With an eye to the future, officials in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine are waging a campaign of “patriotic education” aimed at reaching the hearts and minds of those most susceptible to ideological persuasion: children.

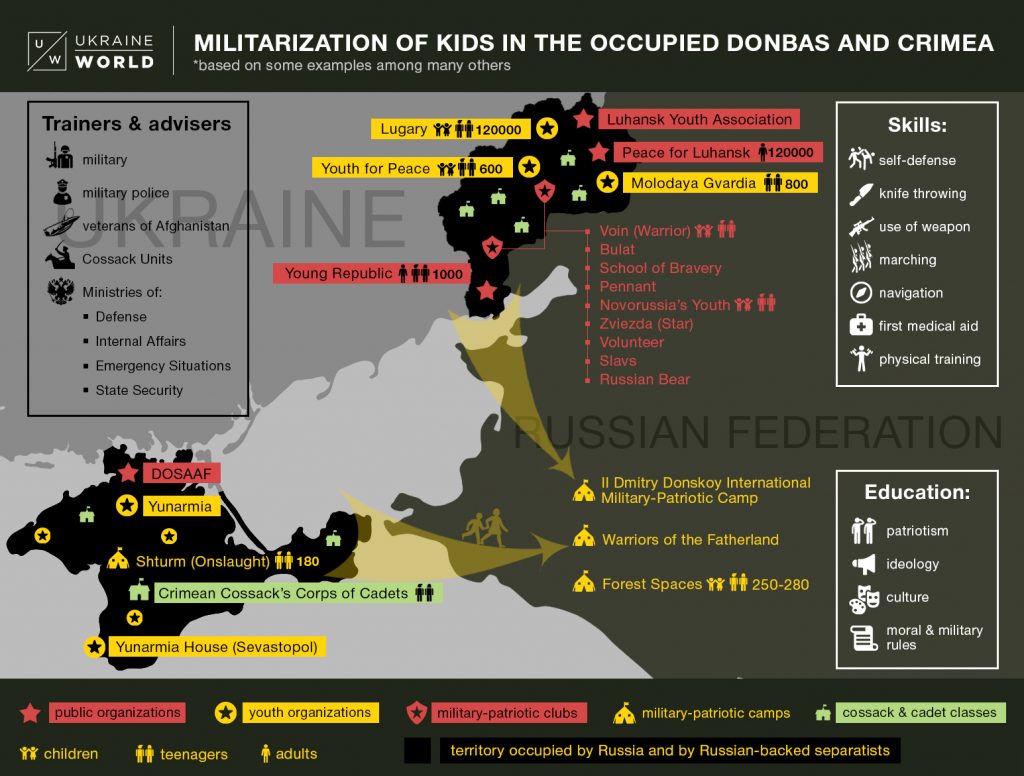

Russia has always used the militarization of public life to indoctrinate local populations and continues that practice today. Currently, thousands of children in the Donbas and Crimea are subject to military training or other military-related activities. While there are no official records on the topic, human rights activists and the media have provided wide-ranging evidence of children’s participation in military-related events and training, and even their recruitment in non-state armed formations.

Military-themed education

Above all, Russia reaches children in the occupied territories of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR), the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), and Crimea through education. The ministries of education in these areas are directly or indirectly supported by Russia and follow the Russian state program on patriotic education, which was approved in 2015.

That year, with its law on “patriotic education,” the LPR compelled educational institutions of all levels, organizations, religious confessions, and even families “to shape children’s consciousness” from an early age. The officials are explicit about their strategic goals: they want young people to “express themselves in strengthening the state and securing its vital interests.”

A similar plan was signed by the self-proclaimed head of the DPR in 2017. That program also includes “pre-conscription training of young people” to encourage them to join the armed forces and participate in the political life of the “republic.” Its core message references the “formation of moral, psychological, and physical readiness of youth to defend the Motherland, loyalty to the constitutional and military debt in peacetime and wartime.”

For school children, “hours of patriotic upbringing” are reportedly common in the republics and Crimea. Schools often host military-related classes and training from public organizations such as the DPR’s Young Republic. Although military-patriotic education is not usually part of the school curricula in annexed Crimea, Iryna Siedova from Crimean Human Rights Group says there is a range of Russian Cossack classes and half-military schools, such as Crimean Cossacks’ Сorps of Cadets for young children there.

Cases of soft but clear militarization in preschools are not rare. A recent video by the DPR’s Ministry of Information shows small kids in military uniforms and caps in the Alenka nursery in Donetsk. The four-year olds repeat exercises after military men, march with DPR flags, sing military songs, and recite patriotic poems. Experts say that militarized classes in preschools are just as common in Crimea.

Other tactics are also used to sway young minds. The Representative of Ukrainian Ombudsman in Donetsk and Luhansk Regions, Pavlo Lysiansky, reported in December 2018 that more than 5,000 children have passed through militarized patriotic camps from the occupied side. Unsurprisingly, such camps often take place in Russia, where they host children from Ukraine’s occupied territories. The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group notes that notorious figures “guilty of war crimes in the Donbas” have contributed to training the children “how to fight and kill.”

Russia also uses military-patriotic clubs to indoctrinate children; as of September 2018, there were forty-eight registered in the DPR. Their official purpose varies between tourist activities and actual military training for youth, but systematic militarization is invariably a priority. Besides regular classes for its cadets, minors are taught military regulations, marching, knife throwing, and dealing with weapons. Cases are regularly reported by the Eastern Human Rights Group on Facebook; recent evidence depicts Luhansk juveniles taking part in shooting exercises as well as disassembling and reassembling machine guns.

Many groups in the occupied regions engaged in this kind of indoctrination emerged on the basis of already-existing NGOs. For example, the first public organization, Peace for Luhansk, was registered in November 2014 and defines its goal as to “fight against fascism, and integration with the Russian Federation.” Notably, more than 13,000 of its members work in education. Some of its projects, such as Care for Veterans, infiltrate youth with ideas of hatred toward Ukraine. Some are overtly aimed at militarization. Another project called Volunteer, launched to engage people in “humanitarian” assistance, reportedly encourages children to go to the frontline.

Although the media also report on training programs in Ukraine’s government-controlled territories, that effort is not as massive as the one occurring in the DPR and LPR and occupied Crimea, according to Justice for Peace in Donbas.

And these programs are still being created. On April 5, a local news website announced the creation of the Yunarmia military-patriotic movement, an analogue of the popular movement in Russia of the same name. It was initiated by Russian Minister of Defense Sergey Shoigu and supported by President Vladimir Putin. Yunarmia is widely known for its robust militarization of children’s life through public activities and events. Last year, Russia-appointed authorities promised that Yunarmia’s clubs would appear “in all schools of Crimea.”

Child soldiers

At the end of June 2018, a video of a child dressed in military uniform shocked social media users. Saying he “helps [DPR fighters] to serve, and assists in shootings,” seven-year-old Nikita adds, “When a Ukrainian appears, we just blast him, and that’s it, he’s f*cked.”

This is not a unique case of a child’s radicalized mindset, and, unfortunately, not just a loud statement. In the occupied regions, Russian propaganda has moved beyond education. Since 2014, children have participated voluntarily in nongovernment armed formations on both sides. However, the number of reported cases in Russian-occupied territories significantly exceeds that on the Ukrainian government-controlled side.

In 2015, Agence France Press published a story about child soldiers “in the making”: twenty kids aged fourteen to nineteen who were trained by Patriotic Donbas in the town of Khartsyzk during their summer break. Reportedly, some of them had already been trained how to use Kalashnikov machine guns. A year later, Justice for Peace in Donbas noted thirty-seven cases of underage individuals who participated in armed formations of so-called D/LPRs, compared to four on the Ukrainian-controlled side.

In fact, minors are reportedly involved in all types of prohibited activities. Russian-backed separatists use children for spying in social media, passing messages, running arms stores, carrying weapons, and serving at checkpoints. It is difficult to track how youngsters get there; however, indicated cases include children who enrolled voluntarily, or were recruited through social media or personal pressure.

International law

The Russian occupying regime and its proxy republics constantly demonstrate their disregard for international law. Since the intervention in Ukraine, Russia has broken its international obligations affirmed in the Geneva Convention and Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict. These prohibit propagandization of voluntary or forced recruitment in state or non-state armed formations on occupied territories—and more so, the recruitment and use of underage individuals in hostilities. By trying to form a positive image of its paramilitary formations and the army, and encouraging children to join their ranks, it also violates Article 29 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which it is a party.

Human rights organizations are continually gathering evidence of such violations in order to hold Russia accountable in the future. According to Siedova, evidence of war crimes is also sent to the International Criminal Court.

With Ukraine lacking access to its occupied territories, the protection of children’s rights in the Donbas and Crimea remains a challenge. At the same time, the country hopes to retake control of the territories eventually. With that in mind, Ukraine must consider now how it plans to reintegrate the younger generations, which are being brought up in an atmosphere of hatred and hostility toward the state they were born in—and which they have been largely isolated from.

Iryna Matviyishyn is a journalist and analyst for Ukraine World Group.

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin talks to children during a visit to the Artek children's holiday camp outside the seaside town of Gurzuf, Crimea June 24, 2017. Sputnik/Alexei Druzhinin/Kremlin via REUTERS