The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has brought the state roaring back. As the virus has spread around the world, state control over all aspects of life is now well accepted—just as in a wartime economy—except this time the enemy is an invisible, silent killer disease. The state was omnipresent in China—where the virus originated—and its role in society and the economy was well accepted. But now all over the world, even in countries where the role of the government was not so big, governments are stepping into almost all aspects of life in ways that could not be imagined a few months ago.

Despite its worldwide spread, global cooperation is strikingly absent this time. China and the United States continue to compete for global leadership—a trade war between them is on hold for now. The UK has just exited from the EU and solidarity within the EU is being tested. Russia and Saudi Arabia unleashed an oil price war. Global forums such as the Group of Twenty (G20) which should be at the forefront of a coordinated global response to the pandemic are helpless. A virtual G20 meeting, promised $5 trillion to help—but this figure was just the cumulative total of what each government is planning to do internally. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have promised large sums of money—but these will have to be borrowed. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been found wanting in even recognizing the dangers.

Countries with smarter and more effective government, such as Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, New Zealand, and Germany have managed to respond better to the crisis. Even the Indian state of Kerala, despite large numbers of returning migrants, has responded comprehensively and quickly. Governments that have been slower to respond like Italy, Spain, the UK, and the United States are struggling, despite having considerable institutional capacity and well-developed health systems. But given their vast resources, they will eventually come through—albeit at higher costs to their people and economies. In the developing world where government capabilities are much weaker and health systems are underfunded, the potential spread of the virus spread could make them unable to cope without massive international assistance. The world must remember that unless the virus is brought under control everywhere it risks coming back anywhere. But what is clear is that the state is back in three significant ways.

First, invoking war powers to ensure the saving of lives. Just as in previous crises, the world was unprepared for the coronavirus. The World Economic Forum’s 2020 Risks Report mentioned a disease pandemic, but not within the top ten. Five year ago, Bill Gates said that “the world needs to prepare for pandemics in the same serious way as it prepares for war”—but was not taken seriously. There were warnings—with the swine flu in 2009 and Ebola in 2014-16—but these were forgotten when those viruses subsided. A 2011 Hollywood movie “Contagion” was amazingly prescient in showing the havoc a pandemic can cause—but the attention it brought soon faded away.

The Global Health Security Index produced in October 2019 by the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Johns Hopkins Global Health Center—just a few weeks before the onset of the coronavirus—showed that no country was adequately prepared to deal with pandemics. The world was increasing defense expenditures but reducing health spending. Military spending was higher than public health expenditure in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, North Africa, and Central and South Asia. The need now is for more weapons to fight a virus—not more weapons to kill each other—but the world is clearly under-prepared. But now with a full-blown pandemic, the state is back in a war-like mode against a silent killer—invoking war powers to provide health care and life support. US President Donald J. Trump has already declared himself a “war-time” president and invoked war production powers to combat the COVID-19 crisis.

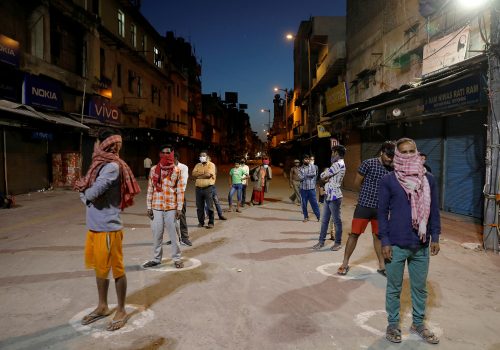

Second, the global economy is on life support, once again requiring government assistance—even more so than with the global financial crisis. That emergency required the state to step in, but fiscal policy played a somewhat secondary role to monetary policy. The central banks played a prominent role with quantitative easing programs used aggressively—some say too aggressively—to help sustain a recovery which has lasted more than a decade. This time monetary policy seems less useful—as the problem is not lack of liquidity—but a seizure of economic activity and breakdown of supply chains. Fiscal and industrial policy now needed to provide unemployment benefits, ensure vital goods are available, and to provide economic support and even payroll supplements to affected businesses. A massive $2 trillion (10 percent of gross domestic product) life and economic support package has just been assembled, which puts the federal government into every aspect of economic activity. In the EU, governments are providing payroll support to businesses and the central bank is buying corporate paper. Complete lockdowns in India, Italy, Spain, and the UK on a scale unimaginable even in wartime have been introduced.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, global trade had begun to plateau and global trade wars had brought the state back in regulating trade and increasing protectionism to save local jobs and industry. But even then, global and regional value chains were still seen as the most efficient way to maximize global economic growth. But with COVID-19 running havoc, the idea of ensuring strategic industries have more local sourcing has re-emerged just as it did in war-time situations. The state’s role in ensuring vital production will now be back in any post COVID-19 world and globalization will retreat further. The just-in-time global value chain has been shown in this crisis to carry huge risks and large costs when these chains are disrupted. Global businesses will inevitably rethink how to build more resilience in their business models—especially in vital industries like pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, food, and other vital sectors.

Third, the role of the state in society will change our concepts of privacy and rights—especially as the state mobilizes and regulates society to fight the virus. China’s use of surveillance technology, tracking people’s movements, and even civic scorecards were seen by much of the democratic world as the aberrations of a totalitarian state. With COVID-19 response now requiring similar approaches in democracies to maintain social distancing, the aversion to big brother Orwellian state is now weakening. As states look to combat fake news, they may become more accepting of the need to regulate “free” speech with a much bigger role for state agencies in policing content. Will states be able to maintain the right balance between draconian state powers to fight the pandemic and the perseverance of individual freedoms?

Perhaps some things will return to the way they were before the pandemic, but the role of the state and its relation to the economy and society will not be the same after this. Globalization, which was already under attack from trade wars, will most likely retreat further and national and local resilience will be more prominent in the way societies and businesses function. Global business models will be forced to build more resilience into their supply chains, with less focus on looking for the cheapest global sourcing, as the costs of potential disruptions have been shown to be too high. Governments will require more local and national sourcing for vital and strategic sectors like food, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment. And much greater surveillance will become more acceptable in many parts of the world.

One big lesson is that our biggest risks going forward are collective—not against each other. We have to prepare ourselves to fight the right wars—pandemics, climate change, rising natural disasters—and build state capacity and more resilient economies and global institutions to effectively deal with them.

Ajay Chhibber is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading:

Image: Police officers stand guard near an inflatable depicting a police officer at a toll station of an expressway after travel restrictions to leave Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province and China's epicentre of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, were lifted, April 8, 2020. REUTERS/Aly Song