The Atlantic Council’s Robert Manning recently focused our attention on the October Asia-Europe Summit in Beijing. We Americans might have missed the significance of the emerging multipolarity and shifts in global power while up to our elbows in election politics and financial woes.

Another meeting that evaded our attention took place October 29-30 – the ministerial of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in Kazakhstan. Made up of Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, with observers India, Iran, Mongolia and Pakistan, the SCO is seen by many as a counter to the U.S. and NATO in the region. Created in 2001 by expanding the Shanghai Five that was established in 1996 to solve border disputes, the SCO is moving into new arenas. In October, its members pushed ahead on economic and financial stability goals, along with energy security and improved border cooperation. As reported in Eurasia Insight, “Russia used the SCO talks in Astana … to urge a shake-up of the global economic and security order.” Xinhua wrote that China also backed closer economic cooperation within the SCO to enhance coordination of monetary policies and improved financial controls.

Russia and China clearly see the SCO as an opportunity for energy development and control in Central Asia. The initiatives on the table include an Asian Energy Strategy and SCO Energy Club to define joint projects on a unified energy market and common transport corridor. It wouldn’t take much to expand upon the existing pipeline system linking Russia, Central Asia and China. The former Soviet “stans” are not heavy energy hitters at the moment, but add in the SCO observers India and Iran and the options expand enormously.

Speaking of Iran, Russia and China both met with its First Vice-President, Parviz Davoudi, around the edges of the SCO session to discuss their major commercial interests there, including energy. Russia needs Iran’s support to exploit Caspian Sea energy resources (neurope.eu), while Iran wants to expand its relations with the SCO member states. These ties are moving forward in an environment largely absent the U.S. and the West.

The SCO is not a rising security threat that we need to counter. Rather, we should be aware of the enhanced relations among these countries and identify where we can advance our own continuing interests. Neither is it a solid bloc. We last heard about the SCO in September when Russia attempted to get member states’ to recognize South Ossetia and Abkhazia … and was turned away empty-handed. One could argue that any organization with two giants like Russia and China will always be limited by frictions between them. Despite so much rhetoric about cooperation, it remains to be seen whether the SCO can implement concrete projects.

Furthermore, legitimate concerns among Central Asians demand that they work together, especially to foster regional security in the face of growing extremism, terrorism and criminal structures, as noted by Kazakh President Nazarbayev. SCO members discussed the need to become more involved in assisting Afghanistan, which could ultimately help our cause there. However, as the Russian Federation takes over the presidency of the SCO for the year ahead, the new U.S. administration along with our European and Asian partners should keep an eye on Central Asia and its two colossal bookends.

Lynn Roche is Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council and Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State.

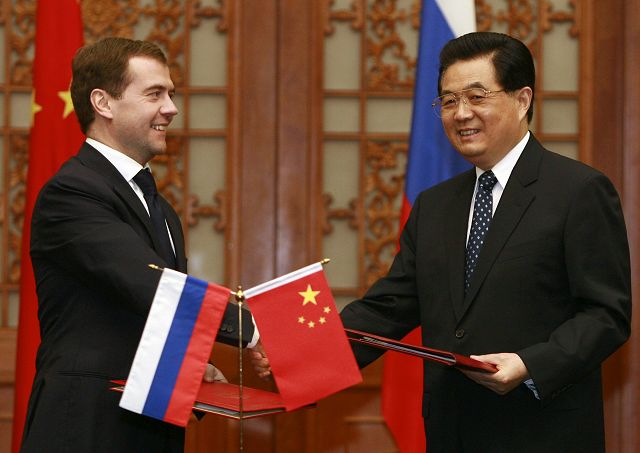

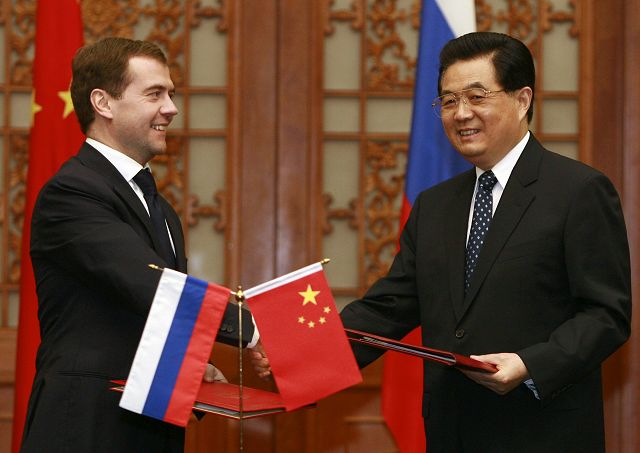

Image: MedvedevHu.jpg