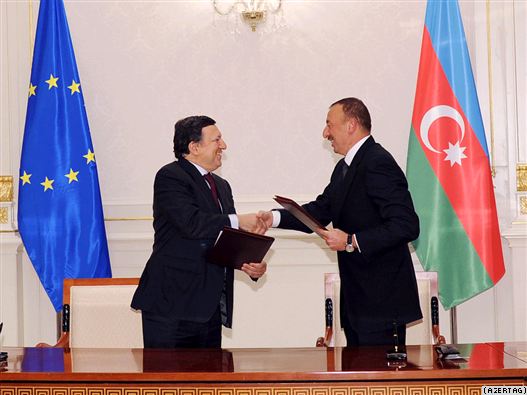

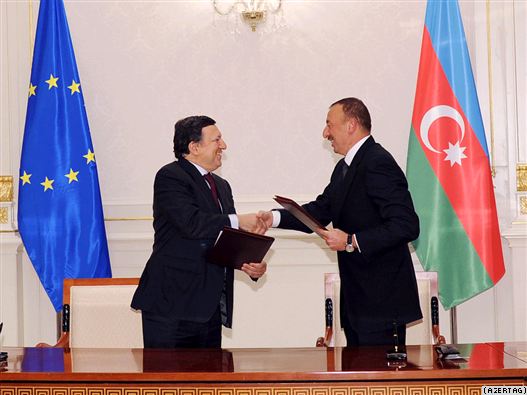

European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso was in Turkmenistan last week negotiating ways the Caspian country’s vast natural gas reserves might ameliorate European dependence on Russian resources through the so-called Southern Energy Corridor. Coming on the heels of a successful agreement inked in Baku to bring Azerbaijani gas to the European Union, Barroso’s meeting in Ashgabat instead indicated the need for more talks in the coming months.

It has long been conventional thinking in the West to see Turkmenistan as ‘a bridge too far.’ Though European leaders have longed for access to Turkmenistan’s 8.1 trillion cubic meters of proven gas stores, substantial impediments to any southern corridor project have prevented the opportunity to connect European consumers with Turkmen producers. However, Ashgabat’s decision to diversify away from Russia and China by shaking hands on the TAPI pipeline to Pakistan and India, and the expression late last year of their willingness to construct a trans-Caspian pipeline that could connect to a project supplying Europe, have put the concept of a southern corridor firmly back on the table. European decision makers must react quickly to this opportunity, but must also press for the adoption of the most logical project.

There have traditionally been a number of factors preventing the construction of a pipeline from Turkmenistan to Europe: the country is often thought to be simply too far away, given the technical restraints on the length of pipelines and the difficulty in crossing the Caspian; Turkmens have often been reluctant to negotiate with European leaders, and; the ongoing dispute between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan over ownership of the off-shore Serdar/Kyapaz gas field has prevented cooperation between the two nations.

These obstacles have led to suggestions for Iraqi, rather than Turkmen gas, to be linked into the southern corridor. Moreover, the completion of the 1,139 mile China-Central Asia pipeline, which connects China’s Xinjiang province with Turkmenistan, has led many to assume that Ashgabat would concentrate on strengthening its ties to Beijing’s enormous market, at the expense of Europe. However, developments in recent weeks suggest that Turkmenistan may be on the way to overcoming many of these obstacles. The agreement to construct the 1,700 km TAPI pipeline, connecting the gas rich field of Dauletabad in southern Turkmenistan to the expanding markets of Pakistan and India, is a hugely ambitious project given the need to pass through the unpredictable provinces of Helmand and Kandahar in war-torn Afghanistan. Though the pipeline cannot be built until the security situation in Afghanistan improves, the deal demonstrates Ashgabat’s determination to diversify away from Russian and Chinese demand.

Secondly, after years of ambiguity or silence, the Turkmen government has finally expressed its willingness to work with Azerbaijan on the construction of a trans-Caspian pipeline, which could link up to a project transporting gas to the huge European market. In November, both the president and deputy prime minister expressed their willingness to supply Europe with as much as 40 billion cubic meters, or bcm, of gas annually via a pipeline crossing the Caspian and South Caucasus.

Though these proposals remain far from concrete, they do place the three primary southern corridor projects back in the spotlight. The largest of the three, the Nabucco pipeline, aims to deliver 30 bcm of gas to Europe, beginning in Turkey and finishing in Austria; the Italy-Turkey-Greece Interconnector, or ITGI, is the smallest solution to opening the southern corridor with a capacity of less than 10 bcm; while the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, which aims to transport gas from the Caspian to Albania, Greece, and Italy, is the shortest pipeline, with a flexible capacity of around 20 bcm. Its plans also allow for the reverse flow of gas, an important option in case of future gas cutoffs, such as those experienced in Eastern Europe in 2008. Perhaps most importantly, however, a project the size of Trans-Adriatic does not – at least initially – require gas from anywhere other than Azerbaijan. Southern corridor construction can begin as negotiations with Turkmenistan continue.

Though the Nabucco project is undoubtedly the most discussed of the three, this does not mean it will necessarily win out. In fact, given the timeframe the Turkmens are implying (completion by 2015), it appears more likely that a smaller project will be adopted. This needs to be recognized by European decision makers, who should be pushing for the most realistic proposal to be agreed upon as soon as possible. While the Turkmens are currently interested in the southern corridor, the rapidly changing nature of Eurasian energy geopolitics in recent years ensures that there are no guarantees this enthusiasm will persist. Furthermore, given the uncertain prospects of the TAPI project, it would make sense to undertake a more stable mission in the southern corridor. For these reasons, European decision-makers should perhaps more seriously consider the medium sized Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, which is the most cost effective of the three projects and has the added ability to expand its capacity relatively easily.

Richard Morningstar, the United States’ Special Envoy for Eurasian Energy, recognized these developments in his recent suggestion that Nabucco is “not the only project” worth considering.

The southern corridor is both a vital source of energy for the expanding European gas market and a potential political asset in countering the dominance of Russia and China. Turkmenistan’s changing attitude provides an opportunity that cannot be missed, but Western decision-makers should take advantage of it prudently and support the project that makes the most sense.

Alexandros Petersen is senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and director of research at the Henry Jackson Society. This article was originally published in the Hurriyet Daily News & Economic Review. Photo credit: Azertag

Image: 387F7B06-DACB-4203-B5B0-AAB9B823D21F_w527_s.jpg