Even by Venezuela’s standards, it has been an unprecedented week for this oil-rich South American nation. In a span of a few days, the crisis that has been simmering for the past few years has reached a boiling point as the international community, including the United States, has turned up the heat on Nicolás Maduro’s regime.

Here’s a quick recap:

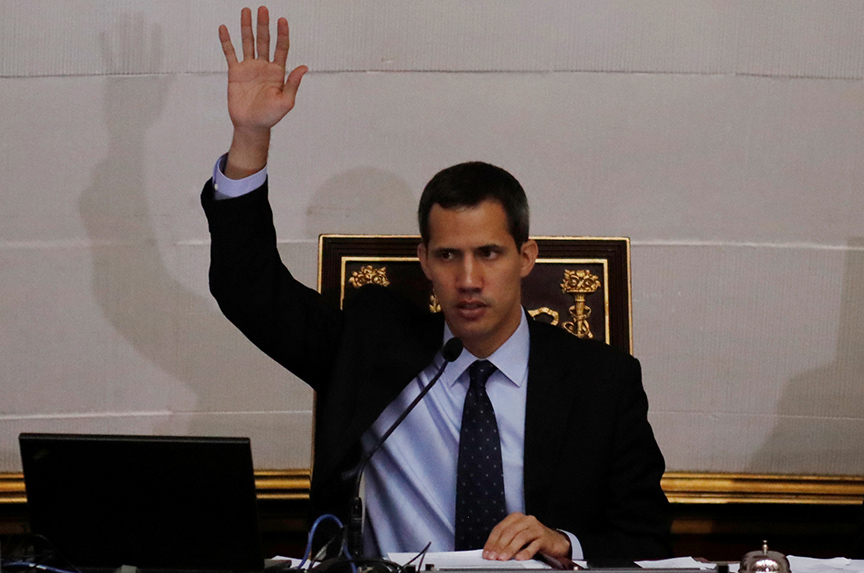

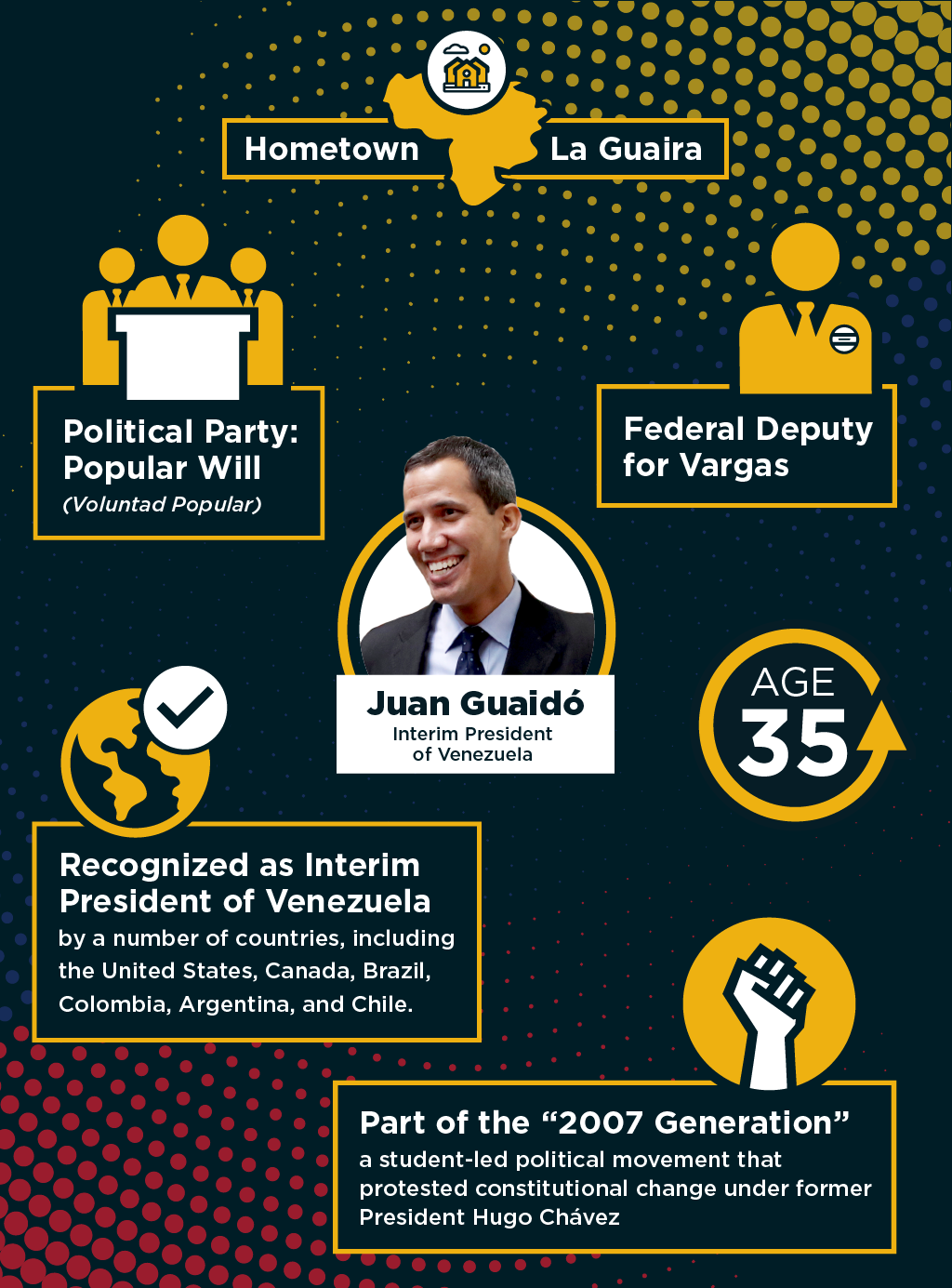

- January 23: National Assembly President Juan Guaidó took the oath of office as interim president following Maduro’s assumption of a second term two weeks earlier based on fraudulent election results—a view shared by scores of countries around the world. [Article 233 of the Venezuelan Constitution states that the president of the National Assembly has the ability to serve as interim president and to call elections when the office of the president becomes vacant.] In an interview with the BBC, Guaidó defended his claim to be interim president and said: “My duty is to call for free elections because there is an abuse of power and we live in a dictatorship.”

- The United States joined about twenty other countries in recognizing Guaidó as the interim president of Venezuela. Russia, China, and Turkey are among the countries that continue to support Maduro.

- Maduro cuts off diplomatic relations with the United States and gives US diplomats seventy-two hours to leave Venezuela. [Maduro later did an about face on his expulsion decision.]

- January 28: The Trump administration announced sanctions on PDVSA, Venezuela’s state-owned oil company—an act that will likely choke off a vital source of revenue for Maduro.

- US National Security Advisor John Bolton does not rule out military intervention. “The president has made it clear that all options are on the table,” Bolton told reporters in the White House briefing room.

- January 29: The Maduro regime on January 29 barred Guaidó from leaving the country and ordered that his assets be frozen.

Venezuela is in the grips of a crisis that has been marked by hyperinflation, shortages of food and medicine, and political repression. Millions of Venezuelans have fled the country. Meanwhile, as anti-Maduro protests have gained momentum, the United Nations estimates at least forty people have died in the unrest.

Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, discussed the latest developments in Venezuela in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts of our interview.

Q: What are the implications of the sanctions that the Trump administration has placed on PDVSA?

Marczak: The sanctions are an important step toward giving interim President Guaidó the necessary financial tools for the interim government. The sanctions are not a ban on oil imports. Rather, they restrict Maduro and his loyalists from accessing any revenue from oil sales.

The sanctions have implications in the United States, but they also have extraterritorial implications given that they prohibit access to PDVSA’s dealings with the US financial system at large. It’s important to note that some of the effects of the sanctions will be phased in. There are a number of different policy changes mentioned in the executive order that will not come into effect until the spring or the summer.

The broader effect of the sanctions is to tighten the noose around Maduro, to deny him access to critical resources and access to the money that is used to pay off those who have been loyal to him thus far. It will become increasingly difficult for Maduro to buy support from those critical to him maintaining power without access to the PDVSA funds.

Q: Is the military then likely to peel away from Maduro?

Marczak: The money from PDVSA that is used for illicit purposes is not going to the rank and file of the military, it is going to the top brass. The sanctions may have an impact on the loyalty of those in the upper echelons of the military. Separate from the sanctions though, I think the actions taken by Juan Guaidó’s interim government, the statement by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo offering Venezuela $20 million in humanitarian relief, are all messages to the rank and file of the Venezuelan military that there is a brighter future and if they want to be on the right side of history they need to be part of the transition that is going on.

The development over the weekend of an amnesty [offered by Guaidó] is yet another tool to show those whose power is so critical for the interim government that abandoning Maduro is their best option because it gives them a future that doesn’t necessarily result in retribution.

Q: What are Venezuela’s main sources of revenue?

Marczak: Over 95 percent of the hard currency that comes into Venezuela is from oil. It’s a critical source of revenue even though Venezuela’s oil output has declined significantly in the past few years. Over forty percent of Venezuelan oil goes to the United States. Still, its petroleum exports to the United States took a nosedive from 2016 and 2017—from 24 million barrels per month to about 16 million barrels per month.

Venezuela has also started to sell gold to Turkey. There were upwards of $1 billion in gold sales to Turkey in 2018.

This is an economy that is in the doldrums, but the one source of funding that does come in is through the oil sector. But that money doesn’t reach the Venezuelan people who are suffering. Over the last twenty years, Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro have systematically stamped out private sector investment in the country.

Q: What is the likelihood that the Trump administration will impose an oil embargo?

Marczak: I don’t think we’re there right now. The executive order [on January 28] will de facto scale back Venezuelan oil exports to the United States since Maduro knows he can no longer access the revenue from those exports. At the current moment, I don’t see oil sanctions as being more helpful than what has already been done to try to achieve the policy goal: to support the interim government.

Q: Venezuela has been a top supplier of crude oil to the United States. What would be the implications of an oil embargo for the United States?

Marczak: Venezuela is a top supplier of crude, but at the same time Venezuelan oil exports to the United States have declined precipitously in the last couple of years. Venezuela still makes up about 7 percent of US petroleum imports. There would be an effect on the US energy market, but probably not the same effect that we would have seen five years ago—one, because of the decrease in oil exports and two, because of the fact that for quite some time there has been a possibility of a full curtailment of Venezuelan oil imports. There has been some effort to mitigate the impact of that.

Q: Can Guaidó call elections?

Marczak: Yes. Under the Venezuelan Constitution, when the office of the president is vacant, which it is given the illegitimacy of the vote last spring, the National Assembly president takes office and has forty-five days to call elections. These elections would have to be free and fair. There are a number of different conditions for what constitutes a free and fair election. A recent Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center infographic details the basic international norms critical for free and fair elections and shows that last May’s election didn’t meet any of those demands.

Q: What developments should we watch for in the days to come?

Marczak: The EU foreign ministers are meeting on January 31. And this weekend is the end of the deadline that EU members put for Maduro to announce free elections. There will be a whole other set of rallies over the weekend. I would expect more countries to recognize the interim government and more action taken by those who do recognize the interim government to tighten the screws on Maduro. But pay a close eye to the spoiler role that Russia may increasingly try to take.

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

Image: Juan Guaidó, recognized by the United States as the interim president of Venezuela, attended a session of Venezuela's National Assembly in Caracas on January 29. (Reuters/Carlos Garcia Rawlins)