First, the good news: A growing availability of COVID-19 vaccines has cast a light at the end of the pandemic tunnel. But after a year of the pandemic’s ravages on human health and economic activity, it is important to take stock of how the international community has coped with the development, production, and distribution of vaccines—and to draw lessons for the future. And that’s where the bad news comes in: The world’s experience so far with COVID-19 vaccines has not been very uplifting.

The COVID-19 vaccine coalition COVAX, sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO), has highlighted the need for global cooperation. But countries are simultaneously competing to secure vaccines still in limited supply, prioritizing their own population over others, imposing various forms of export controls on vaccines and the ingredients used for their production, and engaging in vaccine diplomacy to gain diplomatic and geopolitical influence. As the United Nations secretary general has pointed out, for example, as of February only ten countries had administered 75 percent of all vaccinations.

The situation will slowly improve in the future as more vaccines are produced and start to trickle down to low-income countries. But the message is clear: Rich countries will take care of themselves first, while those that ship vaccines to other countries will do so to build up their international clout. This reality doesn’t augur well for the world’s ability to deal with the next pandemic.

Novel vaccines for a novel coronavirus

One bright spot in an otherwise bleak picture of international cooperation was the sharing of genomic data related to COVID-19, especially at the beginning of the pandemic before political bickering and mistrust got in the way. This helped scientists in many countries to develop various types of vaccines in record time—within months instead of years, as has traditionally been the case with vaccine development.

Nevertheless, two related problems continue to jeopardize the ability of vaccination to help sufficient areas of the world achieve herd immunity—and thus bring the COVID-19 pandemic to a point where it can actually be deemed over. One is persistent skepticism and reluctance to take vaccines, which varies significantly across countries, ranging from 15 percent of the population in some countries to roughly 50 percent or more in others. The second challenge is skepticism about the safety and efficacy of vaccines because of a perception that political pressures accelerated the development and authorization of vaccines (pressures expressed, for instance, in tweets by former US President Donald Trump) or that early national authorization of vaccines failed to disclose adequate data from trials (for example, in the cases of Russia’s Sputnik V, which was approved even before phase III trials, India’s Covaxin, which was approved for emergency use while trials were still ongoing, and China’s Sinopharm and Sinovac, which have not released all data). Even though satisfactory results of phase III trials of Sputnik V were later published in a peer-reviewed article in The Lancet, more than 60 percent of Russians have been reluctant to get the vaccine.

Uneven distribution of vaccines

Despite the skeptics, vaccine producers globally have accelerated COVID-19 vaccine production. According to the science-analytics company Airfinity, as of mid-March, China had produced 169 million doses; the United States, 136 million doses; the European Union (EU), 96 million doses; India, 68 million doses; the United Kingdom, 19 million doses; and Russia, 11.8 million doses. Vaccination has also begun in earnest since the beginning the year, with more than 447 million shots given across 133 countries.

But the pace of vaccination has been very uneven. A few large countries have made impressive progress in putting at least one dose of vaccine in the arms of their population: for example, as of this writing, Israel has at least partially vaccinated 57.1 percent of its population, the United Kingdom 41.4 percent, Chile 29.3 percent, and the United States 24.5 percent (though the United States leads in total numbers of shots at about 124 million). Others have lagged far behind: The EU has given at least one dose to just 8.7 percent of its population, Russia 3.4 percent, and India only 2.7 percent. Many developing countries, especially in Africa, have yet to get any shots—despite the fact that COVAX has shipped over 30 million doses of vaccine to fifty-two lower-income countries. COVAX has received pledges of contributions from governments, corporations, and foundations totaling $6.3 billion, including $2 billion from the United States after the Biden administration joined the vaccine coalition. Yet these pledges have not yet amounted to shots in the arms of many countries that need them.

The differentiation in stockpiling vaccines has also been stark. A few countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada have secured purchase agreements on more than enough doses for their entire population but have not yet exported vaccines to other countries. The United States has tens of millions of unused doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, which the Food and Drug Administration has yet to authorize and which thus cannot currently be used in the United States. Washington has agreed to ship some of these doses to Mexico and Canada but has refused to share that inventory with the EU, where the vaccine has been authorized and used as the bloc’s main vaccine.

The EU vaccination program, for its part, has recently run into production delays, and use of the AstraZeneca vaccine was temporarily suspended by several member countries due to fears that it may cause blood clots. Countries lifted the suspension after the European Medicines Agency declared that the vaccine is safe, and the AstraZeneca vaccine remains a vital part of Europe’s vaccination plans, but the events have nevertheless contributed to skepticism about the vaccine. The production shortfall of the AstraZeneca vaccine has also led to bitterness between the United Kingdom and EU, with the latter accusing the United Kingdom of blocking vaccine exports and threatening to withhold its own exports to the United Kingdom. Many countries, moreover, have practiced vaccine nationalism by prioritizing their own populations ahead of others, with or without formal export controls.

In addition, interferences in cross-border supply chains due to export controls have hampered vaccine production in some cases, given the need to source various ingredients for vaccine production from many different countries. Moreover, several developed countries have refused to join a majority of World Trade Organization members in agreeing to requests by India and South Africa to temporarily waive patent protection of COVID-19 vaccines so that they can be produced generically and thus facilitate the timely and globally equitable distribution of vaccines.

Vaccine diplomacy

By contrast, three countries have stood out for sending vaccines to many developing countries—vaccines that they aren’t fully using at home for various reasons.

In Russia, popular reluctance to take the Sputnik V vaccine may help explain why Russia has been in a position to supply vaccine doses to several European countries such as Hungary and Serbia, helping them achieve higher rates of vaccination than EU averages, along with other countries such as Argentina.

China appears to be implementing a slow domestic rollout of vaccines while sending 60 percent of its production of Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines as aid to fifty-three countries and exports to twenty-seven, according to government reports.

India, facing logistical problems that have slowed its vaccination effort, has sent 65 percent of its production of Covaxin and Covishield (produced in India under license from Oxford-AstraZeneca) vaccines to other countries, mainly in South Asia. To counter China’s vaccine diplomacy, the leaders of the United States, India, Japan, and Australia announced during their first virtual Quad Summit that they would supply one billion doses of vaccine to Indo-Pacific countries by 2022—by scaling up production in India in an effort financed by the other three members of the bloc. This will certainly be welcomed by recipient countries, but it is clear that it takes place in the context of great-power rivalry.

While many observers believe Russia, China, and India are engaging in vaccine diplomacy to advance their influence, the recipients of that diplomacy probably view the vaccines as better than no vaccines. What’s more worrying is that widespread use of vaccines that don’t go through transparent and sufficiently rigorous testing, trials, and authorization processes may undermine global standards set by the WHO, contributing to persistent skepticism of vaccines in general and risking medical mishaps in the future.

Implications for the next pandemic

Vaccine nationalism and competition, on top of the international acrimony over China’s early handling of the viral breakout and lackluster cooperation to investigate the origin of COVID-19, have contributed to a delay and lack of coordination in the global rollout of vaccines. A recent UBS report estimates that at current rates, only 10 percent of the world population will be vaccinated by the end of 2021, rising to 21 percent by 2022. Such a slow and uneven distribution of vaccines will prolong the pandemic, costing up to $9.2 trillion, according to the International Chamber of Commerce. Populist pressures in the domestic politics of many countries and mistrust and strategic competition among major powers suggest that the uncooperative behaviors mentioned above are unlikely to change in the future.

This does not bode well for the world’s ability to deal with the next pandemic, which is a matter of when, not if. In addition to the ten infectious diseases for which there is currently no licensed vaccine or cure—including the Marburg, Lassa, Zika, and Nipah viruses as identified by the vaccine alliance Gavi—a team of scientists in China recently discovered twenty-four new bat coronaviruses with surprising genomic diversity within a two-kilometer radius. Any of these viruses or a completely novel one, with sufficient mutations, could trigger another viral outbreak that could quickly become another pandemic.

The grave risk facing the world is not that another pandemic will occur, but rather that when it inevitably occurs the world will react in the same way it has to COVID-19. It is thus important for publics to pressure their governments to learn from today’s lessons and strive to do better in the future.

Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance, and former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund.

Further reading

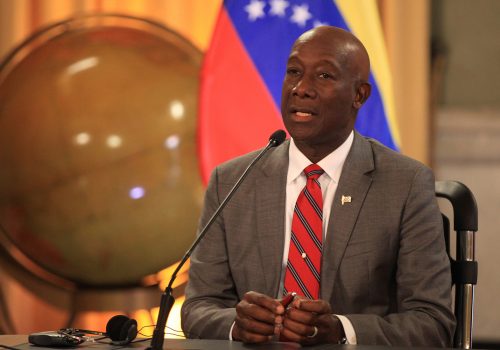

Image: In the photos taken on March 16, 2021, it shows a vaccination center against the coronavirus in Colombia. ULAN/Pool / Latin America News Agency via Reuters