Tuesday, May 1 may mark the start of a fully fledged global trade dispute.

Tuesday, May 1 may mark the start of a fully fledged global trade dispute.

US President Donald J. Trump announced tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum products into the United States on March 23, granting temporary exemptions for only seven key US allies of the US: the European Union (EU), Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Canada, Mexico, and South Korea. Those exemptions expire on May 1.

The day before announcing the tariffs, Trump hinted at the conditions for the permanent exemption of countries, namely to “arrive at a satisfactory alternative means to address the threat to the national security.” What this means on a country-by-country basis remains unclear, but many have tried to extend their exemptions from Trump’s tariffs.

So far, only South Korea has successfully negotiated a permanent exemption from tariffs in the framework of the Korus agreement, capping its annual exports to the United States at 70 percent of the average of steel and aluminum exports between 2015 and 2017.

But what about the others?

Canada and Mexico are currently engaged in renegotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States. Last week, negotiators claimed that a deal is “reasonably close”. While the tariffs on steel and aluminum are not part of the official negotiations, sufficient advances in the talks might result in an extension and potentially a permanent exemption for Canada and Mexico, as was the case for South Korea.

From April 13-14, Brazil engaged in bilateral talks with the United States in the context of the Summit of the Americas in Peru. US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross reportedly suggested the possibility of a permanent exemption if Brazil were to agree on a quota on its exports of steel and aluminum products to the United States. That solution was not acceptable to Brazil. By contrast, the Argentine government is negotiating a voluntary quota on its steel and aluminum exports to the United States.

While these Latin American nations have begun key discussions and continue to move toward an agreement, Australia’s representatives have still not reached a concrete decision with their counterparts in the United States. Australian Minister for Trade Steven Ciobo visited Washington just last week, but his talks with the US administration did not produce any official decision on the status of Australia’s exemption.

French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are the most recent European leaders to travel to Washington to make the case on behalf of the EU’s twenty-eight member states for a permanent exemption. During a speech before a joint session of the US Congress on April 25, Macron strongly condemned the looming tariffs, stating that “a commercial war opposing allies is not consistent our mission, with our history, with our current commitments to global security.” Neither Macron nor Merkel returned to Europe with a positive message.

Despite European Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström’s belief that the EU would win the potential dispute at the World Trade Organization (WTO), conflict resolution at the WTO is a lengthy process. It requires time that the EU, the United States, and the world economy do not have. Because of these circumstances, the EU has asked for permanent exemption with no strings attached. “We have not offered the US anything, we are not going to offer them anything to get exemptions from tariffs that we consider are not in compliance with the WTO,” Malmström said.

Accordingly, the EU, on April 16, filed an official complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) reasoning that, “notwithstanding the United States’ characterization of these measures as security measures, they are in essence safeguard measures.” Instead, Malmström suggested closer cooperation between the Brussels and Washington to find a solution to the overcapacity of steel and aluminum. The two sides have recently started an official dialogue on the issue.

In stark contrast, Larry Kudlow, director of the National Economic Council, said the United States expects “that some of our friends make some concessions with respect to trading practices, tariffs and taxes.” He mentioned a change in the tariffs on US car imports into the EU as a concrete example: “One of the issues cropping up is the equal treatment of automobiles. We’d like to see some concessions from Europe.”

What happens next?

On April 28, Ross mentioned the possibility of an extension of the May 1 deadline for some countries, but did not disclose specifics. Any deals to be struck ahead of the exemption expiration are likely to be on the basis of self-imposed export quotas to the United States.

In the case of the European Union, the trading bloc of twenty-eight countries aim to be permanently exempt from the tariffs, with the understanding that the United States and Europe would start negotiating a new trade deal. This new deal would aim to eliminate tariffs in such a way as would benefit both sides, as well as address the Trump administration’s concerns regarding its trade deficit with Europe. A deal of this kind would take time—the European Commission will have to negotiate on behalf of its member states while taking into account each of the countries’ national circumstances.

The option of a transatlantic trade deal was also mentioned last week by Merkel. During a press conference with Trump, she said that a bilateral trade deal seems to be a good solution, as the WTO has been unable to deliver multilateral agreements for some time.

With similarly harsh words directed toward the WTO, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said: “We are ready to open a discussion with our American friends on the future of the WTO, on the improvement of the WTO, and the whole multilateral trade system.” However, in line with his European counterparts, he also made clear that, “first of all we have to get rid of that question of new tariffs.”

Another concrete option would be for the EU to raise an import quota on US beef, which would be an overhaul of a 2009 agreement. In light of the Trump administration’s focus on agriculture, this might be a good strategic move, yet presumably insufficient to put a permanent halt to the tariffs. While the European Commission has recently closed a public consultation that looked into raising the quota of US beef coming into the EU, it claims the timing is unrelated to the looming May 1 deadline.

In the worst-case scenario, tariffs will come into effect for all countries but South Korea. In most cases, the affected countries will retaliate within the framework of the WTO. The European Union has been vocal about its contingency plan, and already released a list of potential retaliatory US target products worth roughly $3.4 billion in March. The ten-page list reads like a shopping list of American stereotypes, including orange juice, peanut butter, Harley Davidson motorbikes, cranberries, bourbon, and tobacco.

While planning retaliation, the EU is looking into precautionary measures and safeguards to protect their markets from being flooded by countries who originally exported to the United States, but now need to trade elsewhere. Other countries affected by the tariffs will likely take similar steps, making markets overall less open and more protectionist. In addition, the United States’ current blackmail diplomacy on its closest allies might render them less willing to side with Washington in its trade dispute with China.

Despite the high economic and political stakes, all that remains is to wait and see what May 1 will bring. As Merkel said: “The decision lies with the president.”

Marie Kasperek is associate director of the Global Business and Economics Program at the Atlantic Council. You can follow her on Twitter @MarieKasperek.

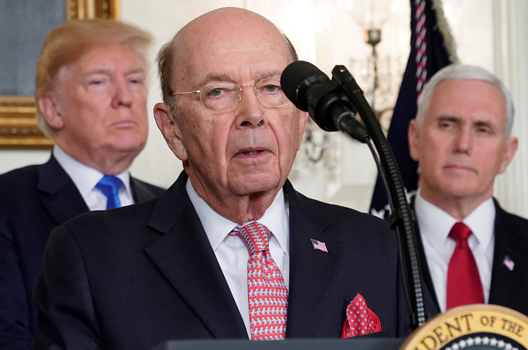

Image: US President Donald Trump, flanked by Vice President Mike Pence, listens to remarks by Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross discuss tariffs at the White House in Washington, U.S. March 22, 2018. (REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst)