requires, as she well acknowledged, a credible Russian partner. Yet Clinton, like many people on both sides of the Atlantic, seems to be of two minds.

On the one hand, Russia is to be reminded that the territory and borders must be respected; on the other hand, it is also told, again, that the enlargement of the EU and NATO—groups that exclude Russia but not it former vassals—is a very good thing for everyone.

On the one hand, Russia’s proposals for new European security treaties are applauded for their creativity; on the other hand, Russia is reminded that existing European institutions and arrangements are sufficient and needn’t be duplicated or replaced.

To paraphrase Orwell, some European powers are more European than others.

Ambivalence is contagious, and could be fatal to the transatlantic project if rising expectations continue to disappoint. One hears much of the same rhetoric in Europe about other quasi-European powers like Turkey, or about several smaller states along Europe’s borders that remain suspended somewhere inside the fence, outside it, or interminably on it.

If the past half century of European history has taught us anything, it is of the need to think both big and small at the same time. Many speeches in the 1990s were wasted in talking about “architecture,” and thankfully Clinton spared us that. Instead she spoke positively about institutions and mechanisms, particularly of two councils: the NATO-Russia Council and the new U.S.-EU Energy Council.

Why not integrate the two in a joint EU-NATO-Russia Council for energy security? Its agenda and purview may be limited to the comfort level of the participants, just as the new High Authority of the European Coal and Steel Community began modestly in 1950. But it could finally put a dent in the “zero-sum” thinking that Clinton spoke so strongly against in France.

Barring that, Russia will probably continue to divide Europeans among themselves on this issue, which makes cooperation in other areas difficult; while the US will remain more or less on the sidelines. Lending support to pipeline favorites while preaching in favor of energy diversity is no longer sufficient; a modus vivendi is not likely to emerge on its own, especially in something so vital to suppliers and consumers as energy.

Unity always comes at a price, and one can think of several embedded in a truly all-European energy community. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Clinton has offered a way forward; let’s see if she and her European colleagues can put their money where their mouths are.

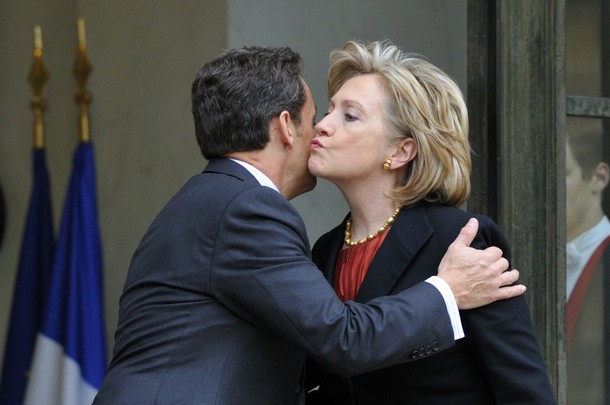

Stephanie Hofmann is an assistant professor at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. Kenneth Weisbrode is a historian at the European University Institute in Florence and the author of The Atlantic Century (Da Capo). Photo credit: Reuters Pictures.

Image: clinton-sarkozy-kiss.jpg