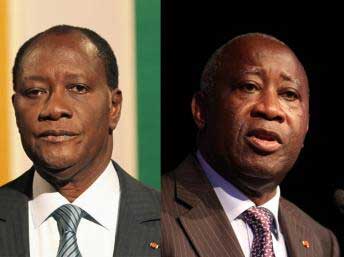

As the Ivory Coast’s former president, Laurent Gbagbo, stubbornly clings to power, his writ confined to a bunker under his house in the commercial capital of Abidjan and surrounded only by his combative wife Simone and a coterie of diehard supporters, the relevant questions are less about the fate of the besieged strongman than what next for his benighted country after nearly a decade of civil war and the protracted dispute over the presidency since the runoff election last November.

While the internationally recognized winner of that poll, Alassane Ouattara, a U.S.-trained economist and former International Monetary Fund deputy managing director who served as prime minister in the early 1990s, can now assume the presidency, he will inherit a bitterly divided country, one whose fissures were, if anything, exacerbated by the manner in which he finally won the power struggle.

Since the 1993 death of its larger-than-life first president, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, the Ivory Coast has been wracked by multiple fierce fights over national identity which are often oversimplified—albeit not entirely inaccurately—into a battle between Muslim northerners and Christian southerners. The conflicts were worsened by the fact that, over the last two decades, various politicians exploited the various fault lines for their own advantage.

Those divisions hardened during the civil war and were, in fact, seen in voting patterns during last year’s elections. While Gbagbo may have lost the race, his share of the vote actually increased from 38 percent to 46 percent between the first and second rounds as he picked up votes from supporters of other southern candidates who did not make it to the runoff. Hence there is a distinct disadvantage with having Ouattara, a Muslim from the north whose opponents even accused him of being from Burkina Faso, come to power thanks largely to the invasion of the south by largely Muslim northerners who make up the bulk of the rebels recently rebranded as “Republican Forces.”

While the Republican Forces broke the four-month-long stalemate by their lightning offensive last week, their contribution to the incoming president’s side raises some serious questions.

First, how much political independence will he have, considering his heavy dependence on the military strength of these units? Ouattara has already had to name the leader of the erstwhile rebels, Guillaume Soro, as his prime minister.

Second, how much control does the new president actually have over these forces? Over the weekend, Ouattara was rather dodgy when confronted by journalists about the reports from church and other civil society groups about atrocities perpetrated by the Republican Forces, including the massacre of nearly 1,000 political opponents in the western town of Duékoué.

The new leader finds himself in an unenviable position. He needs the armed strength of the Republican Forces, especially since he is understandably uncertain of the loyalty of the National Armed Forces of the Ivory Coast (FANCI), most of which backed his opponent until just hours ago when their top three commanders ordered them to cease fighting and surrender their weapons. Yet, at the same time, his reliance on the former rebels is a provocation to citizens in the south in general and the FANCI in particular. In short, Ouattara needs to clearly demonstrate that he is both willing and capable of being a president of and for all Ivorians. One way he can quickly do this is to put together a new government that is more representative of the nation as a whole since, to date, most of his appointments have gone to fellow northerners.

Even after he establishes himself in office, Ouattara faces enormous challenges in getting the country back on its feet again. The Ivory Coast is the world’s largest cocoa producer and accounts for about 40 percent of total global production. Yet for most of this year, exports of the commodity have halted, subject to international sanctions over Gbagbo’s refusal to step down. Now not only does the ban need to be lifted, but Ouattara needs to convince the bureaucracy without whose cooperation moving exports would be impossible, as well as banks and other critical institutions that it safe to once again return to some sort of normalcy. The new administration will also some sort of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration process; the commercial sector that is critical to any reconstruction and sustainable economic growth is simply not going to revive if gangs of armed soldiers, former rebels, and youth running all over the place. There will also be a need for serious security sector reform, beginning with bringing to justice all those responsible for human rights abuses irrespective of what side they took in the conflict as well as the training of an effective professional police force.

The international community, having almost universally backed Ouattara’s claim to the presidency, has a not so insignificant stake in the success of his efforts. It also has an major interest in that further insecurity and the resulting displacement of people—more than one million have already been forced to flee their homes—would threaten the stability of the entire West African subregion at a time that is sensitive enough with the elections in Nigeria and Burkina Faso this month and in Liberia, which has already received more than 120,000 Ivorian refugees in recent weeks, later this year.

Finally, one has to consider the effect of what has happened in the last few days on future peacekeeping operations. While the use of helicopter gunships by United Nations and French forces against a military base, an arms depot, and several heavy weapon systems manned by Gbagbo loyalists may have been justified to prevent their being used against civilians, the action certainly turns the peacekeepers into something other than neutrals in the conflict. What some will see this as a vindication of the “right to protect” (R2P), others will undoubtedly question, as Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov did on Tuesday. Thus there may be the unintended effect of the greater reluctance on the part of some members of the Security Council to authorize future missions for fear that they may stray from a narrow interpretation of their mandates. And, most certainly, other leaders will be reluctant to voluntarily admit a UN peacekeeping force into their country—as Laurent Gbagbo did in 2003—if they think that it might eventually turn on them.

J. Peter Pham is Director of the Michael S. Ansari Africa Center at the Atlantic Council.

Image: ouattara-gbagbo2.jpg