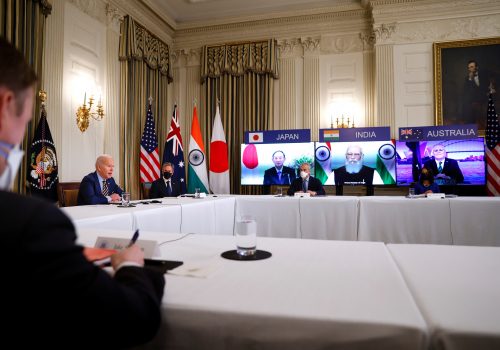

For the Biden administration, reeling from a spate of recent foreign-policy setbacks, last week’s Quad summit at the White House refocused attention on a key US priority: strengthening alliances amid the greater strategic competition between democracy and autocracy.

Following the summit, US President Joe Biden and prime ministers Yoshihide Suga of Japan, Narendra Modi of India, and Scott Morrison of Australia issued a joint statement affirming their shared values and commitment to defending an open, rules-based order. While its specific outcomes—agreements to cooperate on COVID-19 vaccines and bolster semiconductor supply chains, as well as to establish a student scholarship program—were relatively modest, the summit successfully laid the foundation to advance three strategic goals: countering China, aligning India, and revitalizing alliances.

1. Countering China

The summit amplified a consensus among US allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific on the need to stand up to Beijing, signaling that members are prepared to act collectively to safeguard the rules-based international order. While not explicitly mentioning China, Quad leaders emphasized their shared commitment to “the rule of law, freedom of navigation and overflight, peaceful resolution of disputes, democratic values, and territorial integrity of states”—all pointed references to areas in which Beijing is seeking to challenge the status quo.

The meeting clearly rattled Beijing: A spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry denounced the Quad, saying the formation of “exclusive closed cliques” run against “the trend of times” and would find “no support.” The emphasis on technology cooperation—particularly regarding semiconductor supply chains—could provide the group with increased salience as its members seek to gain an edge in a critical area of strategic competition with Beijing.

2. Aligning India

The summit also reinforced India’s gradual foreign-policy shift toward the United States and the West. For decades, New Delhi has clung to its non-aligned status, displaying a reluctance to take sides amid great-power rivalries. But in recent years, its strategic posture has begun to evolve. The fact that Modi chose to participate in such a high-profile summit alongside the leaders of other leading democracies shows how far India has come in terms of its global orientation. In his remarks, Modi emphasized “shared democratic values” and the role of the Quad as a “force for global good.”

Still, while its interest in countering China has brought it closer to the West, India continues to hedge, maintaining close political and military ties to Russia despite Moscow’s efforts to undermine Western democracies and expand its burgeoning strategic axis with Beijing. Much more will be needed to cement India’s emerging realignment. The summit’s early focus on vaccine cooperation and technology supply chains could prove significant over time, building habits of cooperation on discrete issues while also giving India’s domestic industries a greater stake in the success of the Quad.

3. Revitalizing alliances

With its images of Indo-Pacific leaders standing together in the face of a common strategic challenge, the summit provided a dramatic counterpoint to those suggesting the United States is no longer willing to lead. In the aftermath of the Afghanistan withdrawal and the fallout from the AUKUS deal in which Australia cancelled an agreement with France in order to buy US nuclear-powered submarines instead, the summit demonstrated that Washington remains prepared to work closely with allies and take on global challenges. But with Europe left out of the mix, the summit also risked playing into perceptions, amplified by AUKUS, that the administration was sidelining its traditional European partners. Europe is clearly eager to engage in the Indo-Pacific: British Prime Minister Boris Johnson reportedly even raised the prospect of joining the Quad. While they may harbor differing perspectives, it is in the United States’ interest to engage transatlantic allies on a common approach to China, even as it seeks to deepen cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners.

The Quad acknowledged Europe’s interests in the region, stating that it “welcomed” the European Union’s recent strategy proposal for the Indo-Pacific. But the United States should resist efforts to expand the group. Its cohesive membership, based upon democracies with a geographic nexus and strong shared concerns over China, is advantageous, and rapid expansion could complicate efforts to make progress on specific issues. Instead, the Biden administration should establish a separate coalition that brings together core transatlantic and Indo-Pacific democracies under a common umbrella to formulate a joint approach to advance a free and open Indo-Pacific. The concept of a D-10—which Johnson raised last week during his White House meeting with Biden—could be attractive as a means to bring such a coalition to life.

Coming on the heels of the Malabar naval exercises near Guam in August, which included forces from Quad nations, the message is clear: The United States and its Indo-Pacific partners are moving rapidly to ramp up cooperation across a range of domains—from health, climate change, and trade to technology, security, and defense—to counter a rising China.

Whether it can produce meaningful cooperation in specific areas remains to be seen. But the Quad has come a long way since its inception as a nascent security dialogue in 2007, and the summit succeeded in cementing the group as a key component of US strategic engagement in the Indo-Pacific.

Ash Jain is director for democratic order with the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and a former member of the State Department’s policy planning staff.

Further reading

Image: US President Joe Biden hosts a 'Quad nations' meeting at the Leaders' Summit of the Quadrilateral Framework with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Australia's Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and Japan's Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga in the East Room at the White House in Washington on September 24, 2021. Photo by Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters.