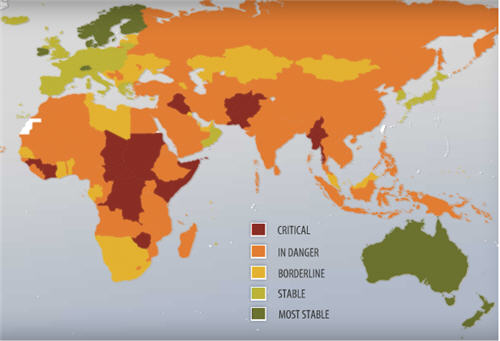

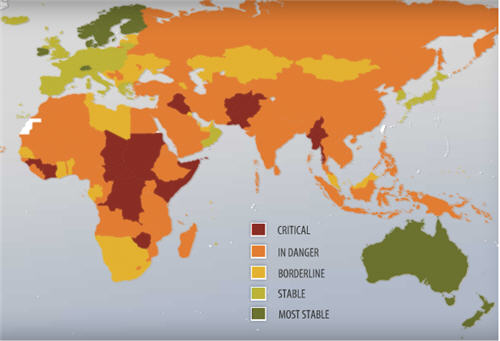

Foreign Policy and the Fund for Peace released the annual failed states index to categorize economic, political, and social stability of the world’s countries. Unsurprisingly, topping the list of most stable and sustainable countries are the Scandinavian countries, Switzerland, Netherlands, Austria, Luxembourg, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.

In spite of the global recession, developed countries are weathering the storm and are not plagued by coup, social unrest, or militarism.

At the other end of the Index are the weakest states that are all too familiar-Somalia, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Chad. War and bad leadership plague these African states, which cannot provide political goods that are expected of modern governments. These include personal security, economic stability, and a functioning bureaucracy to provide for education, trash removal, and transportation services. Iraq fills the #6 spot, but this is a marked improvement from 2007 when it was #2. Iran faltered 11 places to be ranked as #38 in between Tajikistan and Syria. The Index penalized Iran for macroeconomic mismanagement; inflation doubled to 30 percent in 2008. But, as Tehran’s response to the disputed election illustrates, the regime can still control the population, but the trend favors reform.

Historically, countering the Soviet Union or economic interests drove U.S. foreign policy decisions and military deployments. Yet since the 1990s, weak states (or states at risk) have captured the world’s attention that struggle with bringing stability to countries like Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and Afghanistan. Since international institutions are unable or unwilling to develop states at risk, the United States has become proactive to strengthen weak states. Formal acknowledgement came in the 2002 National Security Strategy that noted “America is now threatened less by conquering states than we are by failing ones.” President Obama reiterated this view as a candidate and it will undoubtedly resurface when he releases his national security strategy later this year.

With weak governments unable to control their territory or channel social frustration in non-violent ways, academics and policymakers recognize a need to address states at risk, but there were no good answers. Anthony Lake and Christine Todd Whitman argued, “Neither the United States nor the UN has developed an adequate system for preventing or even containing such calamites [like Darfur] in the future. Article 8 of the Genocide Convention, an injunction to prevent genocide, is the most important responsibility in the convention, much more so than acting after genocide has happened.”

This is likely to get worse.

The National Intelligence Council forecasted within the next decade “weak governments, lagging economies, religious extremism, and youth bulges will align to create a perfect storm for internal conflict in certain regions.” The world is already confronting this in the Horn of Africa as NATO and the European Union combat piracy.

Prioritizing weak or failing states represents a profound shift in strategic thinking. Further, it impacts how developed militaries are changing from forces of confrontation to cooperation. With few exceptions, indigenous security forces are too small, poorly equipped, and ill-trained to effectively monitor and secure their long and remote borders. Consequently, the United States has stepped up its security assistance efforts and finds its military forces in more countries than ever. The forces seldom engage in direct combat operations but are training, equipping, and mentoring partner countries’ militaries. These programs are a part of U.S. grand strategy, which emphasizes military-to-military relations to challenge transnational actors and internal security challenges while strengthening weak states. The effects of this are evident in Colombia, where the United States has helped train and equip the Colombian military to confront its decades-old counterinsurgency against the FARC. There are many ongoing attempts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia.

The emergence of weak states also says something about power. It appears that hard power worked better in a coherent state system and not well in under-governed spaces or with weak states. The Taliban in Afghanistan, warlords in Somalia, and insurgents in Iraq simply do not care that the United States is a military superpower. Ballistic missile defense, space dominance, and fifth generation fighters are irrelevant in conflicts characterized by insurgent cells and improvised explosive devices. Further, there are little direct kinetic military solutions to crises in the Middle East, South Asia, or East Africa. Consequently, the U.S. government has placed renewed emphasis on generating soft power to serve as a reservoir from which to draw non-lethal solutions to U.S. foreign policy problems.

Derek Reveron, an Atlantic Council contributing editor, is a professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, RI. These views are his own. Map: Foreign Policy.

Image: failed-states-index-map-cropped.jpg