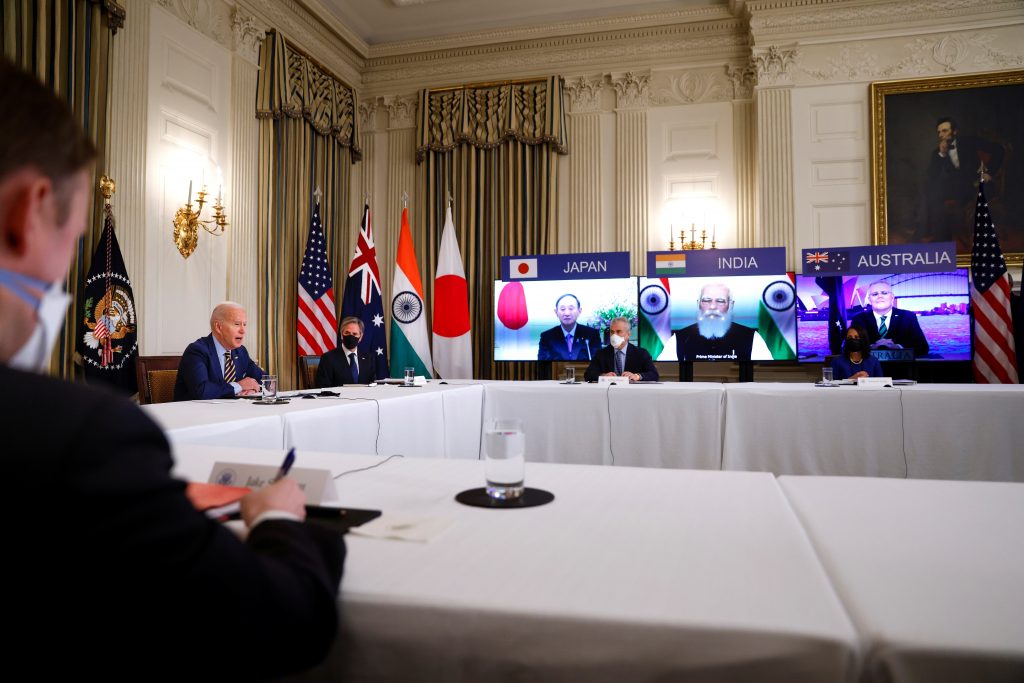

US President Joe Biden is set to host a first in-person Quad meeting on September 24, 2021, with Australia, India, and Japan present. South Asia Center experts react to the meeting and offer insight into what to expect.

A critical component for global and strategic policy frameworks

This Quad meeting at Leaders level should be an important moment in cementing each country’s political commitment to elevation of the Quad as a key component of their global and strategic policy frameworks. Even with a Japanese delegation distracted by the lame duck status of Prime Minister Suga, the session should be important in marking progress in its subgroups and setting the agenda going forward. However, the Quad provides no substitute for maintaining strong trade relationships, which will continue to be pursued on a bilateral basis. Perhaps Japan and Australia will face the greatest challenges in reconciling their bilateral trade relationships with the United States and India and their regional partnerships in CPTPP and RCEP. For all the talk of Indo Pacific trade initiatives, presumably excluding China, such as a future digital trade arrangement, there appears to be very little meat on the bone. Trade observers will have to temper their short-term expectations, including hopes that the U.S.-India trade relationship might eventually gravitate towards a moderate upgrading, which would still fall far short of relationships the United States has with much of the rest of the region.

Mark Linscott is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. He served as the assistant US Trade Representative (USTR) for WTO and multilateral affairs from 2012 to 2016, with responsibility for coordinating US trade policies in the WTO, and as the assistant USTR for South and Central Asian affairs from December 2016 to December 2018.

Unclear objectives undermine the QUAD’s potential

QUAD’s objectives are yet to be fully known. Such ambiguity does not project a good signal because many political observers are simply viewing it as an anti-China alliance, which undermines its potential in other essential areas such as climate change issues and vaccine diplomacy. The viability of the QUAD also depends on the support and cooperation of other countries located in the Bay of Bengal basin. If the QUAD ever expands, it is doubtful whether countries in the Indo-Pacific region would join it willingly, especially given their deep trade relations with China. For example, earlier this year, Bangladesh had suggested that it does not wish to join the initiative. This assertion was followed by warning signals by the Chinese Ambassador in Dhaka in case Bangladesh ever wishes to do so. Making the QUAD attractive to other countries means that what they gain from such a partnership must be clear to them, especially in the economic domain. More importantly, future partners must be convinced about what the implications are going to be in case of significant geopolitical changes. While NATO faces challenges, the alliance still remains, while other such security alliances such as the SEATO and the CENTO cease to exist. In such a scenario where security alliances come to an end, how are member states affected? Such questions need to be addressed for getting support from more countries in the region.

Moreover, the inauguration of the AUKUS in the past week—a security pact between Australia, the UK, and the USA—brings up questions about the normative and practical significance of the QUAD. While some sections of media from the QUAD members who are not part of AUKUS, namely India and Japan, have welcomed the advent of the AUKUS, others have not as they are questioning whether a new pact is intended to sidelines the QUAD. ASEAN members, who had earlier shown support for the QUAD, have expressed their concerns over the potential of sparking a nuclear arms race in the Indo-Pacific region. France has recalled its Ambassadors from Canberra and Washington DC, citing its displeasure at the cancellation by Australia of a $90 billion bilateral submarine deal without prior notification that it would be acquiring nuclear submarines from the United States after joining the pact. So, in the long run, can there be a scenario where policymakers in India and Japan start thinking about whether the United States is trying to dominate the global maritime domain without considering the interests of their security partners?

Rudabeh Shahid is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Reaffirming a Free and Open Indo-Pacific

At the historic QUAD Summit, the leaders of the United States, Japan, India, and Australia will send a powerful signal that the Free and Open Indo-Pacific still has champions. In recent years, ample ink has been spent cataloguing the shifting power dynamics in the Indo-Pacific in the wake of China’s rise. The Quad and the new AUUKUS partnership suggest new alignments are rising and cohering to meet this common challenge. Expect Beijing’s shadow to loom large over the meeting, even as the leaders aim to avoid billing the Quad Summit as an explicit “anti-China” coalition. Central to this strategy is widening the aperture of the Quad to tackle common challenges such as the coronavirus, supply chain resiliency, and emerging technology cooperation. Yet if the Quad Leaders Summit is to be meaningful, it must yield substantive outcomes and initiatives, not just high-level rhetoric. High on the wishlist of diplomats and observers are concrete announcements on semiconductor manufacturing as well as alignment on emerging technology standards for 5G telecoms. Pledges by India to boost COVID-19 vaccine production and exports would also serve as important outcomes.

Anand Raghuraman is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and a vice president at The Asia Group, where he advises leading companies operating in South Asia across the internet, e-commerce, social media, fintech, and financial services sectors.

A reinvigorated Quad is becoming a key element of the new US administration’s Asia policy—just not in the way you expected

A reinvigorated Quad is becoming a key element of the new administration’s Asia policy. The four national leaders convened virtually in March amid multiple global crises. They wisely decided to focus on concrete ways to deliver for their people and the region. The group sought to prove that democracy still works, as President Biden likes to say. The Quad Leaders’ communique set the bar high: cooperation on “the defining challenges of our time.”

Largely across U.S. party lines, the consensus is building that China’s economic and military aggression ranks high among the defining challenges. But rather than construct an anti-China military alliance, the Quad has so far opted for a pragmatic and unifying focus on urgent global problems. That decision in part acknowledges India’s reluctance to antagonize China, especially while their border dispute remains unresolved. The smaller ASEAN countries and, to a lesser extent, even linchpin U.S. ally South Korea, are wary of being jostled about by major power competition. More fundamentally, the region is keen to tackle pressing issues like the pandemic and climate change.

The Quad partners will also discuss progress related to critical and emerging technologies—now a significant dimension of preserving free and open societies. They will exchange views on reducing escalating tensions over the Taiwan Strait and addressing the tragedy unfolding in Myanmar. While defense ties are not the leading edge of the Quad, the leaders may not pass up the opportunity for discrete conversation about Western Pacific and Indian Ocean security.

The Quad and likeminded democracies are all eagerly exploring overlapping security arrangements in response to a shifting power balance. While they do so, it is vital that as liberal societies, they take the necessary steps at home to secure democratic institutions against the polarizing forces of nationalism, populism, and xenophobia. That will only make the Quad and other coalitions stronger.

Atman Trivedi is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and has over twenty years of foreign policy and trade experience with expertise in India and the broader Asia region.

Read Atman Trivedi’s full article here

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

Image: U.S. President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, not pictured, participate beside staff and cabinet members in a virtual meeting with Asia-Pacific nation leaders at the White House in Washington, U.S., March 12, 2021. REUTERS/Tom Brenner