With Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk’s government surviving a no-confidence vote on February 16 and the parliamentary coalition splintering the next day, early parliamentary elections are now possible this year. New elections could be triggered by three scenarios: first, if the current majority coalition in parliament collapses and a new majority isn’t formed within thirty days; second, if Yatsenyuk resigns early, or is dismissed in the next session of parliament (which starts in late August), and parliament can’t agree on a replacement; or third, if parliament votes no confidence in the prime minister. In all cases, the President has the right (though not the obligation) to dismiss parliament and call new elections.

With Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk’s government surviving a no-confidence vote on February 16 and the parliamentary coalition splintering the next day, early parliamentary elections are now possible this year. New elections could be triggered by three scenarios: first, if the current majority coalition in parliament collapses and a new majority isn’t formed within thirty days; second, if Yatsenyuk resigns early, or is dismissed in the next session of parliament (which starts in late August), and parliament can’t agree on a replacement; or third, if parliament votes no confidence in the prime minister. In all cases, the President has the right (though not the obligation) to dismiss parliament and call new elections.

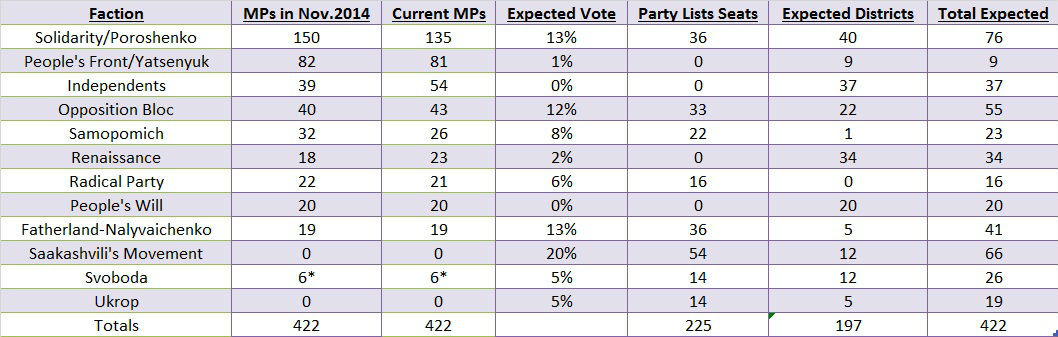

Below is a prediction of how each of Ukraine’s major parties would do if elections were held now. This model makes four assumptions. First, the current system of electing half of Ukraine’s MPs by district and half by party list remains. Second, ratings are based on recent polling data (gathered by the International Republican Institute and the Democratic Initiatives Foundation) and historical trends. Third, the twelve districts in Crimea and Sevastopol, as well as the occupied sixteen districts in the Donbas, will not participate in the elections. Fourth, MPs from the People’s Will faction will be reelected.

Solidarity/Poroshenko: The President’s popularity was around 40 percent when his party received 22 percent of the vote in the October 2014 parliamentary elections. His popularity is now half of that, and his party is currently polling around 10 percent. However, Solidarity could perform well in the sixty-eight districts that the party won in 2014. With some administrative resources, Solidarity could receive about 13 percent of the proportional ballot. These factors would give Solidarity fewer than eighty deputies (versus one hundred fifty in 2014) but would still leave them as the largest faction.

People’s Front/Yatsenyuk: The premier’s party emerged from nowhere and finished first in the October 2014 elections. However, his rating has since disintegrated, and his party’s rating with him. With the People’s Front unable to get 5 percent of the vote, and only eighteen MPs from districts, faction members are searching for options. At best, half of the People’s Front MPs from districts would win reelection. That would represent a sharp decline from eighty-two seats to nine.

Samopomich: This party won the reform vote with an impressive 11 percent in 2014 and thirty-two MPs. Polls put them at around 8 percent, which is adequate to return to parliament, but represents a slight decline. This support may return, but given the competition from Oblast Governor Mikheil Saakashvili’s reform movement, it is likely that Samopomich will struggle to keep its rating. Therefore, with new elections, Samopomich could decline from thirty-two MPs to approximately twenty-four.

Fatherland/Tymoshenko with Nalyvaichenko: Once enemies, former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko and former SBU chief Valentyn Nalyvaichenko have recently allied. Current polling puts Fatherland at around 8 percent, but the addition of Nalyvaichenko will increase its support in the West and in Kyiv. The union is untainted by the unpopularity of the current government and is positioned to benefit. Tymoshenko received 13 percent of the vote against Poroshenko in the May 2014 elections, and it’s possible she can equal that again. With new elections, Tymoshenko-Nalyvaichenko could expect to double their deputies in parliament to more than forty.

Saakashvili’s Reform Movement: Saakashvili’s reform movement is gaining momentum, but is not yet an actual political party. Eventually, though, a new party will be formed, which will make an ideal coalition partner for the President’s Solidarity Party. There is no polling data for this movement; however, Saakashvili’s popularity is close to 40 percent. While there are still many uncertainties, it is possible that the movement could win a dozen individual districts, in addition to its first-place proportional ballot performance. Thus, with new elections, the “Misha Movement” could have roughly seventy MPs.

Ukrop/Renaissance/Kolomoyskyi: The oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyi maintains the patriotic Ukrop Party for voters in the west, and the pragmatic Renaissance Party for voters in the east. At the moment, Ukrop polls close to 4 percent, but it could likely pass the 5 percent threshold once campaign resources are expended. Renaissance doesn’t have the public support to win seats on the party-list ballot, but will win seats in districts in the east and south. Thus, with Ukrop winning 5 percent and a handful of districts in western Ukraine, it could get nineteen MPs. Additionally, the twenty-three current MPs in the Renaissance faction are likely to be reelected and the party can win other districts, particularly in Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, and Odesa. That gives Renaissance thirty-four seats in the next parliament; overall, Kolomoyskyi could directly influence fifty-three deputies.

Opposition Bloc: The party still has a label which sells in the east, but it is involved in a power struggle between its two financial sponsors, Rinat Akhmetov and Serhiy Livochkin. As a result, the Opposition Bloc is missing opportunities to capitalize on the government’s mistakes. Current polls put it at 7 percent, but with mobilization of its electorate in the east, the party could surpass its 9 percent mark from 2014 and rise to 12 percent. In addition, eleven independently-elected MPs from 2014 joined the faction and are likely to win reelection, along with other party candidates who will dominate Donetsk, Luhansk, and Zaporizhya. Therefore, with new elections, the Opposition Bloc could have approximately fifty-five MPs.

Radical Party: The political project of oligarch Dmytro Firtash is hovering around 4 percent in the polls, but is likely to surpass the barrier on election day. While the party won’t do as well as in 2014, it can still anticipate about sixteen MPs in the next parliament.

Svoboda: In 2012, Svoboda received 10 percent of the vote nationwide. In times of disenchantment with the government, Svoboda performs well; in times of solidarity with the government, Svoboda receives fewer votes. Currently, Svoboda has six MPs and is polling around 4 percent. By capitalizing on many Ukrainians’ sense that Euromaidan principles have been betrayed, Svoboda could get 5 percent, and could win a dozen districts in the west, particularly in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, and Khmelnytskiy, where Svoboda mayoral candidates won last year. Including their support in Lviv, Svoboda could elect twenty-six MPs in new elections.

If the elections were held today, the composition of parliament could be as shown:

This new parliament would be highly fractured and even less cohesive than the current one. To form a governing coalition, the President would need the votes of his faction, plus at least four others to form a government. In short, new parliamentary elections would create greater instability and should be avoided.

Brian Mefford is a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. He is Kyiv-based business and political consultant. You can read the full article on his blog here.

Image: Ukrainian former Prime Minister and leader of Batkivshchyna (Fatherland) party Yulia Tymoshenko attends a parliament session in Kyiv, Ukraine, February 16, 2016. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich