The need for reconciliation between eastern and western Ukraine is often emphasized in Ukrainian and international media, and has been the subject of dozens of roundtables in the past couple of years. Though originally from western Ukraine, I have lived and worked in the east for nearly two years, and I have come to realize that the approach and terminology currently in vogue are wrong.

The need for reconciliation between eastern and western Ukraine is often emphasized in Ukrainian and international media, and has been the subject of dozens of roundtables in the past couple of years. Though originally from western Ukraine, I have lived and worked in the east for nearly two years, and I have come to realize that the approach and terminology currently in vogue are wrong.

If we use the term “reconciliation,” we automatically subordinate ourselves to Russian propaganda and agree that there has been a genuine internal conflict between Ukrainians. In fact, the conflict has been artificial. If we gather at “reconciliation” roundtables, we automatically perceive our interlocutors as enemies. It creates a negative and destructive base for dialogue.

We have not fought with each other; therefore, we do not need to reconcile. The real problem is that we have never actually spoken to and do not really know each other. Most of the communication between the two sides has been conducted through oligarch-owned media and rumors based on stereotypes. In fact, what we need is communication, not reconciliation. As prominent historian and co-founder of the Nestor Group Yaroslav Hrytsak has put it, “If there is no communication, there can be no nation.”

Thus, for the past three years, the Lviv Education Foundation (LEF) has been at the forefront of this fight, training citizens in an essential component of Ukrainian nation-building.

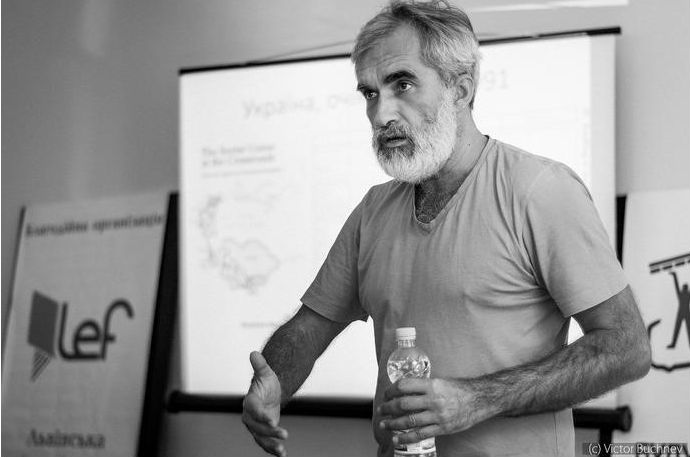

Ukrainian historian and public intellectual Yaroslav Hrytsak speaking to volunteers about the importance of their generation at the Responsibility LAB in the Carpathian Mountains, October 2016. (Credit: Victor Buchnev)

In July 2014, a few weeks after Ukrainian soldiers liberated Kramatorsk, LEF’s director Vitaliy Kokor organized a field trip to the postwar town to figure out how we could help. Weeks later, LEF set up a volunteer camp there composed of more than eighty volunteers from western and central Ukraine who helped locals rebuild homes. Thousands of hryvnias were raised through a crowd-sourcing platform and more than thirty houses and apartments were renovated free of charge.

Rebuilding in Kramatorsk.

For most locals, it was their first time communicating with Ukrainians from regions other than Donetsk. They were impressed and touched to see that students, IT specialists, journalists, and others from one thousand miles away came to help restore their city. For some, it was the first time they had thought of Kramatorsk as part of a country and felt national pride for their co-citizens.

The camp was unique: in the morning, volunteers performed hard physical labor; in the evening, they’d gather at a bonfire and chat with locals.

LEF tried to create a non-imposing atmosphere for dialogue: it is much more fruitful to talk about complex issues while carrying bricks and plastering walls than while sitting at a table and following an agenda.

While in Kramatorsk, the volunteers rented a house with a garden in the suburbs and invited local young people to join them for bonfires, movie screenings, and evening discussions. This improvised youth hub attracted dozens of teenagers from Kramatorsk and the neighboring city of Slovyansk. Since those towns lacked a cultural center where young people could gather, Kramatorsk camp coordinator Mykola Dorokhov decided to create a permanent youth center called Vilna Khata, or Freedom Home. This week, it celebrates two years in operation.

Freedom Home in Kramatorsk.

Since its opening, more than twenty thousand people have visited the center, an informal place where eastern Ukraine meets western Ukraine. Anyone can read, have a cup of coffee, play the guitar, or enjoy a board game.

Since 2014, Freedom Home has inspired dozens of visitors from other regions, resulting in the creation of twelve more youth hubs throughout Ukraine (in Pokrovsk, Bakhmut, Novohrodivka, Kostiatynivka, Mariupol, Slovyansk, Druzhkivka, Pavlohrad, Chervonohrad, Vinnytsia, and Enerhodar).

Those youth hubs serve as cultural bridges between regions of Ukraine and the rest of the world. The centers host famous cultural and public figures to connect young people with larger intellectual and cultural trends. Recent guests have included leading Ukrainian poet Sergii Zhadan, singer Oleksandr Polozhynskyi, former Minister of Economic Development Pavlo Sheremeta, and public intellectual Yaroslav Hrytsak.

Realizing that volunteerism is ideal for mobilizing local communities and fostering communication between regions, LEF scaled up its programs this year and held seventeen weeks of service camps in eleven towns in eastern, central, and western Ukraine.

Over the summer, more than 400 volunteers from Ukraine, Russia, and the United States joined the Building Ukraine Together effort. Over forty houses and apartments belonging to war veterans and families were rebuilt. In addition to providing assistance to families, volunteers conducted public activities to attract more local youth and spread the idea of personal responsibility. We renovated and constructed public spaces, painted thought-provoking graffiti, and cleaned streets.

The main goal was to show volunteers that small service acts actually make a difference, that cleaning a river or painting a wall affects the world around us.

Volunteers from the Building Ukraine Together initiative.

The project’s strength comes from the fact that most of the service camp’s participants have zero experience in civic activism. After one or two weeks, they go through an intensive training in responsible citizenship and then return to their towns with ideas, teams, and project implementation plans. LEF uses volunteer activities as an educational tool to teach young people responsibility, practical action, and teamwork.

This year, the most active volunteers who had their own ideas of how to transform their villages, towns, and country joined LEF at a week-long educational program called Responsibility LAB that was held in the Carpathian Mountains at the end of the summer.

A sense of responsibility is a feature most Ukrainians lack—and that is exactly what we are trying to teach ourselves. It’s easier to find a leader and faithfully follow him than it is to create a movement and lead people ourselves. It’s easier to work for someone else’s business than to take a risk and start one’s own. It’s easier to vote and pass responsibility for the country onto someone else than it is to take responsibility and rebuild it ourselves.

The Building Ukraine Together project forces us to leave this paradigm behind. It changes the world where we demand changes, and builds the world in those places where we make changes ourselves.

Yuriy Didula, a UkraineAlert contributor, is a project manager at the Lviv Education Foundation.

Image: More than 400 volunteers from Ukraine, Russia, and the United States joined the Building Ukraine Together effort during the summer of 2016. Pictured here are some of its volunteers. Credit: Lviv Education Foundation