Experts anticipate a new cyberattack on Ukraine’s critical infrastructure this month; they have observed increased activity from the same hackers involved in a previous cyberattack. In the last two years, cyberattacks on Ukraine’s power grid coincided with the winter holidays, a sensitive time with a high demand for critical infrastructure. A cyberattack may target civilians to sow popular discontent with the state’s inability to stave off these disruptive attacks.

Experts anticipate a new cyberattack on Ukraine’s critical infrastructure this month; they have observed increased activity from the same hackers involved in a previous cyberattack. In the last two years, cyberattacks on Ukraine’s power grid coincided with the winter holidays, a sensitive time with a high demand for critical infrastructure. A cyberattack may target civilians to sow popular discontent with the state’s inability to stave off these disruptive attacks.

Since 2014, the country has experienced far more cyberattacks than in the past, and they have grown more sophisticated. In fact, experts consider Ukraine a “testing ground” for hackers to perfect their capabilities and tactics. Often, their digital fingerprints and motives imply Russian involvement.

Ukraine has taken steps to develop its national cybersecurity system; it has updated its legal framework with a law on cybersecurity fundamentals and a cybersecurity strategy, set up government cyber units, created a cybersecurity coordination center, and banned Russian software. However, Ukraine still has no comprehensive cybersecurity system. The country is not keeping up with the pace of constantly-evolving cyberattacks and has only been reacting to cyber threats. Leading experts agree that Ukraine’s interagency coordination is feeble, and its public-private partnerships are underdeveloped.

The government admits that low pay and a lack of modern technology contribute to its shortage of skilled workers. And the overall level of cybersecurity literacy among Ukrainians is low.

Due to years of negligence and financial strain, many offices still run on old IT equipment, use unlicensed software without critical updates (including Windows XP), and improperly store confidential documents. These malpractices create vulnerabilities and make things easy for hackers. Ukrainian companies are finding out that antivirus software and firewalls alone are inadequate against targeted attacks. Given these hurdles, Ukraine is more engaged in costly mitigation than in prevention.

In addition, lessons aren’t being learned. Employees are constantly reminded to disable unnecessary network protocols; to not log into the operating system with an administrator’s account; and to not open attachments even from reliable sources without confirmation from the sender by phone or text message. But this doesn’t seem to be getting through.

The ransomware attacks this year underscored the vulnerability of Ukraine’s IT systems and the lack of cybersecurity practices in government and the private sector.

After the WannaCry cyberattack in May, many Ukrainian companies ignored recommendations to protect their systems with patches and educate staff to avoid phishing emails. This facilitated the NotPetya ransomware cyberattack in June, which went down as the largest cyberattack in Ukraine’s history. Thirty minutes after NotPetya was unleashed, the economy lost 0.4 percent of GDP (about $36 million) in revenue. Later it was discovered that NotPetya wasn’t a genuine ransomware attack but rather a wiper used to hide the tracks of large-scale theft of corporate data. But even after NotPetya, only 10 percent of public and private companies are adopting strong cybersecurity practices.

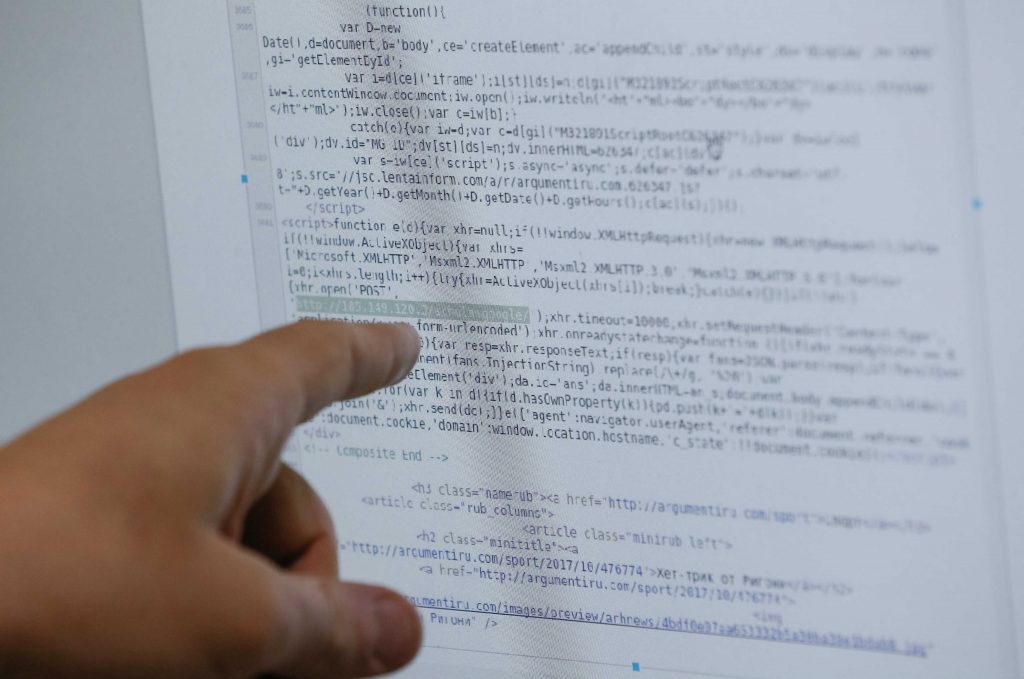

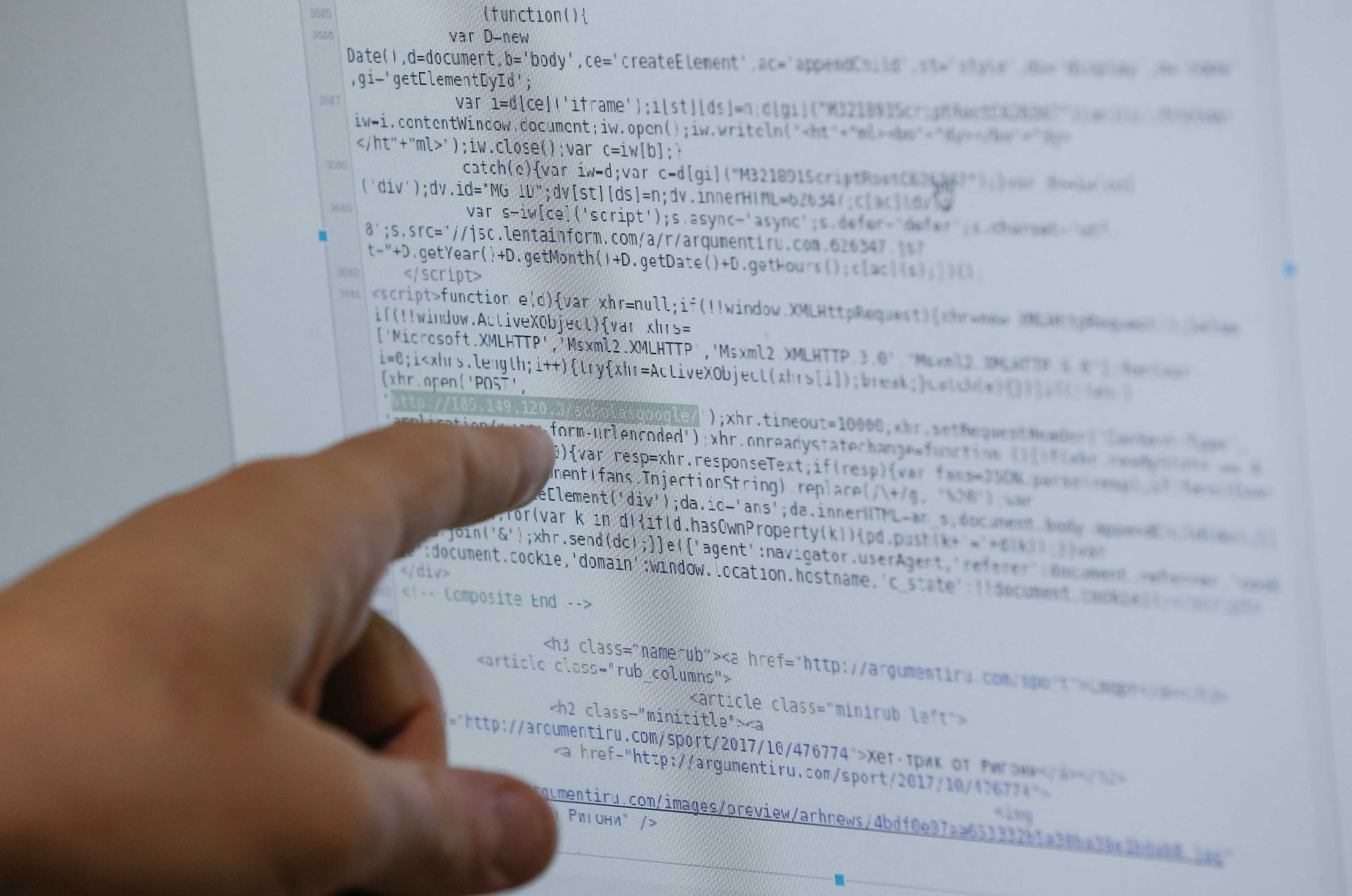

NotPetya was followed by yet another, though less damaging, cyberattack named Bad Rabbit, believed to be a modified version of NotPetya. This attack hit public transportation in Ukraine by targeting particular employees to trick them to install a virus. Although the attack mostly affected media in Russia, Ukraine’s cyber police believe that it was a decoy to hide the real target: Ukraine.

European intelligence attributed NotPetya to the Kremlin, and Ukraine’s cyber police said that some Russian-sponsored hackers were among the perpetrators. Igor Kozachenko, CEO of the cybersecurity firm ROMAD, believes that Russian intelligence used NotPetya to measure how quickly Ukrainians would thwart an attack. He also thinks that NotPetya was a cyber weapon aimed to discredit the security reputation of Ukraine’s information systems.

So what else is being done? Realizing the importance of international cooperation in repelling cyber threats, Ukraine is collaborating with the United States, NATO, and the European Union. It’s willing to share its valuable frontline experience, which the West can use to improve its own capabilities. The West is apprehensive that Russia may use these honed tactics on the West’s networks. Hence, Western governments and organizations are providing financial assistance and new equipment, and are holding joint exercises with Ukraine to boost its capability.

While the government is mobilizing its efforts, the country has been developing a bottom-up approach to cybersecurity, known as “cyber resilience.” The private sector helps the government put out fires and restore critical data. Volunteers, such as Inform Napalm and Ukrainian Cyber Alliance, also assist security agencies with information gathering. But the work of patriotic hackers isn’t always appreciated when they detect embarrassing holes in government websites or find public access to confidential information.

Experts agree that Ukraine needs a systematic approach to its cybersecurity based on strong cooperation between the public and private sectors. Until more industry-specific response teams and information sharing centers are set up with regularly trained staff, and the level of basic cybersecurity awareness among citizens improves, all the political statements about improving national cybersecurity will remain simply declarative.

Vera Zimmerman, a UkraineAlert contributor, is an independent research analyst and translator.

Image: An employee shows, what he said is a part of malicious script used during a Bad Rabbit virus attack, on a computer screen at the Ukrainian Cyber Police headquarters in Kyiv, Ukraine November 2, 2017. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko