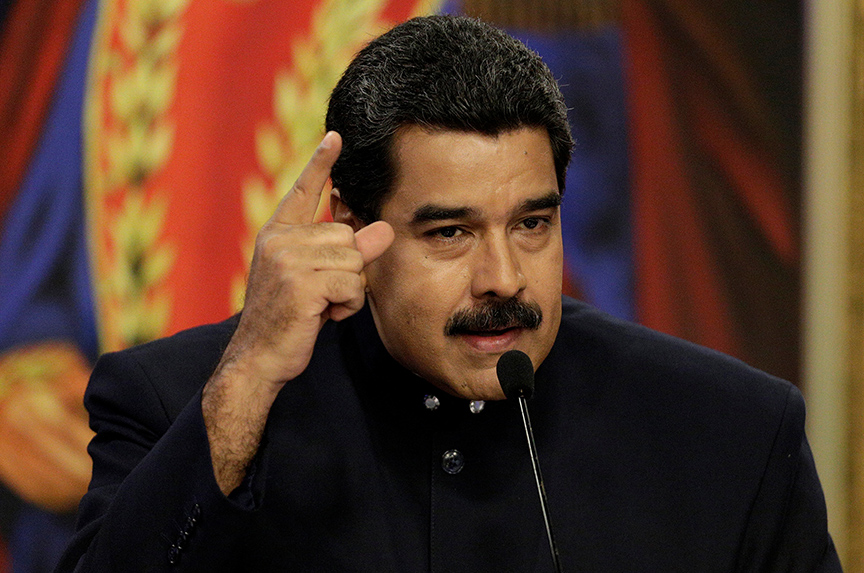

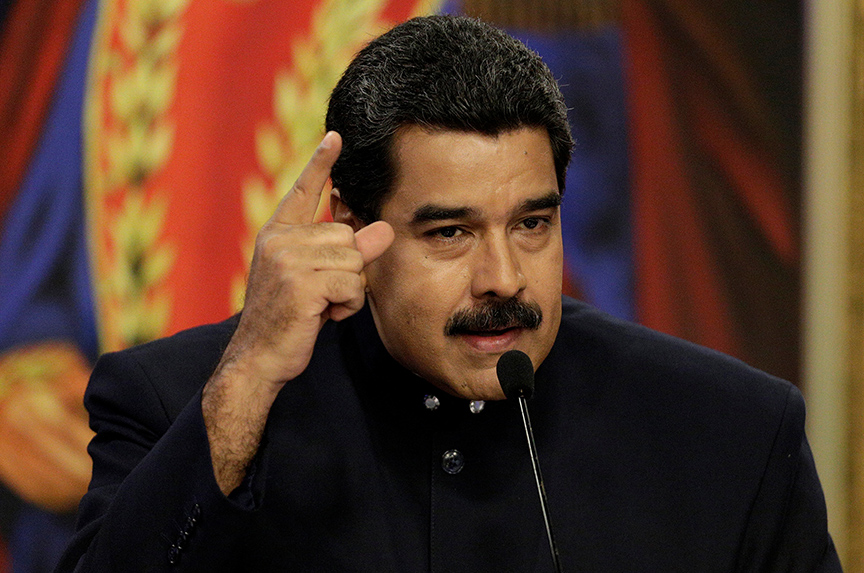

Nicolás Maduro is expected to be re-elected president of Venezuela on May 20 in an election that most experts agree is a sham the United States and several Latin American countries have refused to recognize, and the European Union wants suspended until the conditions are suitable to organize a free and fair vote.

Nicolás Maduro is expected to be re-elected president of Venezuela on May 20 in an election that most experts agree is a sham the United States and several Latin American countries have refused to recognize, and the European Union wants suspended until the conditions are suitable to organize a free and fair vote.

“Rather than an election, it is really an electoral event because we know who the winner will be on May 20,” said Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

“All the conditions leading up to the electoral event—including the barring of opposition candidates, the lack of international observation, the government control of the electoral council, the scare tactics imposed on the people—means that whatever the outcome is it will be the one chosen by the Maduro regime,” he added.

On May 14, the Lima Group, comprised largely of Latin American nations and set up to address the crisis in Venezuela, urged the Maduro government to suspend the election calling the process “illegitimate and lacking in credibility.”

The main opposition to Maduro—a coalition of political parties known as the Democratic Unity Roundtable—has said it will boycott the election. The most popular opposition leaders—including Leopoldo López and Henrique Capriles—are in prison, in exile, or banned by the government from running for office.

Of the candidates who are allowed to compete against Maduro, Henri Falcón is considered the strongest. He has even led Maduro in some polls. Falcón, a former Chavista—one who subscribes to the regime’s leftist ideology, is the head of the anti-Chavista party Progressive Advance. Javier Bertucci, an evangelical pastor, and Reinaldo Quijada of the Unidad Politica Popular 89 are the other two notable presidential candidates.

The election takes place at a time when Venezuela is in the midst of a humanitarian and economic disaster. Maduro has blamed the dismal conditions in his country on US, European Union, and Canadian sanctions.

Speaking at the Atlantic Council on April 30, Michael Fitzpatrick, deputy assistant secretary in the State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, called this a “false argument.”

The United States would consider lifting sanctions on Venezuelan officials provided they take steps to ease the political, humanitarian, and economic crisis that is gripping their country, Fitzpatrick said.

Pointing out that most of the US sanctions are on individual members of the Venezuelan regime, Fitzpatrick added: “What we are trying to do is to ensure that… we are not complicit in the wholesale looting of the financial coffers of Venezuela.”

A national door-to-door poll conducted by the Atlantic Council in Venezuela in March found that more than eight in ten Venezuelans believe that the country is mired in a humanitarian crisis, more than nine in ten Venezuelans consider food and medicine supply to be insufficient. Chavistas were among those polled.

Food and medicine are in short supply. Previously controlled diseases, such as malaria, are breaking out in the most populous areas at levels not seen in the past seventy-five years.

This dire situation has produced a migrant crisis that has strained Venezuela’s neighbors. In the past few years, more than 1.5 million Venezuelans have fled Venezuela, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

“If the government cannot provide basic food, medicine, and conditions for daily survival that is what in the end will threaten [Maduro’s] ability to hold on to power,” said Marczak.

Jason Marczak spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: Is there a risk that this election in Venezuela, rather than bringing about regime change, will further consolidate Maduro’s hold on power?

Marczak: Rather than an election, it is really an electoral event because we know who the winner will be on May 20. All the conditions leading up to the electoral event—including the barring of opposition candidates, the lack of international observation, the government control of the electoral council, the scare tactics imposed on the people—means that whatever the outcome is it will be the one chosen by the Maduro regime.

The power is held right now by Maduro and a group of close advisors who have no intention of relinquishing that power. Their hold on power grows as people leave the country. The migrants and refugees are largely those who do not support the government and thus have little access to the basic goods necessary for daily survival. But Maduro’s hold potentially could become more tenuous as the humanitarian situation deteriorates and as hyperinflation continues to grip the country. Venezuela will increasingly plunge to depths that would be unimaginable in this hemisphere.

Q: What would a consolidation of Maduro’s power mean for Venezuela?

Marczak: There is some speculation that Maduro will use the electoral event on May 20 to push for a referendum to approve a new constitution. And that new constitution could eliminate any of the last remaining mechanisms for dissent, including putting in place new laws that would squash the opposition. In the midst of this growing humanitarian and economic crisis, Maduro is likely to resort to all-out total control to attempt to suppress the population. But if the government cannot provide basic food, medicine, and conditions for daily survival that is what in the end will threaten his ability to hold on to power.

Q: Some opposition figures have said that by taking part in the election candidates like Henri Falcón are legitimizing the process. Do you agree?

Marczak: There are upwards of fifty countries that have said they don’t consider the results of the election to be legitimate. There is no credible international monitoring of this election. In the eyes of many Venezuelans and in the eyes of the international community Henri Falcón represents his own interests. He is not representative of the many opposition parties that have come together to denounce the electoral process.

Q: Why has the opposition not been able to form a united coalition?

Marczak: The opposition recently did form the Frente Amplio, which brings together opposition parties, NGOs, unions, and civil society in a broad front united to defend the interests of the people.

In the past, the opposition parties have struggled to coalesce around one common vision.

Each party, each leader have their own interests as top of the agenda. But I see the depths of the crisis and a renewed commitment among some, but not all, political leaders in the country as a step forward. Still more work needs to be done.

Another challenge is that many members of the political opposition have not only been barred from running for office but have been forced to leave the country. And those who remain must live in constant fear of being arrested and put in jail as a political prisoner. This makes communication and organization incredibly challenging.

Q: In the international community is there a unified position on how to address the crisis in Venezuela?

Marczak: There are a number of different countries that have been working together—whether it is the Lima Group of Latin American countries or the United States and its partners, including the European Union.

Especially around the May 20 vote, there is a unified position that this election is neither free nor fair, that it is illegitimate, and that the results will only speak to the fraudulent process. What is key in Venezuela is to address the situation from a multilateral perspective. The United States has been seeking to do that. It has been working with a number of countries across the region and more broadly to try to put forward a common position and to try to coordinate efforts. In the end, what’s most important, whether we’re talking about sanctions or any other effort, is not that that effort is just advanced by one particular country but that there is a broad coalition that is working together. It is broad coalition that is going to result in some type of impact.

Q: How specifically should the United States address this crisis?

Marczak: The United States should address the crisis by continuing to ramp up pressure on the Maduro regime. The series of individual sanctions that we have seen ratchet up over the course of the past year have put additional pressure on members of the Venezuelan political elite. Those sanctions have been imposed because those people have violated basic international norms or laws, whether it is corruption, money laundering, indiscriminate violations of basic human rights. The individual and financial sanctions have put additional pressure on government officials. That pressure is critical moving forward, but at the same time what’s critical is to provide mechanisms to relieve the humanitarian pressure. That is a real challenge because first Maduro would have to accept international assistance and then the question becomes how do you provide that assistance in a way that improves the daily lives of Venezuelans but doesn’t give a new lease on life to the Maduro regime.

Q: How should the Lima Group address this crisis?

Marczak: For the Lima Group and Latin American countries specifically, international diplomatic pressure is critical as is support for the opposition in Venezuela. [The late Venezuelan President Hugo] Chavez and now Maduro have gone to great lengths to try to rally international legitimacy for their efforts in Venezuela. There was the creation of Petrocaribe and efforts at the Organization of American States to buy votes from smaller countries. That international legitimacy is still craved by the Maduro regime and that is a pressure point for the Lima Group.

Q: What role is Cuba playing in supporting the Maduro regime?

Marczak: Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez had a very close relationship. The Cuban intelligence is very much intertwined with the Venezuelan state. Cuba has become quite dependent upon Venezuela’s petroleum exports, both for satisfying its own internal energy needs but also for selling Venezuelan crude on the international market for hard currency. Just this week it was revealed that Venezuela had purchased nearly $500 million in Russian oil for Cuba.

Q: What can China do to resolve crisis in Venezuela?

Marczak: China could potentially be part of the solution. The Chinese are owed a lot of money. Chinese loans to Venezuela are in the tens of billions. Venezuela in exchange has to provide China with crude exports. The Chinese are concerned that the Venezuelans will not be able to continue with their payments. It is not in the immediate term, but a medium-term solution could allow for the Chinese to potentially play some type of constructive role. Of course, the Chinese will not want to get involved in any political discussion in Venezuela. Their involvement would be limited to ensuring the repayment of loans and broader economic issues.

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

Jason Marczak is director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. Follow him on Twitter @jmarczak.

Image: Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro addressed journalists at Miraflores Palace in Caracas, Venezuela, on August 22. Maduro’s attempts to monopolize power and his crack down on opposition protesters have precipitated a crisis in Venezuela. The United States can best address this crisis through “a carrot-and-stick approach, working collaboratively with friends and allies across the hemisphere,” said Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. (Reuters/Marco Bello)