In the last three decades, Ukraine has experienced three dramatic changes that have often been referred to as revolutions. But were they genuinely revolutionary?

In the last three decades, Ukraine has experienced three dramatic changes that have often been referred to as revolutions. But were they genuinely revolutionary?

In October 1990, as the Soviet Union was decaying, Ukrainian students, dissatisfied with the communist majority in the parliament after the 1990 elections, took to the central square of Kyiv. The protests resulted in the resignation of the head of the government and were one of the important elements that led to the collapse of the Soviet regime.

However, they failed to bring radical change. The early decades of post-communist Ukraine were marked by the dominance of ex-communist nomenclatura and new criminal leaders who earned their wealth through dirty tricks, mostly by privatizing and re-distributing formerly state-owned assets.

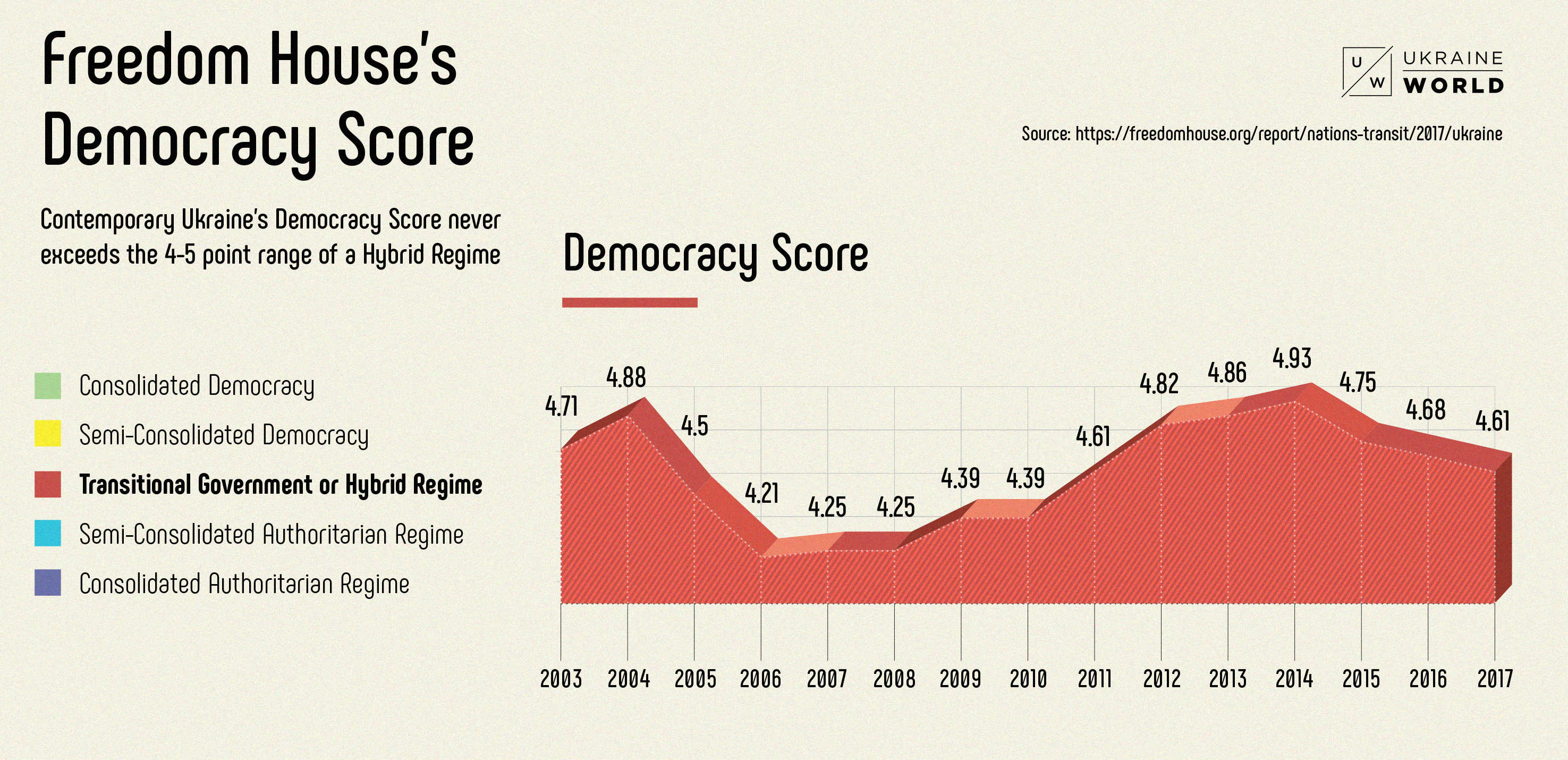

“While the first ‘revolution’ in 1990 precipitated a decline in late Soviet totalitarianism, it was not enough to push Ukraine onto the liberal reforms track,” said Yuriy Matsiyevsky, head of the Center for Political Research at Ostroh Academy National University. “By the end of the first term of Leonid Kuchma’s presidency in 1999, Ukraine had descended into a hybrid regime that combined competitive elections with corruption, cronyism, and nepotism. This still persists today.”

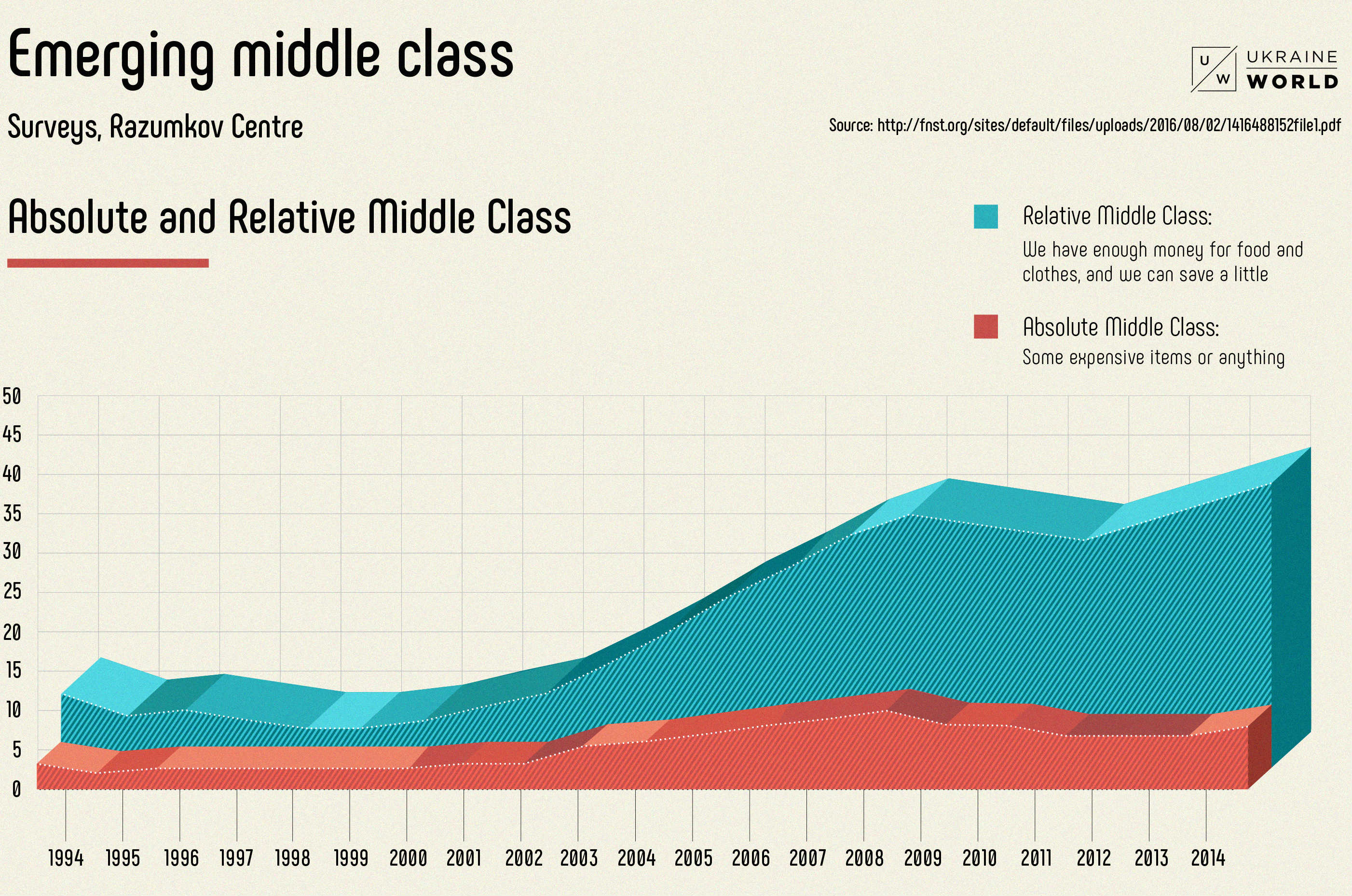

The 2004 Orange Revolution was a reaction to this post-communist kleptocratic and semi-criminal government. People took to the streets to protest against rigged presidential elections. They were hoping that opposition leaders would be able to change the regime. The driving force was the middle class, which had begun to emerge in the 2000s and demand political rights. “Young educated people whose basic needs have been satisfied and who represent values of self-expression are prone to protest,” said Yaroslav Hrytsak, a Ukrainian historian and professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University.

Those mass protests managed to reverse the rigged results of the presidential election and bring opposition leaders Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko to power. However, the main problem of the Orange Revolution was an extension of its key hope. The people believed too much in their leaders: their messianic ability to change the country and their moral integrity. This was a mistake. The new government failed to conduct true reforms; oligarchs and vested interests continued to control politics.

Ten years later, the Euromaidan protests, also known as the Revolution of Dignity, resembled a “real” political revolution, and was the most radical of the three. It was a bottom-up movement. People of various social classes took to the streets. There were many middle-class representatives, but also students, pensioners, and factory workers. Such a broad coalition that genuinely represented society made it stronger and more united.

The events on the Maidan spread beyond the capital. Some regional authorities refused to obey the central government after several attempts by the government of then-president Viktor Yanukovych to brutally disperse Maidan protesters. This had not happened during the previous two revolutions.

Instead of having blind faith in leaders, the Euromaidan attempted to bring people from civil society and the expert community into government. It succeeded in part. But again, it lacked a revolutionary outcome—a change of regime—admits Matsiyevsky.

Nonetheless, its achievements are the greatest of the three revolutions.

First, new actors entered Ukrainian politics. They don’t belong to the old clique and yearn for a democratic breakthrough. But their influence is still not sufficient to break the system. There need to be more of them in order to bring real change.

Second, violence during the confrontations in 2013-14 unified the Ukrainian people as a nation. “Each revolution triggered stronger patriotic feelings and a stronger desire for freedom,” says Oles Doniy, a leader of the 1990 protests and a participant in all three.

Society is clearly thirsty for democracy. The protests were not for food or money but for values and human rights. People took to the streets for the sake of dignity. According to Hrytsak, these repeated protests were partially the result of a national memory and identity based on Cossacks—Ukrainian warriors who were active in the 16th-18th centuries—and self-governing society at the time.

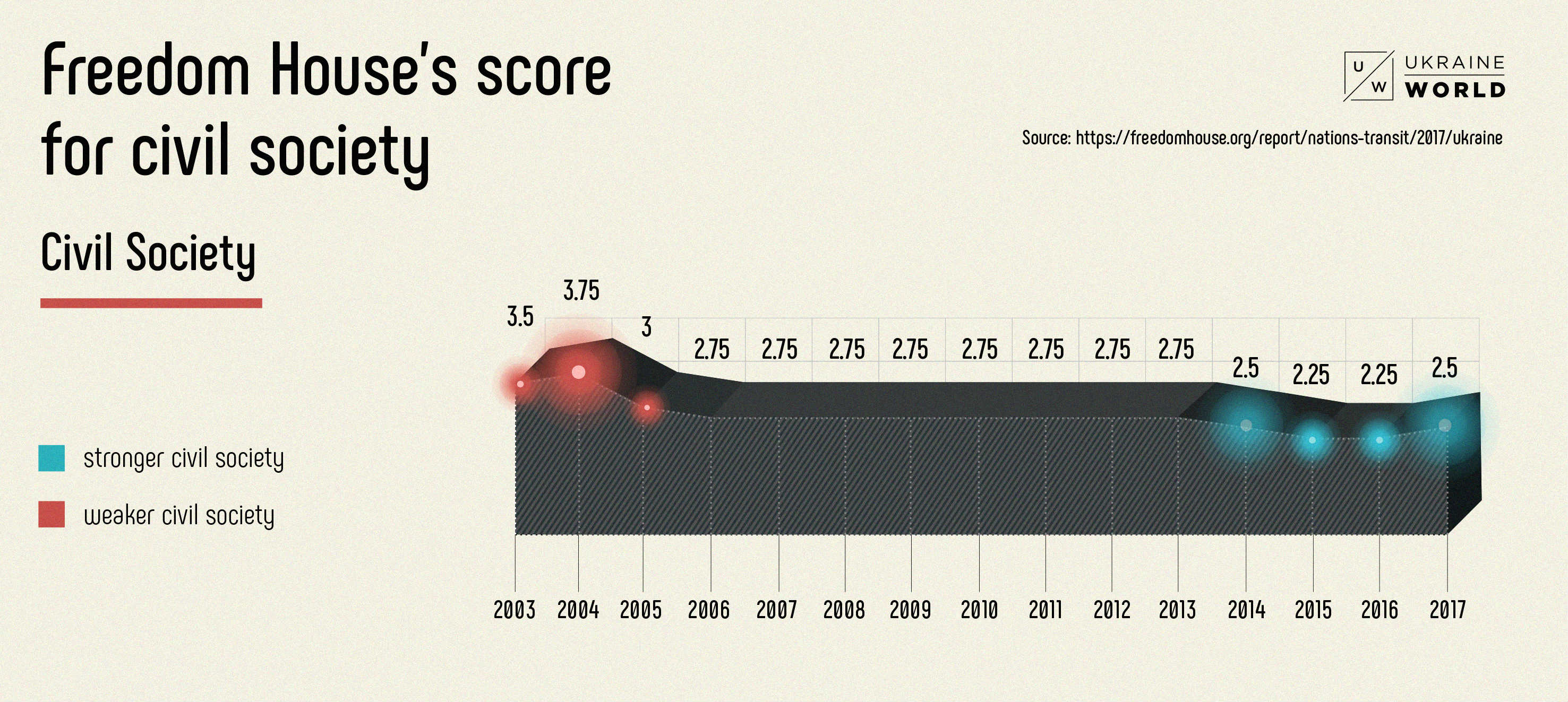

Whatever the reason, the revolutions bore fruit. After each one, the country became more democratic, further enhancing civil society. Now it has more weight in pressing for reforms, primarily in the fight against corruption.

But this is not enough. Since the 2000s, Ukraine’s democratic score, according to Freedom House, has been consistently within the four- or five-point range that corresponds to partly-free hybrid regimes.

In order to shift this for good, more new actors are needed in Ukrainian politics who want to change the typical way of doing business.

“In order for a more democratic regime to emerge, two conditions must be satisfied: first, new players should enter the political stage and, second, these new players should accept the new rules of the game,” says Matsiyevsky.

Doniy emphasizes the importance of values; he argues that ‘”single heroic outbursts cannot change the system. The latter requires a new system of values, European values, and state structures built on the basis of these values.”

Revolutions rarely succeed. But they can raise people’s consciousness and shake state structures. They can launch desired changes. They can be important social and political outbursts that trigger new developments.

In short, so-called “revolutions” can be crucial tipping points in a long-term evolution, which is a force that really brings change. Ukrainian revolutions seem to be those tipping points, but the real evolution is yet to come.

Ruslan Minich is an analyst at Internews Ukraine and at UkraineWorld, an information and networking initiative.

Image: A member of the "Maidan" self-defense battalion listens to speeches at the site of recent street battles near Independence Square in Kyiv March 1, 2014. REUTERS/Thomas Peter