Odesa Oblast Governor Mikheil Saakashvili is preparing for the launch of his political party later this year in Ukraine, but this has not prevented him from pondering a return to politics in his native Georgia. Georgian voters go to the polls on October 8 to elect a new parliament in a contest viewed as a referendum on the performance of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgia Dream coalition, as well as a barometer of the public’s desire for Saakashvili to return to power.

Odesa Oblast Governor Mikheil Saakashvili is preparing for the launch of his political party later this year in Ukraine, but this has not prevented him from pondering a return to politics in his native Georgia. Georgian voters go to the polls on October 8 to elect a new parliament in a contest viewed as a referendum on the performance of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgia Dream coalition, as well as a barometer of the public’s desire for Saakashvili to return to power.

In the October 2012 parliamentary elections, following eight years of Saakashvili’s rule, Ivanishvili assembled a wide coalition of Saakashvili’s opponents to compete. Due to constitutional changes initiated by Saakashvili, most powers of the presidency had shifted to the prime minister following the 2012 election. This move was designed to allow Saakashvili to skirt the two-term limit for presidents and continue to rule. However, the move backfired and resulted in Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream coalition winning a resounding victory over Saakashvili’s United National Movement (UNM).

The following year, the Georgian Dream candidate for president won an easy victory over Saakashvili’s party’s candidate. However, a weak economy and general disappointment over perceived unfulfilled promises by the Georgian Dream coalition have led to a sharp decline in the ruling party’s popularity since then. In a recent IRI poll, 70 percent of Georgians said the country is headed in the wrong direction. At the same, other polls have put the Georgian Dream party slightly ahead of UNM.

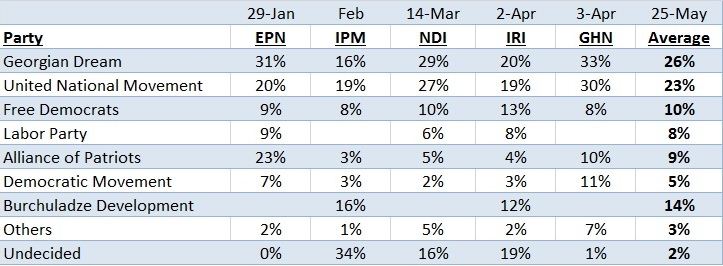

If the elections were held today, what would the new Georgian parliament look like? Of 150 members, seventy-three are selected according to a proportional party list ballot. Any party that receives five percent is awarded seats from the list. Below is a compilation of five recent polls.

According to an average of the polls, Georgian Dream maintains a three point lead over UNM. This has led to speculation of a possible return to power of Saakashvili’s party in the autumn elections. However, this is unlikely for several reasons.

First, UNM is polling at an average of 23 percent, which essentially the same share it received in the October 2013 presidential election. Even when it controlled all of the state administrative resources and most of the media in October 2012, UNM received just 40 percent of the vote, and with nothing having fundamentally changed in the party’s structure, it is hard to envision a scenario where UNM could exceed its 2012 performance.

Conversely, Georgian Dream received 55 percent of the vote as an opposition force in 2012 and is currently averaging 26 percent. Granted, Ivanishvili played an active role and spent freely to oust Saakashvili in 2012. However, while Ivanishvili has moved behind the scenes politically, there is nothing preventing him from again spending heavily to ensure his party’s victory, and Georgian Dream therefore has much more upward potential than UNM.

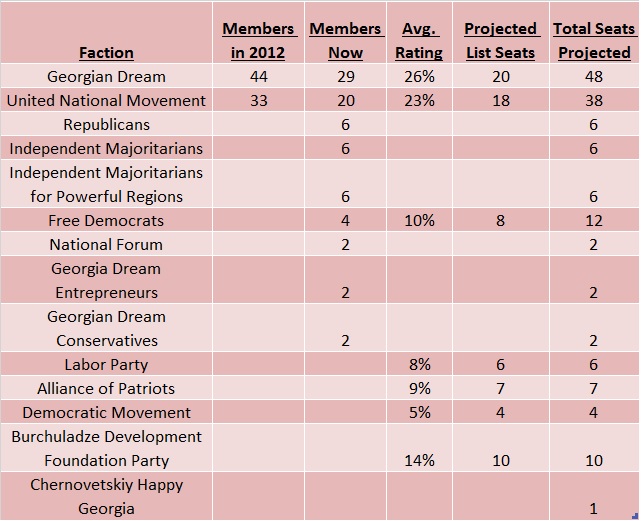

The breakdown of the majoritarian constituencies, which make up seventy-seven of the 150 seats in parliament, do not favor Saakashvili’s return to power. While candidates have not yet been nominated, UNM has failed to win a single parliamentary or other significant post since losing power in 2012. In addition, thirteen of thirty-three majoritarian MPs left the UNM faction following its defeat and joined the ruling Georgian Dream majority.

Even in the unlikely case that UNM candidates defeat the incumbents to reclaim those districts, it would give UNM only fifty-one seats in parliament—far short of the seventy-six needed for a majority. The chart below shows the current breakdown of majoritarian MPs by faction and party.

Another complication for a potential return of Saakashvili to power in Georgia is the rise of smaller parties. The 2012 election was a two-party contest between UNM and Georgian Dream. However, while UNM remains a unitary force, it has lost many MPs and regular members. In addition, Georgian Dream has decided to break the coalition apart and have each party run separately in the parliamentary elections this year.

Some of the important smaller parties include the Free Democrats, who left Georgian Dream prior to this year and are polling an average of 10 percent; opera singer Paata Burchuladze’s Development Foundation Party, which has catapulted into third place; and the Alliance of Patriots of Georgia, a populist and nationalistic movement that emerged from the prison abuse scandal in the 2012 election. However, none of these parties is likely to be a UNM coalition partner.

Other parties with possibilities to win seats in parliament, such as Nino Burjanadze’s Democratic Movement and the Labor Party, openly support Moscow. Thus, there are no easy coalition partners for UNM.

If the polling holds, UNM is likely to remain in the opposition, and Saakashvili is more likely to see his movement prevail in future Ukrainian parliamentary elections than Georgian ones. Either way, the former Georgian president remains a relevant political force in both countries.

Brian Mefford is a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. He is a business and political consultant who is based in Kyiv, Ukraine. This article was shortened from his blog. Follow him on Twitter @meffkiev.

Image: Odesa Governor Mikheil Saakashvili poses with Odesa residents on May 23. Credit: Mikheil Saakashvili Facebook Page