Where is the US still leading on democracy? Look beyond the government.

In the months after NATO-backed rebels toppled the government of Muammer Gaddafi in Libya in 2011, few Westerners other than journalists, aid workers, and a smattering of business people dared travel to the chaotic country. And then there was the contingent from US-based, congressionally funded organizations such as the National Democratic Institute and the International Republican Institute, who were in Libya to help the country’s nascent civil society lay the foundations of a possible democratic future.

The NDI folks were particularly active. As a foreign correspondent in Libya during those days, I would not have been surprised to run into Les Campbell, who is still at NDI, or Megan Doherty, now at Mercy Corps, driving with minimal security from city to city, offering workshops and training for Libyan activists and aspiring politicians, or organizing talks where Libyans would speak to each other about what they wanted and expected from their fellow citizens and leaders.

Libya’s story doesn’t have a happy ending. The North African country fractured politically, igniting a civil war and creating an opening for ISIS. Nevertheless,when reporting some years later on a particularly vicious ISIS attack on the country’s election commission, I encountered several people who were veterans of such democracy programs. While much of the country had descended into chaos, these proud Libyans had been quietly working behind the scenes to bring about a measure of normalcy and stability through the power of the democratic vote. And they had all benefited at some point, directly or indirectly, from Americans’ willingness to share their experiences with the democratic process. As recently as October, NDI staff in Libya were holding workshops for politicians and party activists to discuss local and national elections and a referendum on a new constitution.

While much of the country had descended into chaos, these proud Libyans had been quietly working behind the scenes to bring about a measure of normalcy and stability through the power of the democratic vote.

These aren’t exactly boom times for democracy. It is, in fact, on the ropes around the world. During a talk in Morocco I moderated last year, scholars and former government officials from Africa and Asia spoke approvingly of the authoritarian models touted by Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping. In former Communist and Soviet nations, corrupt authoritarians are twisting and turning laws to erode press freedoms and manipulate elections to their advantage. Hungary, a member of the European Union and NATO, is fighting with the European Union over measures enacted under Prime Minister Viktor Orban that threaten the rule of law. The flowering of democratic aspirations in the Middle East and North Africa following the 2011 Arab uprisings has mostly wilted away under the boot of military strongmen. Even the United States has flirted with lawless, authoritarian-tinged rule under Donald Trump, who has explicitly sought to manipulate the results of the 2020 presidential election by baselessly and repeatedly claiming fraud.

But as the long lines to vote and record turnout in this year’s election underscore, democracy remains a core part of the American brand. And under a President Joe Biden, the United States will have an opportunity to reinvigorate embattled democratic practices and values across the world.

As the long lines to vote and record turnout in this year’s election underscore, democracy remains a core part of the American brand.

“My sense is that the West has lost the moral high ground in the last four years,” says Tara Varma, a Paris-based scholar at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “Our model is a lot less attractive. It’s not the gold standard any more. Even authoritarian regimes don’t want to pretend that they’re democratic any more. What Europe and the US need to do is to fight to win the cultural battle.”

Despite its arrogance, blunders, and own flaws, and despite Washington’s history of using the issue of democracy as a cudgel against governments it doesn’t like, the United States still has an important leadership role to play in promoting little “d” democratic values—especially with China and Russia actively promoting their authoritarian models. People guffaw nowadays when the US State Department issues a statement condemning election irregularities in another country. But more important than US government pronouncements are the scores of American organizations doing on-the-ground work to build up transparency and good governance around the world—entities and initiatives that a new US administration could champion and make central to America’s retooled role in the world.

Campbell tells me that their work isn’t about imposing a US (or, for that matter, Swedish or German) model of democracy on developing countries, but rather about drawing on the experiences of former Soviet states and Middle Eastern nations like Tunisia, the only success story so far of the 2011 Arab uprisings. Much of the work is modest, such as helping small political parties organize for municipal elections.

“We’re really not looking at the experiences of the established Western democracies,” says Campbell. “We’re relying more on the experiences of other countries that have gone through transitions.”

Then there’s the American Bar Association’s Rule of Law Initiative, which operates in regions such as Africa and Asia and attempts to assist with judicial-reform efforts. Even during the pandemic, it has been training African Union officials on how to better advise member governments and legal personnel in the Philippines on how to defend their clients.

Far-right operatives and authoritarian regimes of all stripes often vilify George Soros’s complex of groups promoting peaceful democratic transitions and practices. But on the ground, in struggling democracies such as Bulgaria, Georgia, and Ukraine, groups and initiatives funded or founded by his organization are often the most vocal advocates of liberal, democratic values. They pursue decent prices for pharmaceuticals in Eastern Europe, hold workshops for dissidents living under autocratic regimes, promote the power of non-violent protest, and support think tanks that fund research into government corruption.

There are, of course, also non-US organizations that do such work and often collaborate with their American counterparts, including Germany’s Democracy Reporting International, the United Kingdom’s Westminster Foundation for Democracy, and the multilateral International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. IDEA helps struggling or emerging democracies draft constitutions, build up the capacity of political parties, and ferret out the influence of money in politics and elections.

Unlike Canada, Mexico, Australia, and much of Europe, the United States is not one of IDEA’s thirty-three member states. The most recent country to join was Tunisia, which in 2019 became the group’s first Arab member. The Biden administration could give both the organization and democracy a big symbolic boost, and show that America’s brush with authoritarianism is over, by becoming a full-fledged member state.

It’s never a good idea to attempt from abroad to impose democracy on another country. But it is a good idea to nurture democracy by learning from other countries’ successes and failures.

It’s never a good idea to attempt from abroad to impose democracy on another country. But it is a good idea to nurture democracy by learning from other countries’ successes and failures. Tunisia, to cite just one example, has developed a parallel-vote tabulation system that has proved accurate in counting votes to within 0.1 percent of the final results and could be adopted by US states. “That would shut up all the people calling fraud,” Campbell says. And it’s a good idea to engage in gentle democracy-promotion efforts that constitute a critical lifeline in places like Yemen, where subterranean initiatives to bolster civil society continue despite ongoing wars.

“What’s the alternative? Nothing else exists like this,” Campbell says of the small group of organizations promoting democracy on the ground around the world. “Whether we have given up on them or not that’s not how the citizens of these countries feel at all. They think they’re in the middle of the fight. Every day groups in Yemen get together amid the threats and discuss what comes next. They don’t think it’s over. We shouldn’t think it’s over either.”

Borzou Daragahi is an international correspondent for The Independent. He has covered the Middle East and North Africa since 2002. He is also a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Security Initiative. Follow him on Twitter: @borzou.

Further reading:

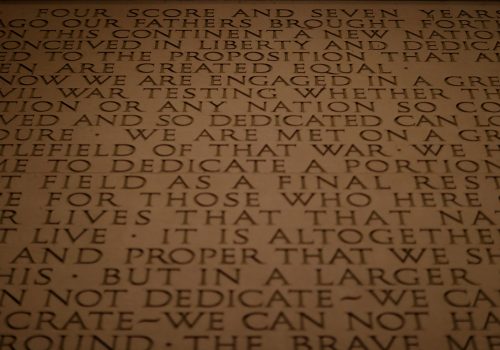

Image: A group of members of the Central Committee for Municipal Elections are seen during an election simulation in local school, Tripoli, Libya February 3, 2019. Picture taken February 3, 2019. REUTERS/Hani Amara