Supporters of the late Venezuelan president, Hugo Chávez, should have a place at the table in a democratic Venezuela, US Special Representative for Venezuela Elliott Abrams said at the Atlantic Council in Washington on April 25.

Nicolás Maduro currently leads the party founded by Chavez—the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). While the United States and more than fifty other countries recognize National Assembly President Juan Guaidó as the interim president of Venezuela, Abrams said PSUV should not be excluded from participating in a future Venezuelan democracy.

“The Maduro regime must come to an end for Venezuela to recover democracy and prosperity,” Abrams said, adding “but like all of the country’s citizens, the PSUV is entitled to a role in rebuilding your country.”

Venezuela has been embroiled in an economic, political, and humanitarian crisis following the collapse of its economy. The inauguration of Maduro to a second presidential term on January 10 following elections widely determined to be fraudulent has only served to sharpen the crisis.

In accordance with the Venezuelan constitution, on January 23, Guaidó took the oath of office as interim president following massive anti-Maduro protests.

The United States has called on Maduro to relinquish power and accede to a political transition leading to free and fair elections. While the United States opposes Maduro and his illegal usurpation of power, Abrams maintained that PSUV is “entitled to run in free elections and try to convince your fellow citizens of the value of your policies.”

Abrams argued that supporters of Chavismo (the political ideology of Chavez) “are watching the Maduro regime destroy [Chavez’s] legacy.” Maduro, Abrams contended, “was selected as president of the PSUV by a very small group of self-interested individuals” who continue to “live like multi-millionaires,” while ordinary Venezuelans live in dire poverty.

Abrams said that “the time to join a free debate about the future is now, and it must include young Chavistas before this regime tries to silence them as well.”

“If you want Chavismo to be part of your country’s future and not just its past, it cannot be imposed by force,” Abrams said in remarks directed at Venezuelans. “When the PSUV accepts that it must act solely as a democratic political party and seek the votes of citizens in free elections solely through argument and debate, Venezuela will be well on the way to democracy.”

Carlos Vecchio, the Venezuelan interim government’s ambassador the United States, agreed with Abrams on the need to include Chavismo supporters in any political transition. “We need to unify our country to have a smooth transition in Venezuela… All Venezuelans are necessary to rebuild our country,” he said.

Gabriela Ramirez, a former ombudswoman for the Venezuelan Supreme Court of Justice and supporter of Chavismo who broke with Maduro’s regime over his disrespect for the constitution, argued that there are many Chavez supporters who think Maduro “is twisting the foundations of Chavismo.”

She stressed that reaching out to this growing number of disaffected Chavistas is crucial as they “can serve as a bridge to some of the popular sectors that supported Chavismo.” Crucially, this outreach will need to explain “that this transition is not about retaliation.”

Ramirez decried the stereotypes of Chavismo supporters, saying that those images were “not helpful.”

“It helps maintain the current regime…[and] is demobilizing an important part of the [group] that will be necessary for change,” she said.

Abrams added that PSUV should not be concerned that the United States or other regional actors would prevent them from taking power if they won legitimate democratic contests. He pointed to the example of El Salvador, where a former leftist rebel leader won free elections in 2009 and 2014. “The United States respected and accepted the outcome,” Abrams explained, adding that Washington actually “continued our foreign aid program there.”

The United States “did not pick El Salvador’s president in those elections and we will not pick who is elected president in Venezuela,” Abrams said.

Another important faction to include in the political transition in Venezuela will be the armed forces, who Jonathan Powell, an associate professor at the University of Central Florida, warned often can be an impediment to successful democratic transfers of power.

“It is very easy after the legacy of repression to look at a military as an enemy of the people or democracy instead of as an important stakeholder,” Powell explained. In order to secure their buy-in, he argued, the transitional government should “truly commit to guaranteeing to the armed forces that they are going to be invested in.”

Abrams conceded that “the country will need to confront the deeds of some who have so badly abused their office or position that there needs to be an accounting. The National Assembly is working on these issues now and with great care.”

As the country moves forward, however, Abrams argued that it “will need a truly professional and well-trained armed forces to rebuild the country and guarantee its security.”

Vecchio added that the interim government is prepared to reach out to the military, as “they are suffering the same things that ordinary people are suffering and we need to talk to them.”

Abrams said the United States “will not waver in its support for freedom in Venezuela, and we are certain we will see again a Venezuela that is democratic, prosperous, and reconnected to the world.” But in order to get there, he argued, “Venezuela needs a peaceful transition negotiated among all its people, between friends and neighbors, in every community. You are all in this together and your politics must reflect that fact.”

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

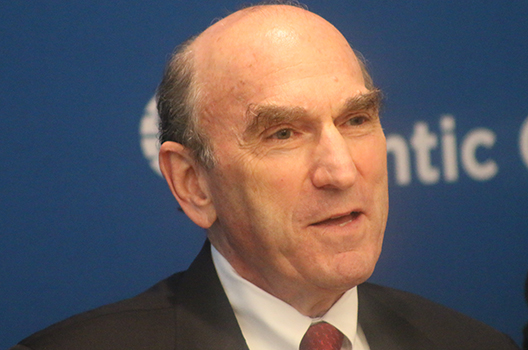

Image: Elliot Abrams, special representative for Venezuela at the US State Department, speaks at the Atlantic Council in Washington, DC on April 25, 2019.