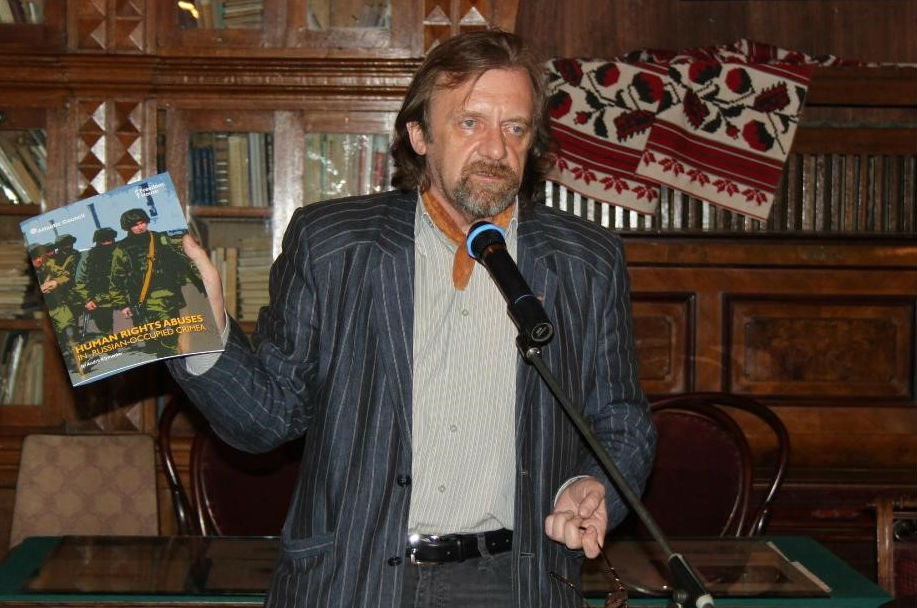

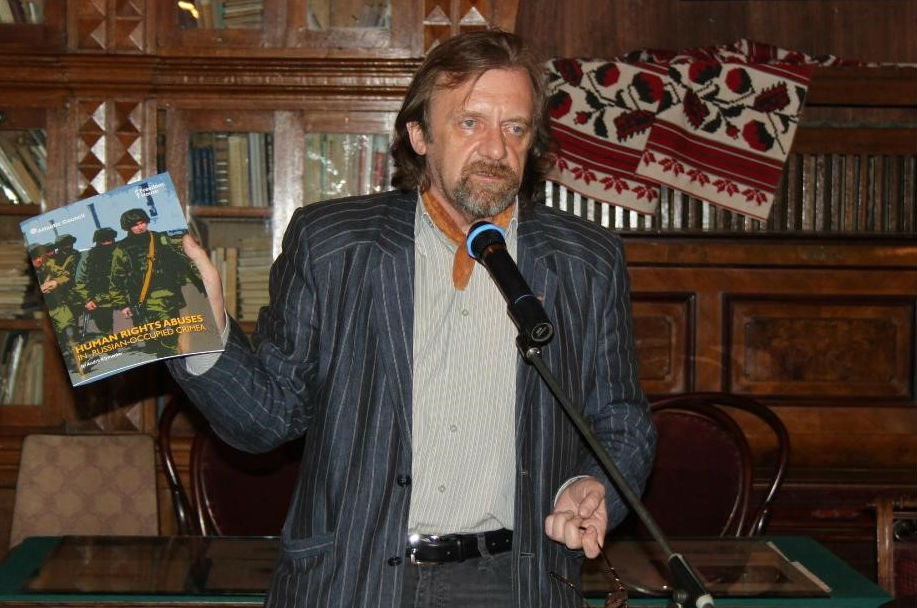

In March 2015, the Atlantic Council and Freedom House published a report by Crimean journalist Andrii Klymenko showing how Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea has unleashed an ongoing chain of human rights violations across the peninsula.

In March 2015, the Atlantic Council and Freedom House published a report by Crimean journalist Andrii Klymenko showing how Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea has unleashed an ongoing chain of human rights violations across the peninsula.

Five days after release of the report—Human Rights Abuses in Russian-Occupied Crimea—Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) charged Klymenko with challenging the annexation’s legitimacy and threatening Russian sovereignty. Under Article 280 of Russia’s criminal code, Klymenko faces up to five years in jail. Yet Klymenko wasn’t told about the charges; he learned about them in April, when the FSB began searching and interrogating his former colleagues.

As a result, Klymenko cannot visit Crimea, where his parents are buried. Nor can he enter Russia or any territory the Russian Federation controls without risking immediate arrest. Klymenko assumes he’s also been blacklisted by the three member states of the Eurasian Economic Union: Armenia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan.

Klymenko is co-founder and editor-in-chief of the online Black Sea News, established in September 2010. Black Sea News has received support from the US Agency for International Development and the Internews Network.

During Russia’s occupation of Crimea, Klymenko worked in a safe house after having he’d been alerted that his work had caught the FSB’s attention and that he was a person of interest.

Klymenko knew that Crimea would enact Article 280 in May 2014, so he preemptively moved to Kyiv with his family in April 2014—the month after Crimea’s annexation—to avoid prosecution. Other Black Sea News staffers have relocated as well to Kyiv, Kherson, and other cities in Ukraine.

But Klymenko and his team understand Crimea’s political and economic situation, and their contact with journalists, politicians, and residents who travel back and forth between Kyiv and Crimea enables them to “read between the lines, to compare, to separate truth from falsehood.” That’s what makes them dangerous to the new authorities in Crimea.

Even though its staff has fled to mainland Ukraine, Black Sea News carries on. Klymenko’s reporters get news from Crimean and Russian sites, and they scour social networks as well. Since annexation, the Russian Federation has cracked down harshly on journalists and civil society.

Sadly, Klymenko’s story isn’t unusual for independent-minded journalists. In March 2015, the FSB searched the Simferopol residence of Natalia Kokorina, editor of the Center of Journalistic Investigation, and raided her parents’ apartment. In early 2014, authorities expelled journalist Sergei Mokrushin from the Crimean city of Kerch; they also harassed the parents of Anna Andrievskaia, a Simferopol journalist. Like Klymenko, Andrievskaia, who writes for Crimea.Realities, relocated to Kyiv because she faces up to five years in prison—also under Article 208 of Russia’s Criminal Code—for her report on a Crimean volunteer battalion.

Klymenko said he doesn’t trust Crimean media. All Internet providers cooperate with the FSB; they must also store information on every user’s Internet activity and hand it over to the FSB immediately, and without even a court order.

“There’s no independent media in Crimea, or foreign journalists either,” wrote Klymenko in a July 30 interview, noting how hard it is to do real journalism there today when one cannot even set foot there. “In order to understand what’s really happening in Crimea, you have to work hard. You have to know the newsmakers in Crimea well and understand them personally. You have to make use of every crumb of information, no matter how trivial, and then you have to analyze it, double-check it. That’s how you put the puzzle together.”

Klymenko hasn’t sought assistance from Western embassies in Kyiv and has no plans to do so, though he does want to share information with them. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s economic crisis and ongoing hostilities in eastern Ukraine have pushed Crimea out of the world’s headlines—an irony, said Klymenko, because Crimea’s status is more important than that of the Donbas.

“If the world forgets about the annexation of the Crimea, Putin will go further,” Klymenko warned, noting that Russia’s takeover of Crimea marked Europe’s first annexation since World War II.

He readily admits that it’s difficult for foreigners to comprehend how Russia could expropriate state and private property, and force Russian citizenship on all Crimean residents.

“People in the West, know that citizenship is a very complex legal institution, so they just can’t understand this. They think in terms of international law and human rights,” he said, adding that Russia operates “outside of international law and human rights.”

Melinda Haring is editor of UkraineAlert at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Five days after release of Crimean journalist Andrii Klymenko’s report in March 2015— Human Rights Abuses in Russian-Occupied Crimea—Russia’s Federal Security Service charged him with challenging the annexation’s legitimacy and threatening Russian sovereignty. Under Article 280 of Russia’s criminal code, Klymenko faces up to five years in jail. Credit: Courtesy photo