Advanced technological solutions are not limited to technologically advanced societies. Numerous examples in Syria show the use of innovative solutions for real world problems using open source technology: 3D printed prosthetics for amputees, renewable energy in cities under siege, and now aquaponics in damaged farmlands. The use of smart agriculture can help provide for people’s essential nutrition needs, especially in conflict zones, where food insecurity is prevalent and underserved farming opportunities are common.

In 2016, Sameh was looking for ways to help Syrians return to their farms. With an agricultural engineering father, farming has been part of Sameh’s world since childhood. A friend of his introduced him to an open-source electronics platform based on easy-to-use hardware and software called Arduino.

With further research, Sameh came to a farming system called hydroponics, which showed better yield than traditional farming, especially in areas with a lack of water. Eventually, Sameh settled for aquaponics, because it presented a higher nutrition value, with the presence of the fish protein, and less chemical input.

Sameh, a thirty-six-year-old man from Damascus, traveled throughout Kurdish territories in northern Syria from June to July 2018 to scout a location for an aquaponics prototype to support local communities. The trip served as a starting point in accessing the needs and resources available in order to create a customized model to develop. Along with a few friends, he hopes to expand the use of the prototype across the region and the state to sustain civilians living through the conflict and Syria’s rebuilding in the long term.

What is aquaponics?

Aquaponics is the combination of aquaculture, the process of raising aquatic organisms, and hydroponics, the cultivation of plants without soil, in one integrated system. The waste from the aquatic organisms provides an organic food source for the plants. In combining both hydroponic and aquaculture systems, aquaponics utilizes fewer resources and produces more food.

Traditional, soil-based agriculture in Syria requires vast amounts of water and arable land; all of which are in short supply. Aquaponics uses a fraction of these resources—as little as ten percent of the land and five percent of the water required in conventional agriculture—without the need for nutrient rich soil. It is a highly sustainable ecosystem in both urban areas where it is marketed commercially and potentially in post conflict areas where resources are unavailable to sustain traditional farming.

Large-scale aquaponics systems rely heavily on technology and Sameh has leveraged low-cost, open-source hardware and software to produce his prototype. Overall, technology helps simplify the process, ensuring maximum efficiency and high-quality production.

(Photo: A picture of the aquaponic facility in the University of Maryland’s agricultural engineering laboratory. Courtesy of Sameh)

With the support of a local governing council in northern Syria and American academics in Maryland, Sameh is developing a prototype of an alternative and sustainable way of farming that could help bring food security to local populations with limited resources and capital.

“We are in the process of building it in the US and are reaching out to universities and researchers to give them the opportunity to join our project. We have to compare it with other aquaponic projects first in order to build a customized prototype.”

Through a personal contact in the Syrian community, Sameh connected with Kurdish representatives in Washington, DC who then connected him to representatives in northern Syria. “I like their way of thinking,” he said. “They were talking about federalism [for Syria] while listening to others,” he continued. After his trip to northern Syria, near the border with Iraq, this year to assess the potential for the project, Sameh came back to the United States in July to conduct research, build a prototype, and seek funding.

Sameh visited University of the District of Columbia (UDC)’s aquaponics system in July through another contact. UDC’s 30 x 80 foot aquaponic system can feed eighteen families with just the vegetables it produces, and can feed up to twenty to twenty-five families with the five-hundred small tilapia fish it raises. This is the size of the prototype Sameh wants to build.

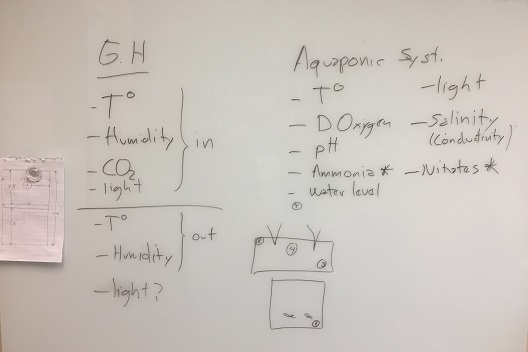

A week later, Sameh met with academics from the University of Maryland and is being allowed to test his prototype automation in partnership with the university. The university is also providing access to a working aquaponic facility and its agricultural engineering laboratory. The University’s aquaponics system uses recyclable equipment, mainly plastics, and shrimp instead of fish.

Building the prototype Sameh has in mind will require identifying the necessary hardware, especially the sensors, and programming, assembling, and testing it at the University of Maryland’s research laboratory. He spoke to an academic about the current challenges he faces and his plans. The professor informed him that the university currently has a project slated for Mexico and offered to let him use the electronics piece on his project as a test in partnership to use data from recyclable equipment. Sameh then plans to test his system on the ground in Syria.

(Photo: Work session on designing the aquaponic prototype with Dr. Izursa at Department of Environmental Science and Technology at the University of Maryland. Courtesy of Flavius Mihaies)

Sameh aims to head back to the region after a year of extensive testing and research, which has taken longer than expected. Despite warnings for him to remain in the United States, as his return could put him at risk of retaliation by the Syrian regime, Sameh is still intent on bringing his prototype to Syria. He is determined to help displaced Syrians without the means to live sustainably, even at risk to himself. At first, Sameh sought to have the project developed in a rebel-held area in southern Syria in 2016, but the arrangement fell through. After showing initial interest, the Syrian opposition group in question abruptly withdrew its support for the project. Sameh persevered and with help from friends, he reached out to a dominant group in the Kurdish territories in northern Syria instead, as the area seemed more stable.

“I am an activist, I follow what’s happening in my country online through news outlets and Facebook. I saw that this area was controlled by one group,” he said, referring to an area maintained by the US-affiliated, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Council. In the US-supported battle against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) in northern Syria, Sameh said the area in which the project will be developed is very protected.

The local council in northern Syria is convinced enough of the project’s potential for food security and job creation to facilitate its implementation. It is hoped that the success of this prototype will ensure that the aquaponic farming system can be reproduced and scaled up in other parts of Syria as well as in other low and middle-income countries.

Sameh said he wants the project to be available and transparent to the community. “I wanted to do something more than protest,” Sameh said, “and show that we, Syrians, can come up with solutions too.”

Flavius Mihaies is a consultant at the World Bank and an independent journalist. He is working on a book about Syria. Follow him on Twitter @flaviousoxford

Image: (Photo: Work session on designing the aquaponic prototype with Dr. Izursa at Department of Environmental Science and Technology at the University of Maryland. Courtesy of Flavius Mihaies)