Imagine Winston Churchill saying: “We’ve got to send Nazi Germany a clear signal. At the same time we have to recognize that the Germans do need their lebensraum.” It’s unthinkable.

Imagine Winston Churchill saying: “We’ve got to send Nazi Germany a clear signal. At the same time we have to recognize that the Germans do need their lebensraum.” It’s unthinkable.

But that’s what the West keeps saying to Vladimir Putin’s Russia. The most recent example is United Kingdom Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond telling the BBC: “We’ve got to send a clear signal to Russia that we will not allow them to transgress our red lines. At the same time we have to recognize that the Russians do have a sense of being surrounded and under attack, and we don’t want to make unnecessary provocations.”

Well. We refused Georgia and Ukraine NATO’s Membership Action Plan (MAP) in 2008 so Moscow would not feel “under attack.” We cancelled missile defense in the Czech Republic and Poland 2009 to calm Kremlin fears of “feeling surrounded.” Back in 2002, we established a NATO-Russia Council, designed so that Russia and Alliance members could “work as equal partners on a wide spectrum of security issues of common interest.”

What did this get us?

Ukraine is at war, Georgian territory is occupied, the Baltic nations are feeling threatened, the Visegrad nations are wobbly and divided, and NATO’s southern flank is in disarray.

It’s time we realize that western weakness is provocative. It’s also time for a reset in our approach to the continent. This means that we set an agenda that advances our interests and values—rather than merely reacting to an agenda set by Putin.

What would that look like?

First, let’s affirm our vision of a “Europe whole and free.” That’s the phrase used by President George H.W. Bush in a May 31, 1989, speech in Mainz, West Germany. Within two weeks, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev signaled that the Soviet Union would not interfere with the liberalization underway in Eastern Europe. Within five months, the Berlin Wall was open. So Putin has broken with the course set by Gorbachev, and followed by his successor Boris Yeltsin. Does this mean we break with ours?

Second, let’s develop a revitalized NATO strategy. Aspirant countries need new forms of association and fresh perspective for Euro-Atlantic integration. The MAP process—which includes a range of political and technical advice—is still important. It can be augmented, though, by military training and assistance in enhancing intelligence and surveillance capabilities on a country-by-country basis. And just as we established a NATO-Russia Council, let’s create a NATO Council for Nations in Democratic Transition to expand dialogue on opportunities and obstacles to deepening Euro-Atlantic integration. We risk losing the aspirants. In Georgia, one recent poll indicates growing support—31 percent up from 16 percent a year ago—for joining Putin’s pet project, the Eurasian Economic Union. In Moldova, barely a third of the country, according to one recent survey, support joining the EU. As the EU’s doors are likely to remain closed to any new members for the foreseeable future—concerns about Greek and UK exits being all consuming for Brussels and national capitals—it’s important that NATO keep enlargement on track.

For those who wish to join and qualify—Macedonia and Montenegro should top the list—NATO enlargement must remain a real possibility. Montenegro was invited to join MAP in 2009, and Macedonia has met the same qualifications. Both countries can help to anchor NATO’s southern flank and keep the Russians at bay. In 2013, Montenegro rejected a Russian request to install a military base in its Adriatic port of Bar. Let’s help to shield these small nations from Russian pressure and intimidation and keep them moving westward.

Meanwhile, existing NATO members need reassurance and reinforcement. The United States is now considering the stationing of tanks and other heavy weaponry and maintaining a force of up to 5,000 US troops in the Baltic States, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, and possibly Hungary. That’s a move in the right direction. Such steps need to be matched, though, by considerable diplomatic effort to restore political cohesion and a sense of purpose in the Alliance. When the Prime Minister of Hungary, to cite one prominent example, sympathizes with Putin over Ukraine and lauds authoritarian capitalism as practiced in Russia and China, we know Alliance drift has gone too far.

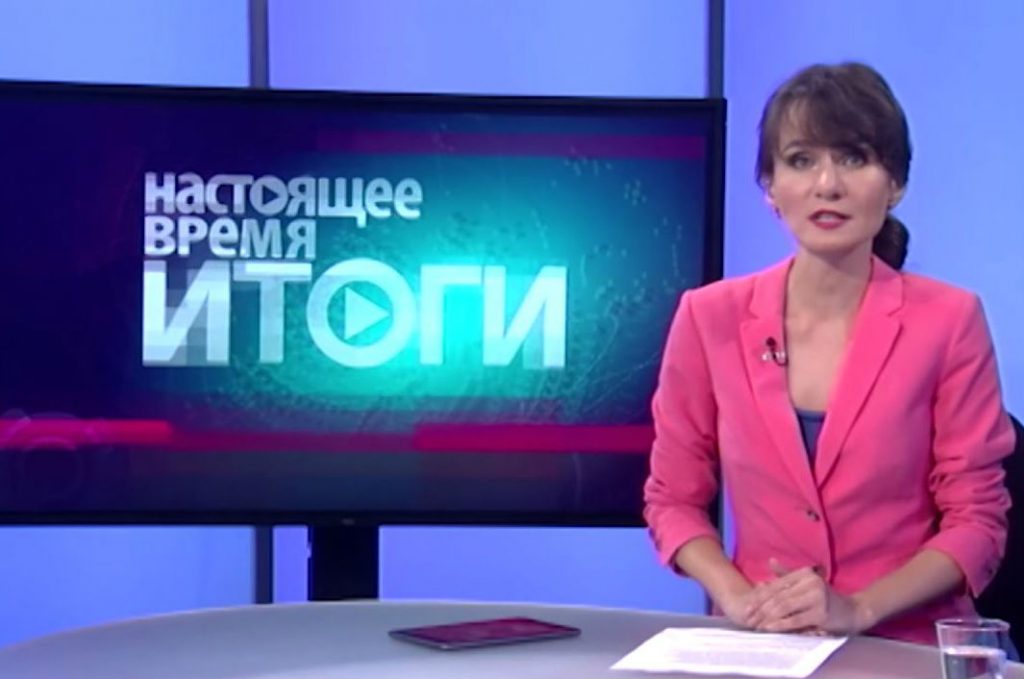

Third, let’s develop information and media strategies worth their name. It’s astonishing how Congress and the Obama administration have dithered over the reform of US international broadcasting. There’s a bill co-sponsored by Ed Royce (R-CA) and Eliot Engel (D-NY) that deserves speedy passage in the House and the Senate and approval by the President. This will give the Voice of America and a newly consolidated Freedom News Network—merging Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Radio Free Asia, and the Middle East Broadcast Network—the chance to operate more efficiently and effectively. It’s time to resource properly television capabilities. How woefully and embarrassingly inadequate it is that VOA and RFE/RL now have funding to produce a new Russian language television show for a meager thirty minutes a day. As for content, let’s worry less about trying to respond to Putin’s disinformation. It’s not unimportant to play defense. But we need to be far more assertive about defining our own agenda, and Radio Liberty has already started on this track. The Russian people must hear about what Putin is doing to their country. That means accurate news and information in Russian to Russia about the impact of Putin’s policies. No Russian patriot wants to see Russia’s future destroyed by self-serving deception and costly foreign adventures.

Fourth, make Putin pay for his adventures. Start by driving up the cost for his intervention in Ukraine. Sanctions are necessary, but not sufficient. Ukrainians need arms and training to fight for their country. Don’t allow Putin this cake-walk.

We behave as if the Russian President is unbeatable. He’s not. Let’s end the parlor game of puzzling what “he” is up to do next. Let’s advance our own agenda. It’s time we give Putin something to think about.

Jeffrey Gedmin is senior fellow at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, senior advisor at Blue Star Strategies, and co-director of the Transatlantic Renewal Project.

Image: Yulia Savchenko, is the host of “Current Time,” a joint production of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and the Voice of America. Giving Putin something to think about means developing information and media strategies worth their name. It's time to resource properly television capabilities. Credit: 24 Канал