The US airstrikes against Kita’ib Hezbollah (KH) targets in Iraq and Syria on December 29 were an appropriate response to ongoing provocation by Iran and its proxies. In addition to multiple attacks against US bases in Iraq, the latest of which killed a contractor and wounded several other personnel, Iranian proxies attacked the US Embassy in Baghdad in May, September, and October. In the October attack they killed an Iraqi soldier. Moreover, Iranian proxy attacks are not limited to US military targets. In addition to their well-known role in murdering, extorting, and displacing Iraqis of all sects who stood in their way, Iranian proxies more recently deployed snipers to fire at protestors in Baghdad and sent their members into Tahrir square where they stabbed a number of other protestors who had gathered there.

It is a very bad idea to turn Iraq into a battlefield (again). However, it is a worse idea to let Tehran use certain militias to continue to derail Iraq’s recovery, reconciliation, and reconstruction. Iran’s destabilizing influence has sparked the current protests; moreover, the ongoing security threat Iranian proxies pose has limited foreign investment and economic growth, which in turn impedes the only path for the Iraqi government to meet protestor demands. It is certainly the case that the United States will have to accept a role for Iran in Iraq; however, the Iranians will likewise have to accept a role for the United States. If they do not, then the fault for turning Iraq into a battlefield lies with them.

The Iraqi government response was disappointing but predictable. Both outgoing Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi and President Barham Saleh not only condemned the attacks but reportedly tried to get them called off. While it is tempting to dismiss their responses as further evidence of Tehran’s influence, the cross-sectarian consensus is a clear indicator that more than just Iran’s interests are in play here. Getting into the middle of the ongoing US-Iran feud does not play well in Iraqi politics and risks generating the same negative response the population has directed at Iran.

Having said that, the United States was right to send a message that it will defend itself. If hit, it makes sense to hit back harder. However, it is important to understand the kind of conflict we are in. There is no scenario where there will be a decisive battle or where overwhelming force will win the day. KH will adapt by moving military assets closer to civilians. Tehran’s supporters in Baghdad will increase political pressure to get the government and parliament to limit, if not cease, security cooperation with the United States and order the withdrawal of US forces. Baghdad has already threatened to review its relationship with Washington. It will be a test of the US-Iraq relationship to see how the new Iraqi government will ultimately respond.

The way forward: Managing the escalation

The key to prevailing in such conflicts is not simply the ability to escalate but the ability to manage that escalation. Iran and its proxies will retaliate and very likely against a relatively undefended target, possibly outside Iraq. They have already attacked the US Embassy in Baghdad, but they are unlikely to stop there. For example, in 1983 an Iranian proxy attacked the US embassy in Kuwait because of US support for Saddam Hussein. There is no reason to suppose they will not do something similar again outside of Iraq and Syria. The United States needs to have options in place for when, not if, that attack comes.

Effective escalation management requires at least three things: 1) a demonstrated willingness and capability to strike; 2) an “off-ramp” that gives an adversary a less costly but acceptable option other than continued escalation; and 3) a consensus among key allies and partners regarding the legitimacy of one’s response.

Willingness and capability

The strikes on December 29 went a long way to demonstrate willingness. But, as discussed above, the backlash from Iraqis may limit US capability to conduct future operations. For that reason, the United States should reverse any plans for a withdrawal from Syria and instead establish bases from which it can conduct future operations. Not only will such bases provide greater flexibility, but they will also signal to the Iranians that further retaliation means more US military in the region and not less. It goes without saying that the United States should begin, if it has not already done so, to negotiate permissions from other regional partners for using their territory for strikes against Iran, should Iran retaliate.

Off-Ramp

A good off-ramp is a clear policy statement that gives the adversary something it can do that will avoid further retaliation. “Can do” here simply means an alternative that represents a lower cost than continued escalation. By using proxies, the Iranians have something of an advantage. KH bore the brunt of the costs and it will be interesting to see if they are willing to continue to expose themselves to future retaliation. This point suggests off-ramps will apply to militias differently than they will with Iran and the United States should take that difference into consideration.

In conflicts like this, carrots are as important as sticks. So, it is in the US interest to consider options that incentivize cooperation as well as ones that dis-incentivize aggression. It is beyond the scope of this piece to determine the range of possible incentives. However, for the militias, dropping US opposition to their status as a separate Iraqi security force—as opposed to integrating fully under the Iraqi armed forces—may be worthwhile if it gets them to stop attacks on US forces. For the Iranians, confidence building measures that US forces in Iraq will not be used against Iranian targets may also be worthwhile, even if the likelihood of escalation elsewhere exists.

Consensus

The perception that a US response is illegitimate, or even just ill-considered, opens up opportunities for the Iranians to drive a wedge between the United States and its allies, partners, or other stakeholders in the Middle East and Europe that could render US efforts incoherent. If partners act to limit our options or, more importantly, increase Iran’s or make it more resilient, the US response will have been for nothing. Russia, for example has condemned the US attacks. If it were to support Tehran the way it has Damascus, Iran’s hand would be significantly strengthened.

Maintaining support among the Iraqis will be especially tricky. The United States needs to be clear, however, about what it wants the Iraqis to do. Any way ahead should not be about getting the Iraqis to pick the United States over Iran in the broader conflict. Rather, the United States should focus on getting Iraq to fulfill its obligations regarding the security of US personnel operating in their country. To incentivize that decision, using means other than humanitarian aid, the United States should tie as much of its economic and other assistance to continued military cooperation. If the Iraqis continue to allow Iran and its proxies to threaten US personnel, they need to know that will come at a cost that the Iranians cannot replace.

In this regard, it may also make sense to consider taking the Iraqi Kurds up on their offer to station US forces permanently in Iraqi Kurdistan. Baghdad will not be happy about that. The tension between Baghdad and Erbil has always been difficult for the United States to navigate. Conventional wisdom has been not to alienate Baghdad when supporting Kurdish interests. Doing so would push Baghdad closer to Tehran who opposed any move that enabled greater Kurdish autonomy, much less independence. Should Baghdad side with Iran, however, that concern would be resolved. Of course, should the United States decide to station troops in the Kurdish territory, it will have to consider access issues as Baghdad will undoubtedly close its airspace and borders as it did after the Kurdish independence referendum in 2017.

If Iraq wants to become as isolated and poor as its Iranian neighbor, there is little the United States can do to prevent it. More to the point, the United States should make it clear to Iraqi political leaders that is the path they are on should they side with Iran. But in retaliating against Iranian provocation, the United States needs to provide Iraqis with alternatives they can choose. Few Iraqi leaders—of any political or sectarian affiliation—can sanction a conflict with Iran. Therefore, the United States needs to be clear that while it will defend its troops and other interests, Iraq can choose to control the militias and limit cooperation with Iran in order to prevent turning Iraq into a battlefield yet again, which would certainly not be in Iraq’s interest.

Dr. C. Anthony Pfaff is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative and research professor for Strategy, the Military Profession, and Ethic at the US Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute. The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily the United States Government.

Further reading:

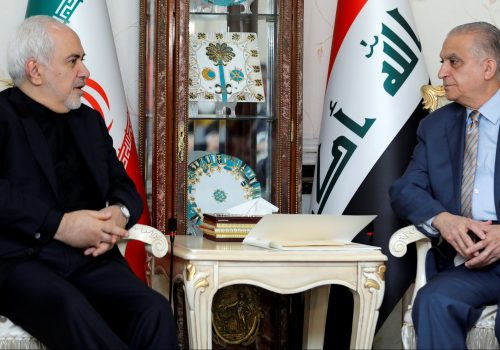

Image: Hashd al-Shaabi (paramilitary forces) fighters carry coffins of members of Kataib Hezbollah militia group, who were killed by U.S. air strikes in Qaim district, during a funeral in the holy city of Najaf, Iraq December 31, 2019. REUTERS/Alaa al-Marjani